By John R. G. Hassard

Introduction:

Here is the fourth instalment of the 1878 Life of Pius IX by John R. G. Hassard – another old Nineteenth Century Catholic book in our Tridentine Catholicism Archive. (For more about this, see our introduction to the first instalment here.)

Hassard’s book appears here in nine chapters:

- Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 1: Early Years in Christendom Despoiled

- Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 2: The Carbonari and Other Secret Societies

- Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 3: The Conclave Elects a New Pope

- Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 4: Conspiracy, War and Revolution

- Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 5: Annexation of the Papal States

- Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 6: Counter-Revolution and the Syllabus of Errors

- Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 7: Ultramontanism and the First Vatican Council

- Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 8: The Seizure of Rome and the Last Stand of the Papal Zouaves

- Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 9: A Prisoner of the Vatican

In this chapter, we continue to encounter an outstanding subtext to Hassard’s work – that of the secret societies fomenting revolution in Nineteenth Century Europe.

What is involved here is a very complex picture of European history that has been long-forgotten by many people in the Twenty-First Century. In previous instalments, we have tried to give the modern reader, ignorant of such, some of the most rudimentary elements that may make Hassard’s book clearer.

Whilst the reader is referred to those earlier instalments for more details, let us quote some of the most salient points again here:

Revolutionary movements against Altar and Throne continued to spring up in countries like Spain and France (which experienced a second revolution in 1830).

All this Hassard – along with countless others! – believes is deeply indebted to the work of masonic-type secret societies such as the Illuminati and the Carbonari.

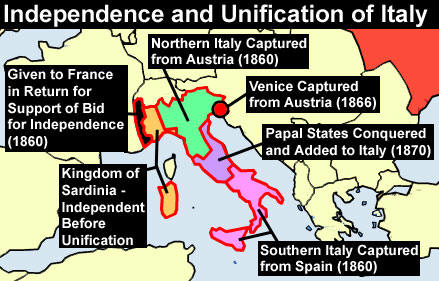

The picture becomes even more complicated when we remember that before 1870, there was no united Italian nation. Instead, the Italian peninsula was divided amongst several reigning powers.

There were, of course, the Papal States which had been ruled by the Popes for centuries. There were also smaller independent Italian states such as the duchies of Tuscany and Parma. Finally, parts of what is now Italy today were commanded by Spain and Austria.

During the Nineteenth Century, a movement of Italian unification arose, commonly known as the Risorgimento. That movement is closely linked with such revolutionary figures as Mazzini, Garibaldi and Cavour.

All of whom – amongst many other largely-forgotten names – we meet in the pages of Hassard’s book and now in the webpages of this site.

The interested reader may be referred to either the old 1917 Catholic Encyclopaedia (available online here) or Wikipedia and other sources on the web to explain who these men were and what they did.

We cannot enter into that level of detail here. Suffice it to say that during the reign of Bl. Pius IX (1846-1878), the Risorgimento succeeded.

Through interlinked processes of insurrection, war and conquest, the once-separate Italian entities were fused to become form the state we know as Italy today.

A map of these processes – though somewhat simplified – may help the modern reader to understand:

Today, many a reader will likely consider all this in anything but positive terms – scarcely realising how much vast numbers of the Italian population were once staunchly opposed to the revolutionary Risorgimento.

For they feared, among other things, that Christian civilisation would be destroyed.

And given how many priests were killed, how many convents and monasteries were ransacked, how many churches were destroyed by the Risorgimento – they had every right to be frightened …

The Risorgimento was not purely and simply a quest for Italian unification. As Hassard observes:

It is certain that the sentiment of unity was not the origin of the revolutionary movement in the Italian States, and will not be its end. The movement was active before national unity was thought of and is still active after national unity has been attained.

Again Hassard, like countless others of his time, believes that the Risorgimento was only possible through conspiracy and the skulduggery of masonic-type groups such as the Carbonari and the Illuminati – among others.

How true is this understanding?

To truly answer this question is beyond almost any man, except perhaps the most diligent, competent and unbiased of historians and researchers.

Alas! An unbiased historian is the rarest of creatures!

I can only offer my own opinion, dear Reader – with my own biases.

I think the conspiracy claims of Hassard are worth listening to. That is why we publish them here.

However, ‘worth listening to’ is not the same as as a full endorsement of everything Hassard says in these (web) pages. Again, I myself am far, far from competent to judge these matters.

I only know that today’s liberal sceptical historians – usually hostile to Catholicism – are also far from competent to judge these matters.

People are all-too-easily written off these days as cranks or conspiracy nuts.

So be it – then the great Popes of the Nineteenth Century must also be cranks and conspiracy nuts. For great men such as Bl. Pius XI or Leo XIII frequently warned of the dangers of such masonic groupings to the world.

What Hassard writes below is mainly concerned with the Carbonari in Italy …

We cannot say much more in this short space. More will be said in the succeeding introductions to this series …

But the interested reader must follow up these matter for himself.

