It started with an idea—the idea of reviewing, at long last, Sophia in Exile, Michael Martin’s latest book on Sophiology, a work shimmering with Christian beauty—alongside terrifying insight into the materialistic roots of our increasingly totalitarian technocracy that few grasp as Martin does.

But before that idea could turn into reality, something happened. Rather, many things happened—or even a mighty complex of interrelated events happened, some which remain too intimate and personal to enter into here (although I can say the sudden death of the late, great Michael Frensch played a part).

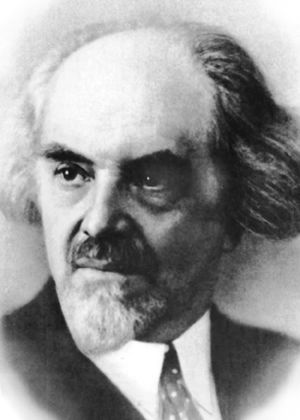

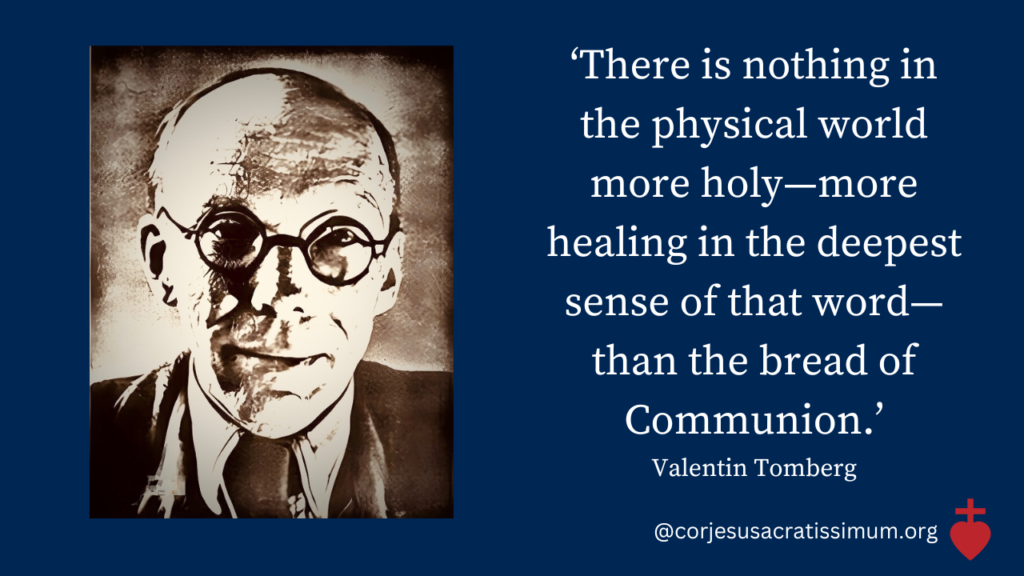

Suffice it to say these processes, both exterior and interior, relate to the legacy of Valentin Tomberg, as well as what I consider central to my life’s work—a core that entails seeking ways forward for the West, a West now, menaced in so many ways at once.

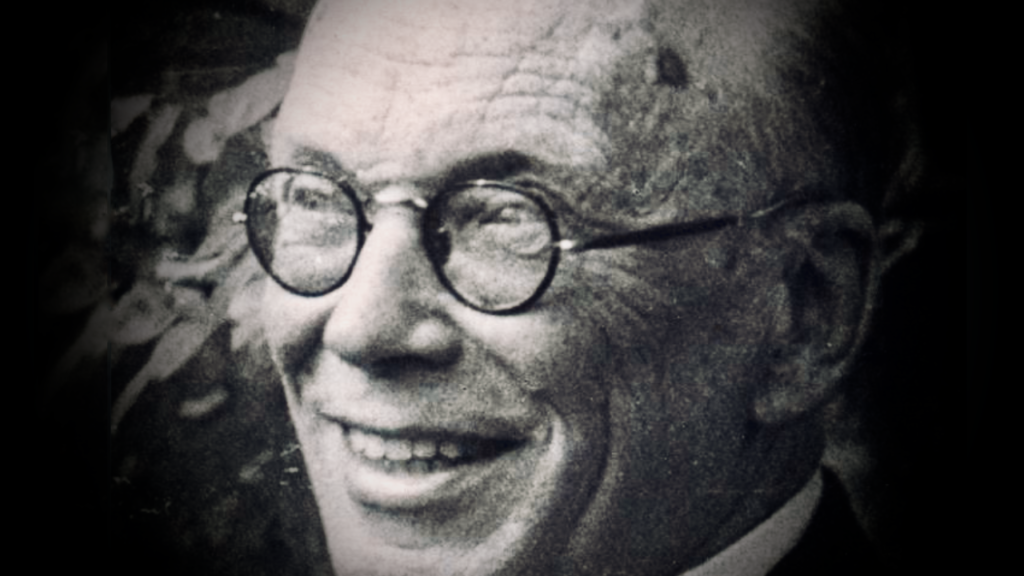

Now, Michael Martin also seeks to scry a way forward for the West, as Tomberg did before him, Tomberg who has influenced us both profoundly. Yes, Tomberg, Martin and myself all thirst for answers to the crisis of materialism. That notion is central to this present essay.

At any rate, dear Lector, after these partly-disclosed processes I still mean to write in depth regarding Sophia in Exile. For Sophia in Exile has so much to offer as I scry . . .

But is this a review? In part, yes—but only in part. I prefer to call it an engagement. I will engage Martin’s text but more as well, including his previous triumph Transfiguration. But along the way, we engage with other matters, too. These have to do, not surprisingly, with Tomberg, Sophiology and the technocratic nightmare whose roots in materialism Michael discloses with such acuity.

Michael, did I say? Yes, I know Michael a little and using his Christian name might seem more transparent and fitting in these circumstances, even if I know him almost entirely through internet exchanges. Michael has also been deeply supportive of my three books, for which I can never thank him enough. Another bond: we are both authors published by Angelico Press, whose books are all indebted to Valentin Tomberg.

Despite these bonds, I retain literary convention, saying ‘Martin’. For my belief in the man and his work goes far deeper than any personal connections.

Indeed, I have long praised Martin’s work with Tomberg’s legacy as superior to anything else I know—at least anything from the Anglosphere. (For the late German Michael Frensch most deeply impressed me in this regard too.)

This is significant as much as I am convinced Tomberg’s legacy is important . . . important to the West, now drowning in materialism.

It is crucial, then, that his legacy be understood properly.

This, too, forms part of the processes behind this long piece and we turn to the matter of Tomberg’s much-misunderstood legacy later on.

Right now, my point is that all this renders hope for ‘objectively’ reviewing Sophia in Exile somewhat dubious.

Nevertheless, I know Martin best through his books. My mail from him has not been extensive. By contrast, I have read Transfiguration close to four times now. Sophia in Exile I have read twice. This is unusual for me. That is part of my intimate process too: his books, books all to do with the crisis of the West, haunt me.

It is these two last books we mainly focus on here. Indeed, much of me wishes I could focus solely on these.

A Profound Difference

But in keeping with transparency, a word is needed regarding Martin’s other activities online: articles, videos, social media posts etc. For although I do not know these well—preferring books by far to cyberspace—I can no longer easily separate Martin the cybernaut (at least compared to me!) from Martin the author.

A chief thing here is Martin’s deep and pained disillusionment with Catholicism that increasingly manifests in his online activity (even if, again, I know relatively little of this).

Admittedly, Martin’s disillusionment was evident when Sophia in Exile appeared two years ago. Indeed, we find this at the very start of the text:

The tragic fire at Notre-Dame de Paris on 15 April 2019 [is] a fitting icon for a Church in distress, suffering from the weight of its own corruption, not least the ongoing sex scandals that fill us with shame and anger, evidence as they are of an ecclesial structure inured to the sufferings of its victims, and further complicated by the manner in which some of its most powerful leaders have continued to shield their own from scrutiny. These are symptoms of a deeper pathology. The hierarchy’s inept and milquetoasty response to the global pandemic that began in early 2020 only further betrays how indifference has become a cardinal virtue. How many millions died without receiving the last sacraments? How many more left the Church permanently because it was too hard for the hierarchy to live out the Gospel and too easy to play the political sycophant? Did Christ wait until lepers were no longer contagious to heal them?

Michael Martin, Sophia in Exile, p. xi-xii.

And online he now speaks of things like the ‘Sacramental Machine’. This term appears in a searing article here where Martin speaks of sexual abuse, Pope Francis, former Cardinal Theodore McCarrick and even how his own personal life was affected by matters hardly unrelated to the kind of horrors this appalling complex represents. This led to his abandoning Catholic practice and to his:

family . . . holding house church on Sundays, using an abbreviated version of the liturgy of the Book of Common Prayer (my doctorate is in Early Modern English Literature—in particular the Metaphysical Poets—so the BCP, based on the earlier Sarum Missal, is comfortable territory).

I read Martin’s piece with my heart open. Given its great personal pain, it would hardly be Christian not to. Moreover, men like McCarrick testify to something terribly, terribly wrong in the Church that goes far beyond them or their victims.

Would that more of us could feel this pain as acutely as Martin! Anyone judging the man should perhaps pray their own numb hearts might feel like his does.