Again, either the old Catholic Enyclopedia of 1910 (online here) or Wikipedia can explain much that is forgotten in these webpages – although Wikipedia, I think, certainly suffers the biases of contemporary liberal historiography. Caveat Lector!

Let us now add some further scant, all-too-scant notes, that may help the reader to understand this fourth instalment better – which not only deals further with conspiracy and the secret societies, but also such matters as the First War of Italian Independence against Austria – which once controlled the northern parts of what is now Italy (see map above).

Also covered are the 1848 revolutions across Europe – including Rome – and the Pope’s flight from Rome after the revolution there.

Again the interested reader may wish to consult other online sources for French and Austrian history. For these two great Catholic powers are key to what happens here.

However, the reader will gather the essential from what follows: that, generally speaking, France was a far more liberal country at that time, whilst Austria was much more conservative.

She was commonly derided as reactionary and retrograde. But Austria was arguably far more alert to the anti-Christian threat posed by the revolutionaries.

The nature of this anti-Christian threat should become clearer if the reader continues with this series.

Suffice it to say, for now, that as the revolutionary Risorgimento proceeds, we will witness draconian measures such as the mass closure of religious monasteries, the appropriation of ecclesiastical property, the proliferation of anti-Catholic propaganda and education in newly secularised institutions.

Indeed, all of this is suggested by the nature of the 1848 revolution in Rome described below:

The Convent of S. Calisto, in the Trastevere, became a slaughter house … The pillage of private houses and the wanton destruction of public monuments were among the lesser outrages of this reign of anarchy.

And the official proceedings of the Government matched the lawless violence of the populace.

Ecclesiastical property was seized, convents were suppressed. The confessionals were taken to make barricades. … The shrines and altars were stripped bare. The palaces of the cardinals were sacked.

Profane rites were celebrated in St. Peter’s at Easter under the auspices of the Government, and a suspended priest gave a travesty of the papal benediction from the balcony.

The canons of St. Peter’s were fined for refusing to participate in such sacrilegious proceedings, and the provost of the cathedral of Sinigaglia was put to death for declining to hail the republic by a Te Deum.

It is, moreover, amply confirmed by what happened in Rome in 1870 many years later, after the Papal States finally fell to the invading armies of the Risorgimento.

As Hassard writes in the eighth chapter of this web series:

Almost the first act of the new rulers of Rome was to confiscate the property of all ecclesiastical bodies and foundations whatsoever, save a very few which were exempted by name.

This left nearly the whole body of the clergy destitute, and cut off the sole support of the churches and the parish priests.

Next came the suppression of all religious orders; 50,000 persons were thus turned into the street without the means of subsistence.

The clergy were pressed into the army.

Convents, churches, charitable and religious institutions were seized and sold, or converted to the uses of the Government. Schools were broken up; education was secularized.

The revenues of most of the bishops throughout the whole kingdom were cut off, and the support of the Italian episcopate was thrown upon the Sovereign Pontiff.

The spirit of the Italian laws and the Italian administration was thoroughly and in everything anti-Catholic and anti- Christian.

All religious processions were prohibited.

The chapels and crosses which pious hands had erected in the Colosseum to commemorate the martyrs of the first centuries were torn down, and the name of Christ was chiselled off the facade of the Roman College.

Vice, violence, sacrilege, atheism everywhere followed in the track of the Piedmontese armies. They carried riot into the very churches.

From all of this, the reader may be able to understand how and why Hassard was a clear apologist for Pope Pius IX – as indeed were nearly all Catholics of the era who dreaded the anti-Christian nature of the revolution which began in France in 1789!

Again, we hardly claim at this late date to know whether Hassard is correct in everything he claims about the conspiracy against the Church.

We simply say his voice deserves to be heard – particularly now that history is drowned in apologetics for a liberal secularism – a liberal secularism that all-too-conveniently forgets the abuses and even atrocities with which that secularism was engendered.

But let us now turn to Hassard, who after considering the early years the future of the pope, Bl. Pius IX – now turns his attention to the political situation of 1848 – RB.

The Continued Threat from Masonic Type Societies

Thus cheered and honored at home and abroad, by friends and by enemies, the Papacy shone with a glory such as it had not displayed since Leo X. But under the outward show of peace the Pontiff well knew that conspiracy was active.

Many careful foreign observers reported, even when the songs of triumph were loudest in the streets of Rome, and when the multitudes came by torchlight to kneel in the piazza in front of the Quirinal and ask for the Pope’s blessing before they went to bed, that these transports were not entirely sincere.

After the proclamation of amnesty and the relaxation of police surveillance, thousands of the revolutionists poured into Rome and made that city the nursery of plots.

The instructions of Mazzini were carefully obeyed:

‘Profit by the least concession to assemble the masses, if only to testify gratitude. Festivals, songs, assemblies give the people a feeling of strength and make them exacting. A king grants a more liberal law; applaud it, and demand that which must logically follow. Associate, associate!Every thing is in that one word.’