Yet even while my heart goes out to Martin, even as his outraged heart commands my respect, I cannot join him in his conclusions regarding the Church or abandoning the Sacraments for the Book of Common Prayer. For while I can understand Martin’s love of the great English poetry within the book—he is a poet himself—I could never contemplate such an exchange, myself. Not for a second.

Put bluntly, I’d rather lose a limb than the Sacraments.

I need them like the air I breathe. Without them, I know I would be far more victim to unhappiness and despair—not to mention moral doziness—than I am.

Here I do not just mean the Catholic Mass but the Confession that cleanses my soul, and the Priestly Ordination that makes these miracles possible. I depend heart and soul on the entire Sevenfold Sacramental Miracle that that great English poet Thomas Cranmer dismantled on behalf of Tudor kings and their cronies, whilst bequeathing to posterity the Book of Common Prayer, precious to generations of Anglicans . . .

Here, then, is paradox and pain. The pain is, I think, not simply personal. For my experience of the Sacraments—not to mention Tomberg’s experience and that of countless Saints—means they constitute my hope for the planet.

Here is the serious difference I now have with Martin, stated plainly.

On this key, central thing, we go down different roads.

What can I say? Perhaps this: Whereas Martin cannot ignore (and should not ignore) the very real evil in the Catholic Church, I cannot ignore (and should not ignore) the very real good.

Now, several years ago, I wrote a book of imaginary dialogues called The Gentle Traditionalist. A brief extract may illustrate my meaning here:

GT: . . . the material good alone [done by the Church] is incalculable. Still, one shouldn’t be too materialistic here.

GPL: Materialistic? I’m not with you…

GT: Well, these days, there’s a danger of only seeing the material side of things. All the feeding, medical attention, harbouring the homeless, etc. Those used to be called the Corporal Works of Mercy. And, obviously, they’re tremendously important. However, I didn’t even mention the Spiritual Works of Mercy. Like praying for the living and the dead. Naturally, the greatest act of mercy is the Holy Mass. I said there were four hundred thousand priests on the planet. The majority of them say Mass at least once every day. Hundreds of thousands of times a day then, His Body and Blood are given to the world. The graces that flow from that are inconceivable. They completely dwarf anything else the Church does for people in terms of healing and feeding their bodies.

Roger Buck, The Gentle Traditionalist, p 120.

Much more could be said of this. But we are concerned with Martin, Tomberg and Sophiology here, not apologetics for the Church, although care for the Church certainly factors in the complex processes that birthed this piece. But it is only one factor in a bigger picture.

This bigger picture also informs my recent videos and articles regarding Valentin Tomberg and the fate of the West —efforts born from many concerns, but including certainly this one: that Tomberg’s understanding of the Catholic Church and Her Sacraments is being lost. Or it is even being obscured by some (though not by Martin, I hasten to add.)

Haunted by Martin’s Star

Despite the pain and gravity in these last lines, Martin offers me real hope, understanding, heart. When I say his books—above all his books—haunt me, I mean it.

I stare out into this sterile, technocratic ‘culture’ and Martin gives me insight, Christian insight, that few other contemporary Christian thinkers could. Let us listen to Martin on how the technocracy obscures the wisdom and glory of God in creation, for which, as we shall see, Martin uses the word sophianic. (And note: here as elsewhere we take the liberty of breaking up longer paragraphs into shorter ones for better comprehension from a screen.)

Not … every phenomenon has an equal potential to disclose the sophianic, or that we are at all times awake to the proper disposition to perceive it.

Works written corporately—as in advertising or governmental or business writing—do not seem capable of disclosing the sophianic in anything like the way that is possible (though certainly not assured) in poetry and other literary works …

This is due in part to the grasping intentionality characteristic of the “creative teams” involved in marketing: … the will and the ego insert themselves into the process by way of conquest. Likewise, liturgical forms, especially those that try to habituate themselves to the supposed tastes of a congregation (really, to be honest, an audience), may move the feeling but without disclosing anything sophianic.

Such are rhetorical moves, rank manipulation, which, at best, are simulacra of the sophianic. Indeed, an ultimately pornographic quality inhabits these desires to influence: they titillate with a promise of erotic satisfaction, but ultimately fail to create an opening into the beautiful. But they open into something. [Italics mine]

What, then, of manufactured or otherwise manipulated objects?… Can an artificial intelligence (AI), for instance, open to transcendence? What happens when we attempt [to truly perceive] those afflicted with gender dysphoria and who have reached the point where they turn to medical interventions to “change” their gender? Do we discover that these, too, are rhetorical moves having more to do with marketing than ontology? Or do we find something else? We certainly find a human person in a state of suffering. But, other than this, what is disclosed?

And when this rhetorical gesture becomes ideology (or fashion), as, for example, when children are given hormone blockers to delay the onset of puberty while they (and/or their parents) try to decide what gender they are, what then? What can be disclosed?

Similarly, are not GMO foods quite literally other than they appear? Are they not simulacra? Are not fields sprayed with glyphosate images of thanatos rather than of zoë? Are “three-parent babies,” surrogacy, in vitro fertilization, and other intrusions into the realm of human fertility not only marvels of scientific ingenuity but also of manufacturing genius?

Natural processes are increasingly “liberated” from nature; and, as they are, are they not more and more rendered products in need of government regulation and corporate protection and, thereby, means of control?

This encroaching and, in the main, uninterrogated acceptance of “technological reproduction” in all of its forms delineates a movement away from Sophia and her illumination of the united natural and supernatural realms …

When we can no longer differentiate between the Real and the simulacra, we have already compromised our connection to the spiritual in the universe, to God by way of Sophia. And when differentiating between the Real and the simulacra invites ridicule, hostility, and ostracization, we can then be sure that we have entered the realm of the demonic… that “our struggle is not against flesh and blood, but against the rulers, against the authorities, against the powers of this dark world and against the spiritual forces of evil in the heavenly realms” (Ephesians 6:12).

[We have become] convinced that spiritual forces, of any kind, do not exist, and that science and technology hold the keys to prosperity, health, and happiness … We … are imprisoned and isolated from the Real.

Michael Martin, Transfiguration p. 109-111.

Much might be said about these lines that disclose such acute understanding of the technocratic hell we enter. But the theme of this piece is not so much the descent into hell, but Martin’s Sophiological response to it, as well as my own response—and as we shall come to later, Valentin Tomberg’s response.

For now I offer it mainly for its indicators in terms of why Martin’s books haunt me, whatever (profound) differences I now have with the man. But there is more: his books are also written with real beauty: Martin the poet clearly informs his prose. They are likewise informed by natural, earthy outlook that obviously owes to his own original inspiration, but also the fact he is a biodynamic farmer, working with the agricultural impulses of Rudolf Steiner.

He does not just talk the talk against technocracy, he walks a different road. I imagine his farm, were I ever to see it, might well take my breath away . . .

Pondering Martin’s path, I cannot help but recall Tomberg’s exhortation regarding the Mages from the Orient who followed the Star to the Christ Child:

Those who follow the “star” must learn a lesson once and for all: not to consult Herod and the “chief priests and scribes of the people” at Jerusalem, but to follow the “star” that they have seen “in the East” and which “goes before them”, without seeking for indications and confirmation on the part of Herod and his people. The gleam of the “star” and the effort to understand its message ought to suffice.

Because Herod, representing the anti-revelatory force and principle, is also eternal. The time of Christmas is not that of the nativity of the Child alone; it is also the time of the massacre of the children of Bethlehem —the time where autonomous intelligence is driven to kill, i.e. to strangle and push back into the unconscious, all the tender flowers of spirituality which threaten the absolute autonomy arrogated to itself by intelligence.

Anonymous (Valentin Tomberg) Meditations on the Tarot, p. 533-34.

What can I say? Tomberg’s warning not to seek ‘confirmation on the part of Herod and his people’ is serious. For Tomberg, the world, drowning in materialism, will not be saved by kowtowing to Herod and his people.

Moreover, studying Martin over years now, I see a long, arduous trek through the desert following the Star, firmly refusing ‘confirmation on the part of Herod and his people’. For those who have not savoured the man’s efforts, this should become clearer as we proceed.

Right now, I just note these efforts are also indebted to sometimes idiosyncratic Christian authors, including the aforementioned Steiner, Tomberg, the English Metaphysical poets and of course the Russian Orthodox thinkers, priests and theologians who begat Sophiology.

What is Sophiology?

But to engage Martin’s profound Christian response to a de-Christianised world, some understanding of Sophiology is important. Yet, alas, as Martin himself admits:

Sophiology is notoriously difficult to encapsulate into an elevator conversation. Even for me.

Michael Martin, Transfiguration p. 4.

Helpfully, he continues:

Briefly (very briefly), there are essentially two manifestations of sophiology.

One manifestation arrives as the product of a mystical experience with a figure identified with the Sophia (Hokmah in Hebrew) of the Old Testament (particularly in Proverbs 8 and 9) . . . As the book of Wisdom affirms of Sophia, “She is a breath of the might of God and a pure emanation of the glory of the Almighty; therefore nothing defiled can enter into her” (7:25).

Michael Martin, Transfiguration p. 25.