So while on the one hand the gratitude of the people was never allowed to flag, on the other they were never allowed to feel that their demands had been satisfied. Every concession inflamed the popular uneasiness.

Every demonstration in honour of the Holy Father covered a revolt in disguise. ‘We must make him our political bauf gras’ said Mazzini.

At festivals, the agents of Young Italy and of the secret societies mingled with the crowd, and added seditious cries to the genuine acclamations of the people. When the Pope walked abroad they followed him, to interrupt the cheers for the Pontiff with demonstrations against his government.

Less than two months after his accession, as he drove under an arch erected in his honor, the mob stopped some of the prelates of his suite, and refused to let them pass beneath the triumphal emblems.

The shouts of ‘Viva Pio Nono!’ soon changed to ‘Viva Pio Nono solo!’ and with them were heard ‘Down with the Jesuits!’ and ‘Death to the retrograders!’

Rumbles of Sedition

Every gathering of the people, a scientific congress at Genoa, a patriotic anniversary, a working-men’s debating club, a picnic, a parade became an occasion of political agitation.

In the taverns where Angelo Brunetti, nicknamed Ciceruacchio, or ‘Little Cicero,’ fascinated the common people by his good-fellowship and his fluent tongue; in the cafes; in the Circolo Romano and the Circolo Popolare; in the parlours of Lord Palmerston’s special envoy, Lord Minto, where gathered a strange company of advanced Liberals Charles Bonaparte, Prince of Canino, the radical of rank; Ciceruacchio, the leader of the rabble; Sterbini, the poet, physician, and journalist; and Galletti, the pardoned exile, who had just sworn to shed his blood for the Pope, if the Pope would have it.

The complaint was nightly heard that Pius was too slow: that there were too many ‘reactionists’ around him; that there ought to be more laymen in the administration and more power for the Consulta of State.

And gradually out of all this agitation, a demand for the destruction of the existing Italian governments was shaping itself into expression.

In April, 1847 a festival was held ostensibly to celebrate the anniversary of the foundation of Rome, and there was a great meeting at the Baths of Titus, where Massimo d’Azeglio made an address, and referred amid thunders of applause to ‘the expulsion of the Goths, Huns, and other Vandals ‘ from Italy an allusion which, of course, there was no mistaking.

In the summer of 1847, great preparations were made for the first anniversary of the proclamation of amnesty. Suddenly, Rome was thrown into wild confusion by the rumour of a reactionist conspiracy.

It was gravely alleged that Cardinal Lambruschini, the Austrian Government, and the general of the Jesuits had concerted a plot to seize the Pope and carry him off.

The proposed celebration was forbidden. The people flew to arms. Lists of cardinals and others accused of complicity in the nefarious scheme were posted all over the city, with the inscription, ‘All devoted to the eternal execration of the people.’

The suspected cardinals fled. For two days and nights the police was helpless, and Rome was entirely in the hands of Ciceruacchio.

It was this democratic tribune who mounted the steps of the Pope’s carriage one day with a tricolour flag inscribed, ‘Holy Father, rely upon the people,’ while the people rent the air with execrations of the Jesuits, the ministry, and the police.

Mr. Legge describes an impressive scene at the Quirinal when a multitude, half loyal, half seditious, came to cheer the Pope for some popular act.

‘ The Pontiff showed himself at the balcony, and intimated his wish to address the crowd. The silence was profound, and he spoke as follows:

Before the benediction of God descends upon you, on the rest of my people, and, I say it again, on all Italy, I pray you to be of one mind and to keep the faith you have sworn to me, the Pontiff.

At these words the silence of deep feeling was broken by a sudden thunder of acclamation, Yes, I swear, and Pius IX proceeded :

I warn you, however, of the raising of certain cries that are not of the people but of a few individuals, and against making any such requests to me as are incompatible with the sanctity of the Church; for these I cannot, I may not, and I will not grant. This being understood, with my whole soul I bless you.

Farini quotes a secret letter from the French Prefect of Police to the Minister of the Interior, dated in January, 1848:

I am told that Mazzini is come to Paris, in order to take counsel with such of his friends as are here about the means of raising money to despatch emissaries into Tuscany and Piedmont and to Rome and Naples, who will have in structions to second the existing movement and to ingratiate themselves with the patriots. They have been recommended to study the character of Ciceruacchio, the popular leader in Rome, and to exert themselves to draw him into their faction by induc ing him to believe that everything will be done with a view to the greater glory of Pius IX.

In a word, the plan of Mazzini is as follows: to avail himself of the present excitement, turning it to account on behalf of Young Italy, which repudiates monarchy, under whatsoever form, and to effect this by raising the cry of * Viva! for the Duke of Tuscany, for Charles Albert, and for Pius IX.

The Secret Societies Provoke Austria

A letter of Mazzini’s, written in 1847, had taught Young Italy that their best policy was to inflame the popular hatred of Austria, then provoke Austria to attack them, and in the heat of war accomplish the rest.