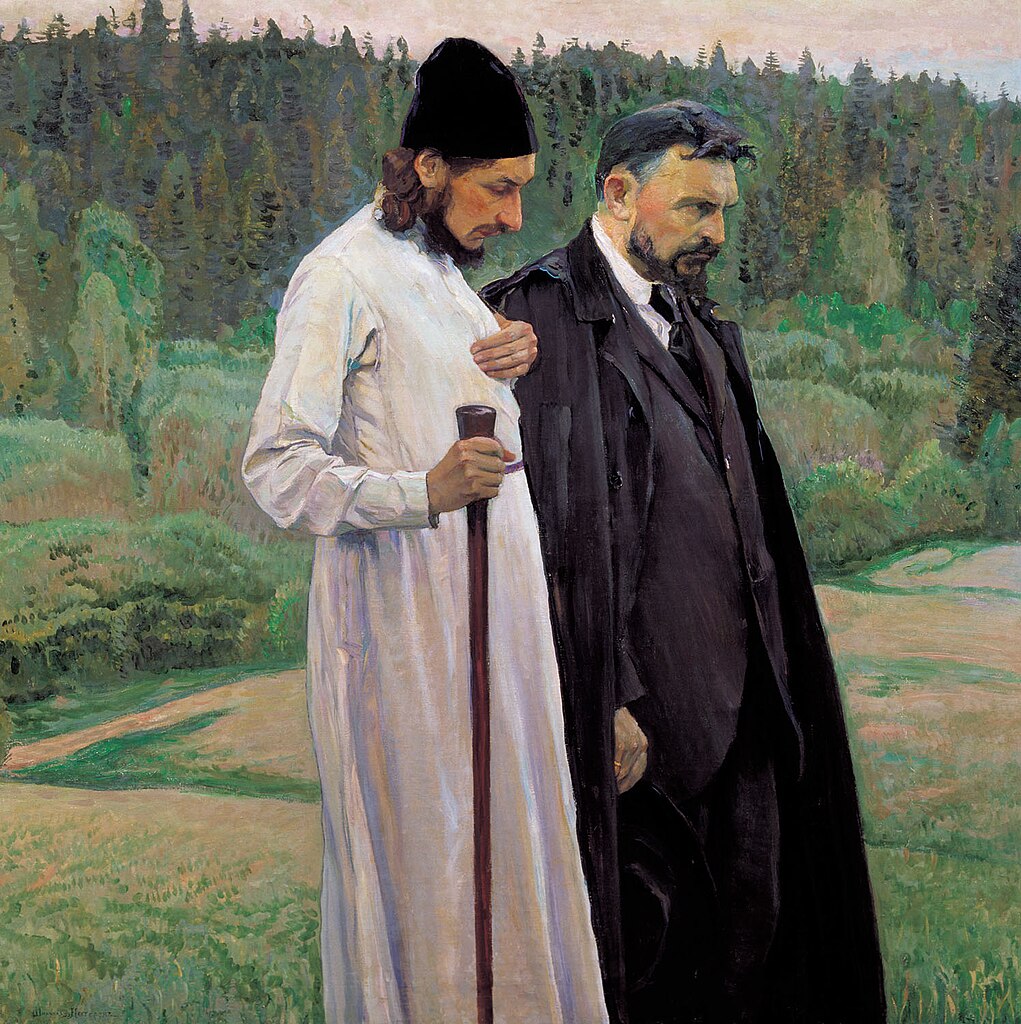

The mystical experience Martin alludes to is most recognisably that of Russian Solovyov (who perhaps converted to Catholicism before he died). But others might be mentioned including the Russian Catholic convert Valentin Tomberg.

Be that as it may, we are more concerned here (as Martin is in his books) with the second manifestation of Sophiology. This, it seems to me, has much to do with these words from the Gospel according to Matthew:

The eye is the lamp of the body. If your eyes are healthy, your whole body will be full of light. But if your eyes are unhealthy, your whole body will be full of darkness.

Matthew, 6.22-23.

It also has to do with, as noted earlier, God’s glory and wisdom revealed through Creation. But let us listen to Martin himself in some dense paragraphs which, again, we break into shorter units that may help contemplative reading from a screen:

The other manifestation resides in the philosophical/theological intuition that the Wisdom of God is integral to our experiences of the Truth, Beauty, and Goodness of the Creation—experiences that become palpable due to the reciprocal disclosure characteristic of contemplative engagement with phenomena.

There is an almost obvious Marian dimension to such disclosure: in the way that the Virgin Mary made God palpable to the flesh in Jesus, so the Virgin Sophia makes God palpable in creation and in created works. In a divine reciprocity, the Virgin Mary, the Sophia creata, reveals the full mystery of God’s Incarnation; whereas God’s Wisdom, the Sophia increata, reveals the parousia, or presence of God.

These experienced phenomena can be aesthetic, scientific, theological, philosophical, or liturgical, and they reveal the supernatural dimensions of Things.

Clearly, this engagement intrudes into realms typically ascribed to mysticism. And, indeed, in this regard Sophia occupies a metaxu between science, art, and the religious. Art often evinces resonances with mysticism. Why should science be any different?

Sergei Bulgakov, arguably the most important sophiologist of the twentieth century, reads Sophia “as the soul of the world…the center of all creation.” . . .

Bulgakov’s Sophia represents not a romantic escape from the sometimes cruel and unpleasant realities of nature—he knows creation is fallen—but he nevertheless recognizes the glory of the Lord (Sophia) coextensive with fallen nature.

Attentiveness to the sophianic nature of the world is central not only to religion, science, and art for Bulgakov; it is also crucial to a truly human economy: “The purpose of economic activity is to defend and to spread the seeds of life, to resurrect nature. This is the action of Sophia on the universe in an effort to restore it to being in Truth.”

Without a sophic awareness, argues Bulgakov, we are left with an impoverished set of tools: “Ratio, scientific or theoretical reason, emerges from the ruins of the sophic; it becomes the lantern with which we seek the Logos in the nocturnal darkness.”

The emphasis on “ratio, scientific or theoretical reason” characterizes the sciences . . . and also defines the manner in which the sciences are taught in nominally Catholic schools, whether K–12, college, or university.

The Logos will not be found with the tools now employed by science. Catholic scientists—if they are, in fact, Catholic scientists and not simply scientists who go to Mass—will require tools proper to such an investigation in order to truly disclose the glory of God participating in all things . . .

Sophiology, obviously, is not a way of perceiving that a majority of the current mainstream scientific community will welcome as valid for a number of reasons.

Michael Martin, Transfiguration p. 25-27

This is a rich passage, rewarding careful study. We cannot address all Martin evokes here. Yet the last line is key: Sophiology entails a way of perceiving exiled by our mainstream scientific community born of the Enlightenment. For that community is hardly fond of experience born of ‘disclosure characteristic of contemplative engagement with phenomena’.

The Impoverishment of Catholic ‘Culture’

Alas, many other Children of the Enlightenment are hardly fond of it either! This includes, Martin argues (accurately, I think) a vast number of Catholics who may never realise they actually are Children of the Enlightenment!

Here is why Martin speaks with pain—yet also, I think, a prophetic rage that many Catholic educational institutions are but ‘nominally Catholic’. For this, he references his own experiences, whether growing up in Catholic schools in America or later as English professor at a Catholic college in Michigan.

Insights from this experience of Catholic education along with heartfelt pain and anger inform much that Martin writes, including the two books we engage with here: Sophia in Exile and Transfiguration.

Essentially, Martin is saying so much Catholic education—at least in America—is not truly Catholic in that it hardly takes the Supernatural seriously (with the exception of the Mass on Sunday and even that is often only lip-service). No, this nominally Catholic education both participates in and propagates the Enlightenment of Seventeenth Century Rationalism.

That Rationalism, he contends, slowly murders us. We are deluged by it in the mainstream secular culture. Ought we not expect something better in Catholic culture? Do we not deserve something better?!

My questions are rhetorical, of course. And I agree with Martin that the ‘milquetoasty’ Catholicism he sees (and of course worse than ‘milquetoasty’) reeks of capitulation to the Enlightenment.

This matters—on many fronts at once.

Among these is the truth that, as Martin astutely observes, people turn away from the Church for precisely this reason:

My claim is that the souls who have felt such a profound attraction to the Occult Revival of the nineteenth century, to Blavatskian Theosophy and Anthroposophy, to Guenonian metaphysics, to the New Age, neo-paganism, and other such movements are driven by a desire for the sacred they find unavailable in mainstream forums of religious expression, which are all too often compromised by worldly concerns and politics, if not stomach-turning scandal.

Michael Martin, Sophia in Exile, p. 89.

That said, my experience of Catholicism differs greatly to Martin’s. I do not share his particularly, perhaps even peculiarly, American experience of Catholic institutions. As I shall come to, my Catholicism is formed by Europe, above all Ireland, which still takes my breath away—even if many of our present Irish bishops seem just as much milquetoast. This difference of experience is key to much I say later.

Foreword for Monarchy by Roger Buck

A Heart in Pain

More importantly, though (far more importantly) Martin is right to raise the issues he does.

Too much Catholic thought is held hostage to Enlightenment Rationalism. We are unconscious prisoners of a worldview that interprets reality in soul-destroying materialistic categories. People are seeking out neo-paganism and New Age-ism precisely because of this.

Obviously, this is not just a problem for American K-12 Catholic schools and colleges. This worldview is a problem for nearly all education in the West. And it lies at the root of today’s growing technocratic totalitarianism.

Here is one reason I love Martin’s work. He reveals this in a way few other contemporary Catholic thinkers do. He highlights the links between our abstract, sterile, uniform ‘culture’ and the abstract, sterile, uniform Enlightenment modes of ‘thinking’ we nearly all imbibed since Kindergarten (and often earlier in a world with tiny infants placed in front of TV sets . . .).

Martin’s thinking then is important. But his heart—in searing pain at what he sees—renders further witness. For seeing such naked pain at Catholic culture, we may be be perforced to ask ‘Am I in pain like this? And if not, why not? Am I, perhaps, as Pink Floyd sang, comfortably numb?’

Certainly, I felt compelled to ask that, myself. For despite all her defects, despite the real trauma her all-too-human members have inflicted on innocents, I do not despair of the Church. She remains my life’s hope and joy. The source of the greatest joy I have in this world. Like nothing else I ever found before I entered her . . .

But reading Martin’s growing disillusionment with the Church forced me to ask: am I numb to the horrors he sees? Is something wrong with me when a man I respect as much as him feels so very differently to me? Have I, in seeking answers to the crisis of our times and following the Star, missed something important?

At any rate, my respect for Martin’s work is such that he compelled me to question myself like this. For authors and thinkers, there are few greater accolades than this.

Verificationist Reductionism: A World Tragedy

Be that as it may, the horrors Martin sees are hardly limited to Catholic institutions. No, his books address the growing technocratic nightmare all around us.

They contain original insight concerning Capitalism, the Scientific and Medical Establishments, Propaganda, and —drawing on both his experiences as an English professor and biodynamic farmer—the threat to the Humanities in the American university as well as the threat of American Big Agriculture. Given how these American trends tend to spread through the Anglosphere and even reach into continental Europe, they make chilling reading for me in Ireland.

That said, as Martin knows as well as I, the problem is not any one nation or culture, nor plutocrats, nor any one class of people or even economics system. The problem lies in the way materialistic, utilitarian, mechanical categories, concepts and cognition are prioritised over all other ways of seeing.

This is what Sophiology would correct. For it entails a different mode of seeing the world.

What is this cognition? What Martin is getting at is something not easily grasped by a society obsessed by data and statistics. Because it abhors superficiality and demands effort. Yet it involves something natural not only to the Russian Sophiologists, but also great poets, mystics, contemplatives of all traditions and even little children in the sense of entering the Kingdom (Matt. 18.3).

In the course of his books Martin draws insight from all these—i.e. from Solovyov to Tomberg, Steiner, Goethe and his own brood of nine kids—to demonstrate the elusive forms of awareness and cognition exiled by the Enlightenment. All Martin’s writing turns around this sophic awareness whose nature is not easily appreciated in a shallow age. But to illustrate, we start with some moving lines from the first chapter of Transfiguration:

How we observe phenomena possesses ontological, epistemological, and even physiological ramifications of which we should be vigilantly mindful. Observation, as Werner Heisenberg and Niels Bohr were among the first to acknowledge, is never scientifically neutral. And I would add that neither can it ever be morally neutral.

Our sciences, though, are rather enthralled to the daemonia of abstraction, dogmatics, and the faerie glamor of electronic and technological mediation. Recently, for example, I asked the science division at my own small liberal arts Catholic college if I might borrow a few prisms for a demonstration on light and colour in a theology course. The science faculty didn’t know if the college had any. . . . I am sure that students learn about optics in their physics classes. Or, rather, I am sure they are told about or read about optics in their physics classes. . . . But I am not at all convinced that they experience optics in their physics classes. . . .

The enthrallment of the sciences to the technological and their immunity (or so it would seem) from ultimate meaning and metaphysics clearly have something to do with federal and corporate STEM dollars flooding into research departments. The lure of profit and power.

But it has even more to do, I think, with their estrangement from philosophy and theology. [Italics mine] As such, then, science puts itself in danger of becoming a technological enterprise rather than a human one, an enterprise of power devoid of ethics, utilitarian and as cold and inhuman as the emptiness of outer space, as warm and reassuring as the voice of a robocall. Fear is one of its tools. Entertainment another. Efficiency, yet another. Love never figures into the equation. What would happen if it did? . . .

The cosmology of scientific materialism . . . lies open to investigation and interpretation, though only within the proscriptions first outlined by Bacon and Descartes—that such phenomena and their effects are testable, verifiable, reproducible, and predictive: a thoroughly verificationist paradigm. [My Italics]

Love, for instance, though it has a place in religious cosmologies, has no role in this one. Should it? Or, rather, shouldn’t it?

The mainstream of the scientific community, at least as it now exists, would say no. This is a problem. At best, evolutionary biology, evolutionary psychology, or neuroscience would describe love in terms of the biological imperative, partner selection, courtship displays, chemical reactions— but this is simply a “me Tarzan, you Jane” understanding of love.

Michael Martin, Transfiguration, p. 15-17.

Yes, love, which should be at the centre of all our aspiration is marginalised by the standards of what:

Goethe . . . called the “gloomy empirical-mechanical-dogmatic torture chamber” that science had become in the wake of Bacon, Descartes, and Newton.

Michael Martin, Sophia in Exile, p 88.

We continue to be obsequious to these standards or worse addicted to them, as though nothing could be true and worthy that is not capable of being reduced to data.

Sophia—Wisdom—is thereby exiled.

Things go from bad to worse with the big, big bucks added to the mix. As Martin writes:

It is no secret that science in our time has, for some, become a belief system, and people with very limited scientific knowledge proclaim that they “believe in science.” And even though the corporate investments in scientific “research” have been shown to often compromise not only science but also the health and well-being of millions—to a degree that should certainly undermine the absolute trust some place in the scientific enterprise—our culture persists in its valorization of what “the research shows.” This is superstition writ large.

Michael Martin, Sophia in Exile, p 8

Sophia in Exile

But, obviously, Martin locates the roots of Sophia’s exile much further back in time than the current reign of corporate technocracy:

The beauty of the Renaissance was that it allowed a vision of being human full of hope, illuminated by divinity. This despite the ravages of plague, war, conflict, and the usual tragedies attendant upon our condition. The Reformation destroyed all (or almost all) of that, and pessimism, materialism, and utilitarianism followed in its wake. The universe was at last disenchanted.

Michael Martin, Sophia in Exile, p 94.

The Reformation, via Hobbes, Descartes and Locke, led to the Enlightenment and the Children of the Enlightenment continued to build a grey, joyless world of despair and reductionism.

Beginning with Freud, whose pessimism infected all of his ideas, however brilliant, the twentieth century witnessed a steady and almost absolute dissolution of an integral understanding of marriage. This is primarily attributable to the almost pathological attention paid to sex and sexuality which jettisoned marriage to an ancillary position in the Positivist Grand Scheme of Things. The Sexual Revolution, indeed, celebrated sexuality as a right and denigrated marriage as an “institution,” in the way that mental hospitals and prisons are institutions, and not as a paradigmatic structure of human flourishing encompassing all peoples of all nations throughout all of history. . . .

Marriage began more and more to be seen as anachronistic to a liberated and enlightened age. This trend was rendered all the more astonishing when marriage was asserted as a right to which gay and lesbian couples were entitled—a right to which no gay man or lesbian woman ever aspired until the concept’s popularization in the early decades of the twenty-first century. . . . Marriage in the cultural imaginary has been almost entirely secularized, with no spiritual or metaphysical correlative to be found.

Michael Martin, Sophia in Exile, p. 55.

Amen.

But the centuries of reducing marriage from a Sacrament to a legal system is, of course, paralleled by countless other instances of desacralisation. Thus, Valentin Tomberg believed Vatican II followed the same terrible trajectory which led:

to degeneration, to exhaustion, and to death (hades) – the “way of the world”. This failure to guard the threshold of the portal opening up to the “way of the world . . . is nothing else and can be nothing else but the way to death

Valentin Tomberg, Covenant of the Heart, p. 111.

Not only has the current climate in the Vatican turbocharged this trajectory, but I cannot resist adding a rare exchange of tweets between Martin and myself which, at this point, seems germane. Michael tweeted:

Not a traddie by any means, but I have to say that the aesthetics of the Novus Ordo are pretty much the equivalent of a liturgical strip mall.

Most unusually for me, I tweeted back:

Sophia in Exile. My wife who has long been more naturally Sophiological and more “Traddie” than me à la fois (I needed her to achieve the latter) might say: HE is in the New Mass. SHE is stripped away . . .

Yes. Putting aside my wife’s role in opening me to both tradition and Sophiology, there can be no doubt Christ remains present in the new Mass. Inwardly, its essence remains unspeakably holy.

But that holiness is now expertly hidden as its aesthetics (and much else besides) were subjugated to the same corrosive trajectories of the Reformation and Enlightenment. Beauty, soul, are banished. Martin, my wife and I see that in common, I think.