The plan nearly succeeded. Alarmed at the aspect of affairs in Central Italy in the summer of 1847, Austria marched a body of troops into the papal territory.

The treaty of 1815 gave her the right to place a garrison in the citadel of Ferrara. She claimed a further privilege and took military possession of the whole town.

Against this usurpation, the Sovereign Pontiff protested in the most energetic terms, and after a diplomatic contest of several months duration the Austrians were forced to retire.

But the occasion which the secret societies desired had been given. A cry for war and independence resounded from the Gulf of Genoa to the Bay of Naples.

Loud clamours were raised in Rome for the reorganization and strengthening of the army. An imperative demand was made in the form of a somewhat threatening address to the Consulta of State for the immediate calling out of the Civic Guard in every part of the country. And it became evident that the Civic Guard could not be trusted to obey the Pope’s orders.

Devotion to Pius IX and Papal Order

While the conspiracy was thus hurrying to a crisis it was remarkable that the devotion of an immense majority of the people to the person of the Sovereign Pontiff remained unimpaired.

If seditious cries interrupted the shouts of applause, it must nevertheless be admitted that they did not mix well, and that the rebellious demonstrations were more or less forced and theatrical.

When the tendency of the popular meetings became apparent the Pope took pains to discourage festivities proposed in his honor, and at the slightest intimation of his wish they were cheerfully abandoned.

Even the cry for independence stimulated alike by the insolence of Austria and the enthusiasm of Gioberti though it was loud and wide-spread, was by no means general.

Count Rossi was an Italian, an earnest Liberal, and a shrewd observer, and he was using his great influence to hasten the Pope’s reforms and to extend their scope; but, although his sympathies were all with the party of unity, he looked upon an Italian ‘people’ in 1847 as little more than a phantom of the imagination.

‘It is a war of independence which you would invoke,’ said he.

‘Be it so; let us calculate your forces. You have 60,000 regular troops in Piedmont, and not a man more. You speak of the enthusiasm of the Italian populations; I know them. Traverse them from end to end; see if a heart beats, if a man moves, if an arm is raised to commence the fight. The Piedmontese once beaten, the Austrians may go from Reggio to Calabria without meeting a single Italian.’

The Liberal Measures and Reforms of Pius IX

I know of nothing finer in the history of revolutions than the attitude of Pius IX in these days of excitement and danger. Generous, affectionate, and patriotic, neither threats, nor remonstrances, nor ingratitude, nor personal peril could turn him from the course which he believed to be best for his subjects and best for Italy.

The French Government informed him privately that it had placed 5,000 troops at his disposal to secure the tranquillity of the Pontifical States, and they were ready to embark whenever he should give the word.

But he would not have them. He had trusted himself to his people, and he would trust them to the end. He granted the demand for a reorganization of the army. He appointed the Piedmontese General Durando to the chief command. By a special proclamation he committed the defence of his person and of the Sacred College, the protection of life and property, and the preservation of order to the Civic Guard.

By a new motu proprio he made the Council of Ministers more popular. The cabinet underwent many changes. Gizzi was succeeded by the Pope’s relative, Cardinal Ferretti; Ferretti gave place to Cardinal Bofondi; Bofondi was followed by Cardinal Antonelli; and every change was regarded as an advance towards constitutionalism.

Laymen were appointed to the highest offices in the administration, all the ministerial posts being thrown open to them except the Secretaryship of State, which is quite as much concerned with eccle siastical as with secular affairs.

The Antonelli cabinet included Galletti, Minghetti, Farini, and Prince Aldobrandini, all laymen and all leaders in the popular party. A layman of the popular party was also placed at the head of the police.

But when the rights of the Church, the principles of jusiice, the sanctity of laws were attacked, the Pope was as firm as adamant and as fearless as a lion.

When the Consulta of State came together with great pomp and rejoicing in the midst of a general excitement, he said frankly in his address at the opening of the session:

He would be gravely mistaken who should see in this Council I have created the realization of his own Utopias, or the germ of an institution incompatible with the pontifical sovereignty.

Still earlier, in what may be called the noontide of his popularity, he announced by proclamation that he should pursue the course of political reform only:

so far as was consistent with the temporal sovereignty and that independence in the exercise of the primacy for which God willed that the Holy See should have a temporal principality.

And when he published the fundamental statute in 1848 he said plainly that this was the limit of his concessions: ‘ I have done all I can. I shall do no more.’

Those who professed to be shocked by the claims of the encyclical and Syllabus of 1864 strangely forgot that Pius IX preached the same politics as long ago as 1846, and never preached any other.

1848: Revolution Across Europe

WE know only imperfectly the hidden springs of action of that year of revolutions, 1848; but suddenly, as if by concert, the insurrection flashed up almost simultaneously all over the Continent.

Naples was in revolt. Venice rose under the inspiration of the patriot Manin. The Milanese flew to arms. Louis Philippe [of France] fled for his life. The Republic was proclaimed at Paris.