That said, Martin, it must be acknowledged, takes Sophia’s exile much further back than simply the Reformation. Controversially, he proceeds back to the Church fathers, following the Russian thinker’s Nikolai Berdyaev’s lead in pointing to a:

Christian culture, engineered by celibates and monastics, who through a compromised anthropology long ago disfigured the nuptial image into one that privileged their own social contexts and power.

Michael Martin, Sophia in Exile, p 51.

Assenting to Berdyaev, Martin asserts:

Thus began the long, slow decline to Freud, the Sexual Revolution, and Theodore McCarrick.

Michael Martin, Sophia in Exile, p 94.

Here I cannot follow Berdyaev and Martin. Now, I have little problem believing that certain Church fathers did too easily equate the world, the flesh and the devil.

But to see this as the start of grave world problems remains open to question. Why start with Patristics in speaking of sexual pathology? Why not Platonism? Why not earlier still with the dualistic religions of Persia and India?

I am no expert in Zorastrianism, Buddhism and Hinduism, but I know enough of them to see the same problems Martin locates in the early Church. And when I was young, I was devoted to Gandhi, who was devoted to the Gita and Gandhi certainly had his share of sexual pathology. (Great soul that he undoubtedly was.)

Personally, I would rather locate such pathologies in the Fall itself, rather than Christianity per se. And with many critics of Christianity, I fear there is insufficient acknowledgement that the Fall disfigured all human institutions and not simply the Church. A point I return to . . .

The Sophiological Remedy for Modernity

At any rate, we have largely been concerned here with Sophia’s exile: What Sophiology is not. Some may still struggle to grasp just what Sophiology actually is. And perhaps ultimately that is because what Martin means is not something to be pinned down in precise terms by analysts and statisticians, who are not Sophiologists, precisely because they are habituated to . . . pinning things down.

Rather, Sophiology aspires to a contemplative engagement with what is real: neither reductive and specialised categories, nor fragments detached from the whole. This vision then is holographic, thus integrated with philosophy, theology and metaphysics. This means it is not morally neutral. It entails, then, rejecting what Tomberg describes here:

Many thinkers and scientists want to think “without the heart” in order to be objective —which is an illusion, because one can in no way think without the heart, the heart being the activating principle of thought; what one can do is to think with a humble and warm heart instead of with a pretentious and cold heart.

Anonymous (Valentin Tomberg) Meditations on the Tarot, p. 111.

And yes, it resists the pharisaic efforts of Herod and his people:

to strangle and push back into the unconscious, all the tender flowers of spirituality which threaten the absolute autonomy arrogated to itself by intelligence.

Anonymous (Valentin Tomberg) Meditations on the Tarot, p. 533-34.

But Sophiology is not simply a negation. And as Martin writes:

Sophiology, it is my contention, is above all something one does, a way of being. It is not a grand theory, a beautiful intellectual construction. No. Sophiology is an entrance into life . . .

We live in exile from the Divine and the Creation. As the pandemic and the ever-increasing totalization of the technocracy have shown, we are also in exile from each other, and, ultimately, from ourselves. This is an untenable situation and one which, if left unchecked, will have disastrous repercussions, many of which are deep into their implementation stages. The antidote to such a situation, as I argue in these pages, lies in reorienting ourselves to the Real . . .

In essence, what Sophiology offers is a regeneration of life by an engagement with what is Real. And this regeneration is conditioned by learning how to see. [My italics]

Love is integral to this seeing, as both agapeic opening and as erotic longing. This integral seeing in not characterized by . . . acquisitiveness or desire to possess, so much as it is a product of the subject’s entrance into a loving disposition to that which shines through the world.

Michael Martin, Sophia in Exile, p. xiii-ix.

Moreover, the subject’s capacity for loving, contemplative engagement may lead to more than just deepened cognition. For such naturally fosters genuine inspiration and creativity and Sophia in Exile has much to say in terms of the creative act in art and poetry:

What is it we do when we create? In so-called primitive societies, and through the classical era, poetic creation—and thereby artistic creation generally—was associated with prophecy, a kind of divine madness in which the creator’s self was instrumental to the divinity speaking through him or her. The poet merely functioned as a conduit, a pipe, for the god in question. Inspiration — literally a breathing in of the god—… is essentially an involuntary act… No doubt, this has something to do with the impossibility of adequately explaining artistic inspiration, a feat no one has yet been able to achieve.

Because human creativity (ubiquitous as it is) defies explanation, recourse to religious language offers what may be the only rhetorical ecosystem up to the task . . . The truly creative act, in whichever domain, accesses and partakes of this divine life, full of mystery and wonder.

Michael Martin, Sophia in Exile, p. 85.

Human creativity is participation in God’ Martin writes elsewhere, quoting Berdyaev

“It wills another world, it continues the work of creation.” As such, true creativity—a creativity touched by the mystery of redemption—becomes theurgy.

Michael Martin, Transfiguration p. 39.

Now, I hesitate to say much more on Sophiology. I am not qualified. I have not followed this same Sophianic star through the wasteland that Martin has. Indeed, what I know of Sophiology owes largely to him, but also Tomberg (and a little Solovyov). Thanks to them, however, I am convinced in the Sophiological Remedy for Enlightenment poison.

Here, as Martin says, lies real hope for the world.

Both/And: Valentin Tomberg and the Fate of the West

Here is my hope, too, as well as part of our inheritance from Tomberg. And it is time we to turn to Tomberg now, as promised from the outset.

For anyone who has dwelt long on Tomberg can clearly see, Martin’s real debt not just to the Russian Orthodox Sophiologists, but the Russian Catholic one as well. Of course, Tomberg, in turn, was indebted to his Russian predecessors too, most obviously Solovyov—as he was likewise indebted to the Hermeticists—including not simply the French Péladan and Papus, but also the German Steiner and Goethe before him. (Careful reading of his magnum opus reveals he oten grouped these French and German Christian streams together.)

There is a vein of gold here in terms of profound awareness, seeing the depths of the world beyond Enlightenment Rationalism. Tomberg saw this gold, even if he also repeatedly warned of real dross and real danger in the case of the Hermeticists. Danger of charlatanry, psychological grandiosity, destruction of tradition and much else much that is natural and good.

He returns to this theme again and again and again throughout Meditations on the Tarot! Alas, his sustained, repeated warnings often seem to fall on deaf ears . . .

Despite this, I am convinced, like Martin and Tomberg, that this vein of gold—sometimes Hermetic, sometimes Sophiological—is necessary to address the technological monsters born of Enlightenment tunnel vision. And Martin is right that the Church, too, is now dragged down by these monsters.

But Tomberg did not only stand for the Hermetic gold amidst the dross. He did not only stand for sophic awareness. He stressed the need for Catholic orthodoxy including dogma and hierarchy.

Saying that, we return to the mysterious complex of processes that give rise to this long piece. As I have intimated, these processes entail my responses to Martin’s work and path, but they concern far more as well (including other good people too). And ultimately my reason for writing has to do with something far bigger than personalities.

They concern, as I have said, scrying answers to the Crisis of the West, drawing on Tomberg answers to the Crisis of the West. This quest lies at the heart, in fact, of all my recent videos and articles on Tomberg.

And in this quest, undertaken over years, it becomes ever more clear that as much as Tomberg’s answers to the Crisis lay in the kind of sophiological awareness Martin so eloquently evokes, his answers went beyond this too.

Because, again, Tomberg was not simply sophiological and Hermetic! He was also dogmatic in the best sense of the word; he sought to honour and obey the Catholic Church; he steeped himself in the Sevenfold Sacramental Miracle of the Church, going to Mass and confessing his sins, over the course of his Catholic life. (And even before when, unusually for an Anthroposophist, he participated in the Russian Orthodox liturgy.)

Here the later Tomberg departed radically from Steiner (if not the Russian Sophiologists) who saw no need for the Church in the future and even castigated it. And whereas Steiner continually harkened to the future, as progressives tend to do, Tomberg also emphasised the need for continuity with the past, a living, growing tradition that neither sought mindless replication of old models, nor surgically chopped them off either. Likewise, Tomberg repeatedly calls us to be obedient sons of the Church, taking her dogmas and disciplines seriously.

This is because Tomberg prayed and worked, day and night, in the hope and belief that:

Now is the time for the Hermetic movement to make true Christian peace with the Church and to cease to be her semi-illegitimate child, leading a half-tolerated life more or less in the shadow of the Church —and to become eventually an adopted child, if not a recognised legitimate child.

Anonymous (Valentin Tomberg) Meditations on the Tarot, p. 189.

Yes, because for the mature Catholic Tomberg, hermetic awareness, probing the depths of the world, was needed—but by itself it was not enough. The Church was needed, too.

To be clear: Tomberg repeatedly stressed that the Church alone sufficed for individual salvation (cf. his Meditations p. 265).

But for society as a whole, ever more lost in materialism, Tomberg was clearly looking towards both the Church (as mother) and Hermeticism (as child).

Both/and.

‘Transformed in the Blood of the Lamb’

And if Tomberg now sought different answers to the Crisis of the West than he had in his Anthroposophical youth, it was obviously because something was different. Something had changed …

That change was both outer and inner. It involved, as we have related in several recent pieces here, Tomberg’s experience of World War II. This shattered his hopes that Anthroposophy could address the appalling state of global materialism. And in these broken dreams, he turned away from his former faith in Anthroposophical cognition to the Catholic Church, which he began to defend in terms shocking to Anthroposophists.

All this poses tough questions for those who care for Tomberg’s legacy. But, alas, as I have pointed out elsewhere, too often people have too easy answers to these questions. That is one reason Martin has long impressed me: he avoids such laziness.

Moreover, he clearly sees Tomberg’s change:

“[Tomberg’s] Catholic works were written by a different man, one transformed in the Blood of the Lamb.”

Michael Martin, The Submerged Reality, p. 193.

Yes Tomberg changed. Michael Frensch in Germany saw this clearly as well, though, alas, there are many who do not. This change manifested not only in renouncing Anthroposophy and conversion to Catholicism, but also in his call to Hermeticists to honour and support the Church.

Alas, Tomberg’s transformation, as I say, goes too often unrecognised. As I have said in recent pieces, I see real danger here. It is the danger of CONFLATING the later Catholic Tomberg with the earlier Anthroposophical one.

And conflating these, we cannot easily see the mature Tomberg’s call. We cannot see his call to ‘Both/And’. We cannot see his call to the Sacramental Miracle and the obedience it entails. Here Tomberg saw grave peril, which is why he wrote:

The Church is based on the three sacred vows—obedience, poverty and chastity—whilst we Hermeticists behave as pontiffs, without the sacraments and the discipline that this entails . . . We do not want to obey either religious or scientific discipline. 190

Anonymous (Valentin Tomberg) Meditations on the Tarot, p. 190.

A Digression on the Notion of a Universal Church

A little digression: Tomberg’s call to obey the Church is sometimes obscured these days by supposing he merely meant some sort of elusively vague ‘universal Church’. This is facile. It is obviously easy to ‘obey’ or ‘follow’ an ill-defined, insubstantial Church, which too easily becomes whatever one wants to ‘obey’ or ‘follow’. But Tomberg was not interested in easy answers.

No, what he meant by the Church clearly included dogma, discipline, hierarchy and Papal Infallibility.

This means the centralised, hierarchical Church that Tomberg praises and it definitely does not mean to include anything and everything people would like to imagine under the heading of a supposed universalism. Yes, Tomberg sees the good in every religion and he knows Christ came for us all:

the Master himself . . . loves everyone, Christians of all confession as well as all non-Christians.

Anonymous (Valentin Tomberg) Meditations on the Tarot, p. 282.

And there are further hopes in Tomberg’s work for a future Church that embraces all, with intriguing lines like this regarding the Church’s

universal operations, destined to serve the whole of mankind, and transcending space and time, i.e. the seven sacraments of the universal Church

Anonymous (Valentin Tomberg) Meditations on the Tarot, p. 65.

‘Destined’ though hardly means now.

Still less do such things mean Tomberg was conjuring up an all-embracing universalist Church ‘without the sacraments and the discipline that this entails’!

No. Tomberg repeatedly called for these seven sacraments (very much including confession of our sins), ecclesiastical discipline and he repeatedly critiques those who forego such, as when he writes of:

the Protestants, who have separated themselves from the stream of living tradition – the Church.

Valentin Tomberg, Covenant of the Heart, p. 165.

Moreover, when Tomberg does invoke the idea of a universal Church in the present day, there are lines in his books that clearly point to his equating it with Catholicism:

[T]he Catholic Church, being catholic or universal, cannot consider itself as a particular church among other particular churches, nor consider its dogmas as religious opinions among other religious opinions or confessions.

Anonymous (Valentin Tomberg) Meditations on the Tarot, p. 89.

This may not be easy for Hermeticists, but, again, Tomberg was not in the business of easy answers. He knew many would not find this easy, which is why just a few lines after this, we find a rejoinder (to possible objections to this and more that he has said).

Dogmatism? Yes, if one understands by “dogma” the certainty due to revelations of divine worth which prove fruitful and constructive, and due to the confirmation that they receive from reason and experience together. When one has certainty based on the concordance of divine revelation, divine-human operation, and human understanding, how can one act as if one did not have it? Is it truly necessary “to deny three times before the cock crows” in order to be accepted into the good company of “free spirits” and “non-dogmatics”?

Anonymous (Valentin Tomberg) Meditations on the Tarot, p. 89.

What can I say? Tomberg was not trying to shoehorn anything and everyone into an insubstantial, non-dogmatic, New Age-y carry-all bag.

Now, there are some who suppose my interpretation of Tomberg boils down to my ‘rigid’ Catholicism. The truth is I only adopted ‘rigid’ Catholicism, because Tomberg led me to it—after figuratively kicking and screaming for years on end. Because once I wanted a New Age-y universal Church myself. But I could no longer ignore the very texts others would seem to ignore and that fact, along with life-transforming experiences in France, dictated my becoming ‘rigid’ . . .

When We Conflate the Two Tombergs

Now, these distressing matters relate to the conflation invoked earlier, whereby the younger Anthroposophical Tomberg is confused with the older Tomberg who changed so profoundly, even saying that his transformation was so great he should bear a different name now.

For when we confuse the two Tombergs, it becomes easier to forget or ignore all the ‘rigid’ things the later Tomberg had to say about things like Roman centralisation, Protestants, Hermeticists refusing to obey, the sterility of Anthroposophy and suchlike . . .

This is important and I think Tomberg thought it important, too. It helps explain why he did not want his old Anthroposophical works republished. It also helps explain a striking thing in Meditations on the Tarot, one that occurs not only on the very first page of the book, but in the very first paragraph:

These meditations on the Major Arcana of the Tarot are Letters addressed to the Unknown Friend. The addressee in this instance is anyone who will read all of them and who thereby acquires definite knowledge, through the experience of meditative reading, about Christian Hermeticism. He will know also that the author of these Letters has said more about himself in these Letters than he would have been able to in any other way. No matter what other source he might have, he will know the author better through the Letters themselves. [Italics mine]

Anonymous (Valentin Tomberg) Meditations on the Tarot, p. xi

This is the fourth sentence of the book! And placing it in such an immediate and prominent position would seem to indicate Tomberg was concerned about his Magnum Opus being confused or conflated with his other work.

At any rate: this is what we witness in many quarters today: a tendency to conflate the older Tomberg with a younger version of himself, whose writings he regretted.

Cultural Disintegration and Planetary Pain

And this conflating tendency plays a part—but only part—of the mysterious complex of processes giving rise to this piece. But there is much more here not easily named: prayers, dreams (including some of the most profound of my life) Michael Frensch’s shocking, untimely death and, yes, my awareness of my differences from Martin’s journey, particularly since he dispensed with the Catholic Sacraments. (Even though, again, I hasten to say Martin does not belong to those conflating the two Tombergs! Clearly, he has engaged and dwelled with the Catholic Tomberg in depths of sophic contemplation . . .)

Yes, this piece turns on many things and, to be frank, some of them pain me. I do not think my pain is merely personal. Indeed, I think it may be more planetary than personal (as grandiloquent as that sounds). Because much is at stake here.

Modern despair or even attempted negation of the Catholic Church repeats the despair and attempted negation of many pained souls in the past: from Martin Luther to Rudolf Steiner. Indeed, it certainly includes the young Tomberg, as well.

But after World War Two, however, Tomberg clearly saw things differently. He obviously became severely critical of the Reformation, repeatedly criticising Luther, Calvin and their efforts. He saw it had led to cultural disintegration.

But at the same time, Tomberg was intensely aware of the evils of the Renaissance Papacy that gave rise to Luther’s outraged heart. For Tomberg, the reformers would have been right to be grieved and horrified by ecclesiastical evil—but the answer to that evil was neither revolt, nor destruction of tradition. Here is why Tomberg celebrated the Counter-Reformation, rather than the Protestant revolution:

The Counter Reformation . . . should not be understood as anti reformatory, but as a true reformation [Italics mine]. For the movement toward interiorization and spiritualization which arose then in the Church was indeed in a real sense reformation, and in no sense a process of outer revolt – destroying images and annihilating Church hierarchy, and doing away with spiritual orders and the three vows. A monastery, for instance, is not reformed by chasing out the monks, but by bringing in a more interiorized spiritual life-as was the case, for example, in the reformation of monastic life in the Carmelite Order proceeding from St. Teresa of Avila.

The so-called Counter Reformation and the so-called Reformation stand in the same relationship to one other as the spiritualization of monasteries stands in relation to their dissolution. The first was an impulse toward inner transformation; the second signified rebellion and “purge”. The one meant “evolution”, the other signified “revolution”. CoH 97

And in Meditations on the Tarot, Tomberg suggests Catholic saints such as St John off the Cross and St. Ignatius of Loyola were needed to atone for the sins of Luther and Calvin and the ‘tragic repercussions’ of their actions (cf. 395-6).

Enlightenment Monsters

What can I say? Tomberg was acutely aware of the evil in the Church that, of course, goes back to Judas Iscariot. But he repeatedly counselled against revolution and rebellion towards the Church, warning that such carries a high price indeed —as he writes in this highly sophiological passage:

Each revolution which has taken place in the West —that of the Reformation, the French revolution, the scientific revolution, the delirium of nationalism, the communist revolution —has advanced the process of ageing in the West, because each has signified a further distancing from the principle of the Virgin. In other words. Our Lady is Our Lady, and is not to be replaced with impunity either by the “goddess reason”, or by the “goddess biological evolution”, or by the “goddess economy”.