There were barricades at Berlin. There was fighting at Vienna. The Italian cities were intensely agitated, and Rome was the most feverish of all.

The municipality waited on the Pope and demanded a constitution after the example of Naples and Tuscany. But already the Holy Father had determined to grant one, and a commission had been for some time engaged in its preparation.

The constitution, or statute f on dame H tale, was promulgated on the i4th of March, 1848.

It provided for a Senate, composed of the College of Cardinals, and a legislative body consisting of a High Council nominated by the Pope, and a House of Deputies elected by the people.

The ratio of representation was to be one to 30,000. The elective franchise was based on taxation. The imposition of taxes and the voting of the budget, with the exception of an annual allowance of 600,000 crowns for the maintenance of the Pontiff and the papal court, the diplomatic service, etc., was left to the Deputies.

Even in publishing this constitution, however, Pius IX declared that the pontifical authority over matters essentially belonging to the Catholic religion and its rule of morals would not be surrendered; and, moreover, the Deputies were forbidden to interfere with ecclesiastical or mixed affairs. All laws required the sanction of the Pope, which was to be given or withheld in secret consistory.

The ‘party of action’ soon began to deride this constitution as a delusion, but most of the people received it at first with delight; and in the exuberance of their joy the Mazzinians made a fresh attack upon the Jesuits and mobbed the Gesu.

It was perhaps the highest possible honor to the illustrious Society of Jesus that the extreme radicals always pursued them with relentless animosity. The Pope tried in vain to protect them.

It became evident that their continued presence in Rome would be a constant cause of disorder; and, unwilling to be the occasion of bloodshed, they closed their establishment, some of the fathers taking flight, others finding shelter in private houses.

First War of Italian Independence

Meanwhile, Young Italy found a leader in the King of Sardinia, and the war of independence broke out amid the acclamations of the peninsula.

No sooner had the insurrection declared itself at Milan and Venice than Charles Albert, with a well- appointed army, crossed the Piedmontese frontier to co-operate with the patriots in the expulsion of the Austrians.

Volunteers from all the Italian States hurried into Lombardy. The people threw themselves into the movement without waiting for their governments.

The Pope was urged to declare war against the German intruder. He refused. The common father of the faithful must be at peace with all the world. But to defend his frontier he sent Gen. Durando, with 17,000 men, to guard the line of the Pope, strictly commanding him not to cross the boundary.

The course of the Pope at tin s juncture has been the subject of unreasonable criticism. He has been accused by one party of weakness in yielding too much, by another of vacil lation in retracting his first concessions.

Both are wrong. His policy was clear and consistent from the first.

The Pope as Friend to Italian Independence

There is no doubt that he was always an ardent friend of Italian independence; but he wished to obtain it peaceably, remembering, above all, that the bark of Peter is not a man-of-war. His sympathies could not tempt him from his duty.

In the latter part of his life, recalling some of the events of this period, he related a conversation with one of the radical ministers who waited on him at the Quirinal to urge a declaration of war:

He was a republican, who played the part of a tribune of the people, but he came into my cabinet timid and cringing, and said in a low voice that disturbances had been occasioned by one of my allocutions, in which I notified to all the powers my refusal to join in the war against Austria. To which I replied, * The Vicar of Christ ought to be at peace with all.

‘But, Holy Father’ replied this man, ‘you ex pose yourself to great misfortunes.’

‘I will bear them. Whatever they may be, I will do nothing contrary to honor, contrary to justice, contrary to conscience, contrary to religion.’

While he totally rejected the Mazzinian conception of a unitary Italian republic, he was, nevertheless, a warm partisan of Italian unity, as well as of Italian independence.

We have seen that, in conversation with Count Rossi in 1846, he pronounced the plan of a confederation then talked about as chimerical. But he himself was the foremost supporter of another scheme of union, based upon a league of constitutional states, and somewhat resembling in certain features the ideal of Gioberti.

He proposed that a diet of deputies from the Italian powers should assemble at Rome, primarily to arrange a customs union, but with the further view of a closer and a more general association of interests.

Several of the States gave their assent, and Pius despatched Monsignor Corboli Bussi to procure the adhesion of Charles Albert.

But the project was defeated by the ambition of Piedmont, which aimed at a union under the crown of Savoy and the intrigues of the Mazzinians and Carbonari, who only desired a democracy.

Defence Against Austria

The movement of a defensive army to the frontier was merely an ordinary and proper measure of precaution, but it suited the purpose of the secret societies to acclaim it as an act of war.

A great public meeting was held in the Colosseum to ratify the new ‘crusade,’ and there the Barnabite monk Gavazzi, masquerading in the character of a new Peter the Hermit, and brandishing a tricoloured cross, roused the fanaticism of the multitude with his fiery speech, and conjured them to swear by the symbol of their faith to march against the ‘barbarians,’ and return no more until the last of the hated race had been chased out of Italy.