Anonymous (Valentin Tomberg) Meditations on the Tarot, p. 294.

Here then Tomberg speaks sophiologically about the very monsters Martin so acutely unveils: the idols of rationalism, scientism and Capitalism. Yet Tomberg warns (here and many places elsewhere) that revolution itself, beginning with the Protestant Reformation, gave rise to these monsters.

What can I say? Martin Luther responded to the evils in the Church of his time—with catastrophic results. Rudolf Steiner supported Luther’s revolution and many that followed it. But Tomberg saw catastrophic results in Anthroposophy, too, albeit on a much smaller scale. The young Tomberg, born a Lutheran, once assented to the spirit of Luther and Anthroposophy . . . but later changed his mind profoundly.

To me, this matters. Because Tomberg’s thinking has convinced me, just as my experience of the Church and her Sacraments has convinced me.

It matters for another reason, too: these Enlightenment monsters are now tearing us to shreds.

And the great irony in all I write is—again—just how very acutely Martin sees and reveals these Enlightenment monsters in his books.

I need the kind of acute, I would say Hermetic, analysis Martin makes of modernity. I need his profound Sophiological insight.

And I need the Church, too . . . like the air that I breathe.

And so my own response to Enlightenment monsters is Tomberg’s response: Both/and.

If Michael Martin or others despair of the Church, I cannot help but feel pain. But, again, my pain goes beyond anything personal. It is certainly not to judge Martin—not having walked an inch in his searing moccasins—and remaining filled as I do with respect for his forty year quest to follow the Star.

As I have said, I respect Martin’s outrage at the atrocious abuse in the Church, so much that I have asked myself: ‘Roger, is your own heart less Christian’s than Martin’s? Are you too comfortably numb?’

Whatever the true answer to these questions, I trust in a different road, the road Tomberg led me to. Numbed or not, my faith abides in the Utter Miracle of the Church and her Sacraments.

No matter how much hypocrisy and cruelty there may be in today’s Vatican, no matter how many Theodore McCarricks there are in the Church, monsters lurk everywhere in our vicious, fallen world. And the Church has always had her share of them. That Judas was an apostle both illustrates and symbolises that the Church was ever profoundly fallen in her human side and ever will be . . . till the Fall be undone.

Yet I fear a great number of noble souls—Berdyaev, Steiner and many more—may not account for this when they fault the Church. Where such men blame the Church, I want to say: ‘Look deeper, look deeper’ . . .

Tomberg, I trust, did look deeper. His writings are pervaded by a tragic awareness of the Fall and this, I imagine, is partly why, in his maturity, he never followed Berdyaev and Steiner’s criticism of the Church, despite obvious debts to both men. For he also saw how we desperately we need the Church.

At any rate, I have been penetrated deeply by Tomberg’s call to love, honour and obey the concrete Church on earth (and not a nebulous idea of the Church that all-too-easily suits our all-too-human whims).

A Different Life Experience: Through Christendom With Tomberg

But if I now see things very differently to Martin, perhaps it owes not only to Tomberg, but also to the fact I have very different experiences to him . . . leading to very different conclusions.

Some of these different experiences will be invoked now—along with further reflexions on how Tomberg could combine Sophiology, Hermeticism, dogma and even the kind of Catholic politics rejected by Vatican II. And here, of course, we have to do with the very heart of this piece: the quest for answers to the crisis of the West, whether this quest be Martin’s, Steiner’s, Tomberg’s or my own . . .

We begin, by way of departure, with a statement from Transfiguration, the likes of which are sprinkled through Martin’s oeuvre:

Christendom died a long time ago. The Oxford Movement, the Gothic Revival, and Traditionalism all failed to restore the golden age when Christ was King (a title used only ironically in the Gospels but embraced with fervor during the too-long centuries of Christianity’s flirtation with political power).

Michael Martin, Transfiguration, p. 35.

What can I say? Once I would have affirmed this—vigorously. For I was a progressive, enamoured of Anthroposophy and I followed the generally progressive Steiner’s lead that it is the future that matters: new wineskins are needed—not tired, old forms from the past.

But I had to grapple with the late Tomberg’s invocations of Christendom that shockingly start to appear in his Catholic works from 1944 on—in dizzying disjunction with all he earlier evinced as Steiner’s apostle.

Indeed, it is not too much to say I suffered a sort of vertigo, because Tomberg clearly did call for political power to support the Church! Anthroposophical anathema!

Thus Tomberg helped initiate a process whereby I could no longer vigorously affirm critiques of Christendom, the Gothic revival and suchlike.

Yet there is another factor here. And this is what I mean by a very different experience from Martin’s. For I am an American by birth who has lived in the ruins of Christendom for over four decades now . . .

I mean, of course, Europe. And maybe above all, Ireland where the embers of Christendom can be felt like nowhere else I know in Europe . . .

This is my life experience, providentially granted to me by God for a reason. Thus it is necessary to dwell on it contemplatively.

Dwelling contemplatively … this, too, forms part of Martin’s Sophiological message. Movingly, he writes about dwelling with experience, nature, phenomena—as well as people, including certain poets, philosophers and authors he loves: attending closely to the intimate beating of their hearts.

This, too, for Martin is Sophiology: not a critical reductive scrutiny of events or literature, according to prevailing postmodern norms, but listening with ears of love. In the process he listens, not only to their words, but their souls, their biographies and the cultures they were embedded in. This makes for rich engagement indeed.

For my part, I aspire, at least, to the same. I dwell with Belloc, Chesterton, Pugin, Waugh, Tomberg, de Gaulle . . . and I dwell with Martin. Here, I cannot help but ponder Martin’s biography so different to my own: one that encompasses being a biodynamic farmer, deeply rooted in Michigan, a professor of English; a father of nine children; a performing musician; a poet, a man of greater erudition than I possess. His quest, following the Star, leads naturally to very different gifts to my own.

But my own star led from America to living in eight different European countries. In particular, I know England. Not only have I stomped through that land for nearly two decades of my life, breathing in her culture and history, but my blood is English (save for that of a great grandparent from Galway).

Along the way, I have revelled in glorious Gothic revival architecture pioneered by Pugin, I have studied the effects of the Oxford Movement, which led to the English Catholic revival (Belloc went to Newman’s school and was mentored by Manning!), I have seen the work Joseph Shaw’s Traditionalism achieves in England, bringing beauty, not to mention sanity . . .

Have Pugin, Newman, Belloc and Shaw restored Christendom to England’s green and pleasant land? No.

Is England an immeasurably richer place for their Catholic impulses?

Oh yes! I think to the England of Jane Austen’s time, just prior to the Catholic revival.

Enlightenment aridity was in the ascendant, Catholics were discriminated against as a superstitious, priest-ridden lot and people gasped that a brilliant, cultivated man like Newman could stoop to join the riff-raff of the nation . . .

Knowing England gives me a very different perspective to many North Americans, including Martin. I shudder a little thinking of ‘Jane Austen’s England’ extended through time—without these Nineteenth Century glories Martin dismisses.

But for this, I think, one has to know England; Americans lacking this first-hand knowledge might pick up a little from history or indeed Jane Austen (or even a Jane Austen film adaptation) but I doubt they could ever feel what I feel, whether shuddering or not . . .

At any rate, Rudolf Steiner knew England and did not feel as I do. I imagine he might well see that gorgeous Pugin architecture as an atavistic throwback to medieval times. Instead, he would point to the need for his own organic architecture.

Like Martin, Steiner calls to the future. And Steiner would not celebrate the Catholic Ireland I celebrate, transformed arguably even more than England by the Gothic revival. All over Ireland I have partaken of His Body and Blood in these Neo-gothic churches strewn across this even greener land . . .

Knowing England and Ireland as I do, following the Star, hurts and haunts me in ways many Americans are neither hurt, nor haunted.

A Call to Christendom Renewed

All this, I think, prepared the way for me to understand Tomberg’s post-1944 invocation of Christendom, even call to Christendom. For the call to some sort of Christendom renewed—with a world politically ordered to both Divine and Natural Law—is what emerges from 1944 onwards in his legal and political writings. Only such a world can save us from catastrophe: here is the message of these books, beginning with The Art of the Good in 1944.

Now what Tomberg meant by this is hardly a restitution of the pre-1789 ancien regime pure and simple, even if it contains astonishing affirmations of Christian monarchy, the Emperor of Christendom and more.

At any rate, all this stands in shocking contradistinction to Rudolf Steiner’s Anthroposophy. Steiner, as we have noted here and elsewhere, generally supported the secularising revolutions against Christendom. But after 1944, Tomberg only spoke of these with profound regret.

Indeed, he said we must expect utter disaster if we cannot re-organise society according to the higher forms of law destroyed by modern secularism. Living without Divine Law is not sustainable in the longer term.

Now, many in the modern West will simply dismiss Tomberg’s call to a world ordered by Divine Law and Natural Law, which demands a world of ecclesiastical and political hierarchy (themes most evident in his great jurisprudence works of the 1940s and 50s but still present in the Tarot and Lazarus book as well.)