A clamorous mob rushed to the Quirinal, and insisted that the Pope should bless their banners. Five of the people were admitted. ‘My sons,’ said the Pontiff, ‘do you know where you are going?

‘ Where our chiefs lead us, Holy Father.’

‘ That is very well; but perhaps it is better that you should learn your destination from me. Know, then, that you are only to defend the frontiers of our States. Take care not to cross them; for in doing so you will not only violate my orders but lay upon the pontifical troops the responsibility of an act of aggression which they must in no case assume.

Go, then, but no further than the frontier.’ And blessing the papal standard which one of them held in his hands, he thus dismissed them.

The language of this address was highly distasteful to the popular leaders. It was not repeated to the crowd. Only a report was spread abroad that the Holy Father had blessed the expedition; and so the army began its march.

There were 7,000 regular troops and 10,000 motley volunteers, the flower of the nobility and the dregs of the wine shop; the most gallant youth of Rome and the scum of all the political clubs of the Continent.

They hurried through the Romagna, gutting taverns and hunting Jesuits by the way; one day exchanging cheers and embraces with the people of the towns through which they passed, the next day committing excesses which covered their cause with dishonor and turned the public sentiment against them.

Our volunteer bands, says Emilio Dandolo, were composed of wrangling disputants, of lawyers, of popular tribunes with innumerable shades of political opinions, with inconsiderate hopes, instability of ideas, and proneness to suspicion.’

At their head marched Gavazzi, with the title of chaplain-general. On reaching Bologna Gen. Durando published, April 5, an extraordinary order of the day, declaring that the Austrians made war upon the Lord, and that the soldiers of the Pope, going into battle under the emblem of the cross, would conquer with the sacred cry, ‘God wills it!’

Then he formally placed his army at the disposal of the Sardinian king. It was afterwards discovered that this flagrant disobedience of the Pope’s commands was in accordance with secret instructions from Aldobrandini, the papal Minister of War!

It was impossible for the Holy Father to remain silent under such an outrage. He repudiated Durando’s order of the day in the official press, and he spoke more fully in the allocution of April 29:

Seeing that some desire that we, too, along with the other princes of Italy and their subjects, should engage in war against the Austrians, we have thought it convenient to proclaim clearly and openly in this our solemn assembly that such a measure is altogether alien from our counsels, inasmuch as we, albeit unworthy, are the vice gerent upon earth of Him who is the author of peace and the lover of charity; and, conformably to the function of our supreme apostolate, we embrace all kindreds, peoples, and nations with equal solicitude of paternal love.

But if, notwithstanding, there are not wanting among our subjects those who allow themselves to be carried away by the example of the rest of the Italians, in what manner can we possibly curb their ardour?

‘And in this place we cannot refrain from repudiating, before the face of all nations, the treacherous advice, published in journals and in various works, of those who would have the Roman Pontiff to be the head and president of some sort of novel republic of the whole Italian people. … In grievous error are those in volved who imagine that our mind can be seduced by the alluring grandeur of a more extended temporal sway to plunge the country into the midst of war and its tumults.’

This declaration came none too soon. For some time the radical faction in the ministry had been in the habit ot counterfeiting the sovereign’s assent to measures of which he disapproved. If the army was to make war against his will his reign was at an end.

The allocution was Rome by a general explosion of wrath. The cry of ‘ Treason!’ rang through the streets.

Sterbini and Ciceruacchio harangued the clubs. The more violent proposed to kill the priests. The mob attacked the post-office with the purpose of seizing the letters and searching them for evidence of treachery.

The Civic Guards flew to arms, frater nized with the people, defied the Pope’s orders, and posted soldiers at the doors of the cardinals. A proclamation of the Holy Father’s, counselling peace, was torn down with every mark of insult. The ministry resigned, and, after some days delay, was replaced by a more radical cabinet, at the head of which was Count Mamiani, one of the exiles of 1831, who had returned to Rome after the amnesty proclaimed by Pius, but had always re fused to sign the promise of loyalty demanded of those who accepted this act of grace.

Galletti remained in the new administration as Minister of Police. As a matter of course, Mamiani insisted upon a declaration of war against Austria; but upon this point he found the Pontiff immovable. On the 3d of May Pius addressed the following autograph letter to the Emperor of Austria:

‘ YOUR MAJESTY :

It has always been customary that words of peace should go forth from this Holy See amidst the wars that have bathed Christendom in blood; and hence, in the allocution of April 29, while we declared that our pater nal heart shrank from declaring war, we expressed in the strongest manner our ardent desire to contribute towards peace. Let it not, then, be distasteful to your majesty that we now appeal to your filial and reli gious sentiments, and with the affection of a father ex hort you to withdraw from a contest which can never subdue to your empire the hearts of the Lombards and Venetians, but must entail the dread series of calamities that attend on war, and from which your majesty s soul must recoil.