But Tomberg was not a man of the modern West! No, as I have endeavoured to point out in this series of posts and videos on Tomberg, he was a Russian, brought up with the Russian Orthodox liturgy in the time of the Tzar Nicholas II.

He was, then, a man of the East, who can hardly be identified with the progressive Western revolutionary idea that most English and Americans drink in with their mother’s milk . . .

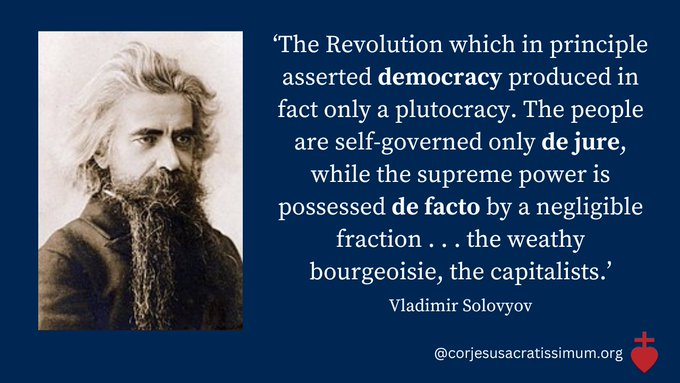

In his jurisprudence works Tomberg wrote critically not only of the Reformation, unknown in Russia, that lies at the fount of Western revolution, but also Locke and Rousseau, leading spirits of 1776 and 1789, and he certainly would have concurred with his Russian predecessor and Sophiologist Solovyov writing:

The essential character of Western civilisation became defined as extra-religious with the French Revolution, which attempted to build an edifice of universal culture and to organise humanity upon purely secular external principles. Human rights rather than the former divine right were proclaimed to be the basis of the social order [but] the social order must rest upon some positive basis. Either that basis has an absolute, supernatural and superhuman, character or it belongs to the conditional sphere of the given human nature. Society rests either upon the will of God or upon the will of the people, the popular will.

Vladimir Solovyov, Lectures on Divine Humanity, p. 3-4.

Yes in shocking contradiction to Steiner who was positive about the essence, at least, of 1789, Tomberg joined with Solovyov’s Eastern doubts of Western secularism. And it is difficult not to imagine him further concurring with Solovyov that:

The Revolution which in principle asserted democracy produced in fact only a plutocracy. The people are self-governed only de jure, while the supreme power is possessed de facto by a negligible faction . . . the wealthy bourgeoisie, the capitalists.

Vladimir Solovyov, Lectures on Divine Humanity, p. 3-4.

At any rate, Tomberg not only shared Soloviev’s rejection of the revolution, he wrote a series of books of legal and political philosophy which also drew on Soloviev’s own political thought. And again these books point to some sort of Christendom renewed as the only hope for our troubled society. Moreover such thoughts continue to resound in his final writings Meditations on the Tarot and Lazarus Come Forth—for example in the meditation on the Emperor—even if they are not as prominent there.

Saying this, I am certainly aware that Tomberg’s letter on the Emperor is all about authority, rather than power as such.

Still, things like the rejection of the great secularising revolutions as well as the call for the State to support the Church and both ecclesiastical and political hierarchy feature throughout Tomberg’s Catholic works and thinking.

More Western readers, I think, would suffer the same vertigo I once did, if they only paid attention to the evocation of hierarchical Christendom that factors in everything Tomberg ever wrote after 1944.

Now a year ago, I released a nearly five-hour video (!) concerning these things, concerning Christendom, as well as my own personal twenty-five year journey with Tomberg and his work. It came to me to do this video in deep, silent prayer on January 3rd 2022. I then took six months to make it.

This video—called Through Christendom With Tomberg—is invoked for different reasons. First, it reveals my own journey, following the Star. Moreover, those seeing the entirety should note certain things. They will see my deep respect for Martin’s work, and his dwelling with Tomberg over decades. And they may also see how Tomberg can lead each of us in very different directions.

For in the course of that video I point out that Meditations on the Tarot is like a hundred books rolled into one – a kaleidoscope, dazzling yet profound, of theology, philosophy, psychology, history, Christian mysticism as well as the Christian Hermeticism of not only the French but also the Germans. (For again when Tomberg speaks of Hermeticism, he includes figures like Boehme, Goethe and Steiner, too.)

The Tarot book also features a historical critique of modernity, beginning with the Reformation of which Tomberg was so unusually severe. It highlights, too, the grave concern that our world becomes ever more mechanical and materialistic. And it further entails the great Catholic saints Tomberg repeatedly evokes, including St. Francis, St Thomas Aquinas, St Bernard of Clairvaux, St John of the Cross, St Terese of Avila, St. Ignatius of Loyola, not to mention the Holy Priest of Ars. And it entails of course the thinking of the Russian Sophiologists.

This it does because, as I have said many times now, particularly in my videos, Valentin Tomberg was gravely concerned with the Fate of the West. And his ‘hundred books rolled into one’ constitute a project to address the Fate of West. A project that needs to be guarded, I believe, and neither conflated, nor confused with the earlier Anthroposophical project he regretted.

For the more the twenty first century ‘progresses’, the more we see it is a dangerous place. Who knows what further horrors lie in store after the spectral possibility, at least, of human-manufactured viruses and ensuing pandemic, climate change, growing mental illness and cultural schizophrenia, round the clock drugs like the Entertainment industry and other features of the technocracy that Martin uncovers.

There is need, great and terrible. That need calls out for the kind of sophic quest for the Star—original, bold, refusing to kowtow to Herod and his people—that Martin has carried out for decades now.

And in my view, it also calls for the Church, her Sacraments and continuity with Catholic Tradition that is neither surgical, nor revolutionary.

Both/and.

An Essay Born from Following the Star . . .

And that, I suppose, is really what lies at the heart of this lengthy, complex, perhaps at times mysterious, essay. It is a piece that started with a simple desire to review Martin’s latest book Sophia in Exile, while testifying to the power and beauty I found in his earlier books, most particularly Transfiguration.

But events, interior and exterior, intervened and this became something more. Partly it became a piece with Traditionalists in mind, who may not always understand my advocacy of much, though not all, Martin is saying.

Because I believe some are concerned by my advocacy for Martin’s work, a work that increasingly seems to disparage what they and I, too, find most precious in all the world.

For they, like me, place their greatest hope in the miracle of the Catholic Church, as it spreads out across the planet celebrating the Sacraments, perhaps two or even three hundred thousand times a day . . .

I trust, with them, that there is no hope for the world but that this Church, along with the Orthodox churches of the East, are regenerated.

And like them and like Tomberg, I am confident in this regeneration.

Yes, these things and more formed part of the mysterious processes, mentioned from the outset, that led to this perhaps enigmatic essay. If it is enigmatic, it is because it expresses something at the core of my life, my soul’s thirst for answers to the Crisis of the West, engulfed in materialism as never before.

Also at this core is the fact that I am a former New Ager, later follower of Steiner, who once believed the way forward for the world lay in things like Theosophy and later Anthroposophy and Anthroposophical cognition. I found it unbelievably tough to become Catholic, that is, really Catholic.

I managed it, though, via graces not everyone has: Tomberg’s wisdom and also the lived experience of Europe, including France and Ireland, above all, Ireland . . .

I have been moved, moved to my core by Irish Catholicism (and the real thing is so different to the stereotypes imported to the rest of the Anglosphere, whether these be of a chic ‘Celtic Christianity’ or darkened horror stories of brutal priests and nuns).

And so I walk a different road than Martin, Berdyaev or the Anthroposophists: a road of Catholic tradition and faith and Sacraments. But this does not mean I cannot honour Martin’s pained indignant heart, rightly outraged by McCarrick, Pope Francis, GMOs, viruses and vaccines and much other malign fruit of Enlightenment rationalism that Church bureaucrats remain all too often numb to.

Martin is not numb! God bless him for this! God bless him, too, for cultivating a garden (cf. Tomberg’s Sixteenth Letter in the Meditations) whilst following the Star. That garden not only includes his biodynamic vegetables, fruits and milk of goats, but the gardens of great poets and Sophiologists.

Here I end this strange, meandering piece, honouring the work of a Hermeticist following the Star, yielding so many gifts along the way. Here I end this piece, after strange intimate processes dictated I do more than simply review Sophia in Exile. Here I end this piece, knowing the world desperately needs the Sophiology the Star led Martin to, yet trusting, too, where the Star leads me.

If you care about answers to the technocratic nightmare of our times, you may learn things from Martin that you will find in few (if any) other Christian thinkers today. Yes, you may need to tolerate certain pained words about the institution of the Church, words that certainly strike me as unfortunate (eg. ‘Sacramental machine’) but you need not join the man in his despair.

Read Sophia in Exile and Transfiguration, especially if, like me, you seek solutions to the mayhem bred by tenebrous powers, both technocratic and preternatural, while you walk a road with Tomberg seeking answers for the West . . .

Read Martin, I urge, but do not forget the Body and Blood of Our Lord appearing every day on hundreds of thousands of Catholic and Orthodox altars across the planet.

Both/and.

Buying Books at Amazon Through These Links Gives Us a Commission. This Supports Our Apostolate. Thank You if You Can Help Us Like This!