‘ Nor must the generous German nation take it ill if we urge them to lay aside resentment, and exchange for f.iendly relations of neighborly intercourse a domination which could never be useful or honorable while sus tained only by the sword.

‘ Let not your nation, therefore, justly proud of its own nationality, imagine that honor impels it to a bloody con test with the Italian nation; but rather let it generously acknowledge Italy as a sister, even as both arc daughters to us and dear to our heart; so that each may confine herself to her natural limits, upon honorable terms and with God s blessing.

‘ In the meantime we pray the Giver of all Light and the Author of all Good to inspire your majesty with holy counsel, and from our inmost heart we extend to y< u, to her majesty the empress, and to the imperial family the aposiolic benediction.’

To press upon the emperor the representations of tliis beautiful and touching letter, so full of the spirit of justice, patriotism, and enlightenment, Pius sent Monsignor (now Cardinal) Morichini to Vienna.

The mission was so far successful that Austria requested the British Government et to mediate between herself and Italy on the basis of the independence of Lombardy and the duchies, upon condition of an annual payment of 10,000,000 florins as their proportion of the national debt of Austria, an annual tribute of 4,000,000 florins, and the concession to Venetia of a separate administration with an army of her own under the sway of an Austrian archduke.’ * Legge

But this proposal was concealed from the Piedmontese king until after it had been rejected; and Lord Palmerston, who was all this while playing into the hands of the Mazzinian party, declined to accept the commission on any other condition than the absolute independence of certain Venetian provinces.

Meanwhile the agitation increased at Rome, fomented by fresh outbreaks at Paris, Vienna, and Naples, and by bad news from the army, where the Roman volunteers, routed in battle, revenged themselves by accusing their generals of ‘ treason,’ and literally tearing to pieces some obnoxious police officials who fell into their hands.

When the Roman Parliament opened, in June, Count Mamiani prepared a warlike ‘programme’ of the pontifical policy, in which, assuming to speak in the name of His Holiness, he declared that the Pope ‘dispenses the Word of God, prays, blesses, and pardons.’

‘Ay,’ added Pius, in replying some time afterwards to an official address, ‘but it is also his office to bind and loose. Priest as well as prince, he needs all the liberty that will prevent his action from being paralyzed.’ The opposition between the nominal sovereign and his ministers was an open scandal, and as Austria gained headway it became more and more violent. Galletti in the cabinet, Sterbini and the Prince of Canino in the Parliament, were the most furious of the demagogues.

In July, the Austrians invaded the Papal States again, and for a second time took possession of Ferrara. Pius protested with indignation, invoked the protection of the European powers, and prepared to expel the intruders by force. But the clubs welcomed this fresh cause of popular exasperation. The mob demanded arms.

The city gates and the Castle of S. Angelo were attacked. Sterbini and Gal letti made fiery harangues, declaring that ‘ the peo ple could not commit excess.’ A little later a courier, breathless and dusty, rode through the Corso announcing a great victory of Charles Albert over the Austrians.

The houses were illuminated; there was talk of forcing the clergy to chant Te Deum in the churches. But the next day it was discovered that the messenger who entered Rome as if from Lombardy by the Porta del Popolo had left the city only an hour before by the Porta Angelica, carefully gathering the stains of travel in an easy ride along the walls, and had been paid three dollars for the performance. Charles Albert had been signally -defeated; the war was nearing the end.

In Rome now the ministry was out of office. In Bologna, where Gavazzi preached the red democracy, anarchy was accompanied by sickening excesses.

‘For two days,’ says Farini:

The brigands had been slaughtering every man his enemy among the Government officers, some of them, indeed, disreputable and sorry fellows, others respectable. They hunted men down like wild beasts; entered their houses, and dragged them forth to slaughter. One Bianchi, an inspector of police, was lying a-bed in the last agony of consumption; they came in, set upon him, and cut his throat in the presence of his wife and children. The corpses a frightful spectacle remained in the public streets. I saw it saw death dealt about, and the abominable chase.

The Secret Societies Assassinate Count Rossi

The Pope now prevailed upon Count Rossi to become his minister. Rossi was an Italian by birth, a Liberal, an old conspirator, an old political exile; but he was an able, upright, and fearless man, and had been one of the Holy Fathers most intimate advisers ever since the beginning of the reign. A Frenchman by adoption, he had come to Rome in the time of Gregory XVI, charged by Louis Philippe to negotiate for the removal of the Jesuits from France.

He remained ther e as French ambassador till the downfall of the monarchy, and had since lived in Rome as a private citizen. The restoration of public order and the renewal of ne gotiations for the creation of an Italian confederacy were the tasks to which the Pope and the minister now applied themselves. Both objects were equally hateful to the clubs and the demagogues who had now obtained the control of the state.

‘The war of the kings is over,’ cried Mazzini; ‘the war of the peoples must now begin.’

Sterbini attacked the minister furiously in his journal, the Contemporaneo : ‘Amidst the laughter and contempt of the people he will fall.’

The 151!! of November, two months after Rossi s accession to power, was the day fixed for the opening of the Parliament. He received more than one warning that the same day had been appointed for his death.

The wife of the Minister of War wrote him that his life was to be attempted as he entered the Parliament house. A Frenchman sent him a note to the same effect.

A priest stopped him at the Quirinal and repeated the warning. The Pope had also heard rumors of the plans of the conspirators, and begged Rossi to beware. ‘They are cowards,’ replied the count; ‘ they will not dare to strike.’

But he took the precaution to post a special guard of carbineers near the Cancellaria, where the Parliament held its sessions, little thinking that the soldiers themselves had been corrupted. ‘ The cause of the Pope,’ he said to one of his colleagues, ‘ is the cause of God. I must go where my duty calls me.’

On the night before the 15th a corpse was taken from one of the public hospitals and carried secret ly to the little Capranica theatre. There a secret band of conspirators rehearsed the assassination, and the chosen instrument of the vengeance of the secret societies, a young sculptor named Santo Cosrantini, learned by repeated trials where to strike.

They were waiting for the count next morning at the entrance to the Cancellaria. When he stepped from his carriage to cross the court fierce countenances scowled upon him; hisses and angry cries assailed him. He only smiled con temptuously, and marched on.

As he reached the Staircase they gathered round him. One struck him on the side. He turned his head, and Costantini plunged a dagger into the carotid artery.

The count fell, covered with blood. Borne by one of his colleagues to the apartments of Cardinal Guzzoli hard by, he lived just long enough to re ceive absolution from a priest who was fetched in haste from a neighboring church, and so died with out a word.

The assassin and his accomplices walked away unmolested, the mob and the soldiers covering their leisurely retreat. ‘ I have still before my eyes,’ says Farini, ‘ the livid countenance of one who, as he saw me, shouted, So fare the betrayers of the people!’

All night they promenaded the city with songs of triumph. The streets were hung with flags. The bloody dagger, decked with flowers, was carried as a trophy on the top of a tricolored standard, and held up before the windows of the weeping family of the victim.

When the news of the murder committed on the stairs was carried into the Chamber of Deputies, Sterbini exclaimed : ‘ It is nothing; let us to business.’

Righetti, the deputy Minister of Finance, who witnessed the assassination, hastened to the Pope. After the first moment of agitation Pius fell upon his knees and remained some time in silent prayer.

‘ Count Rossi has died a martyr,’ said he; ‘God will receive his soul in peace.’

Insurrection in Rome

The next day the populace and the soldiers assembled together in the public squares; Sterbini and the Prince of Canino organized themselves into a ‘ provisional government’.

The diplomatic corps gathered about the Pontiff at the Quirinal; and there, soon afternoon, appeared a threatening mob to demand the surrender of all power into the hands of a ministry of the most extreme democrats headed by Sterbini, the convocation of a constituent assembly, and the immediate declaration of war against Austria.

It was the forsworn Galletti who entered the palace to announce the popular will. The Pope would not listen; but he empowered Galletti to form a cabinet.

This was not enough. The crowd set fire to the palace.

A single volley from the Swiss Guard, of whom there were about a hundred on duty, drove back the incendiaries, and the flames were extinguished. But the insurrection was fast spreading.

The people seized arms and hurried to the assault. Sharp-shooters occupied the housetops, sheltered themselves behind the fa mous equestrian groups in the centre of the square, and poured a shower of balls into the palace win dows.

Monsignor Palma, one of the papal secretaries, was killed. Bullets penetrated to the Pope’s chamber.

The Civic Guard and the Carbonari reinforced the mob. Cannon were brought up and pointed at the gates.

A deputation from the assailants announced their ultimatum; they would give His Holiness one hour to consider, at the end of which time, if their demands were not granted, they would assuredly:

Break into the Quirinal and put to death every inmate thereof, with the single ex ception of the Pope himself.

Further resistance was impossible. The Holy Father called the diplomatic corps together and told them that he must yield: ‘ But let Europe know that I am a prisoner here. I have no part in the government; they shall rule in their own name, not in mine.’

Pope Pius IX flees from Rome

SURROUNDED by spies and sentries, the Pope was in truth a prisoner. ‘ His authority is now absolutely null,’ wrote the Duke d’ Harcourt, French ambassador, ‘ and none of his acts will be free and voluntary.’

The Circolo Popolare, the most radical of the clubs, was the real government of Rome.

For some time the Holy Father had considered the advisability of flight, and he ap pears to have almost determined upon seeking refuge in France. Spain had offered him an asylum; and a safe retreat was likewise open to him in the kingdom of Naples.

But escape was not easy. He was closely watched, and guards even invaded his private apartments. On the 22nd of November, six days after the attack upon the Quirinal, he received from the Bishop of Valence, in France, a silver pyx in which Pope Pius VI used to carry the Blessed Sacrament suspended from his neck during his painful exile.

‘Heir to the name, the see, the virtues, the courage, and many of the tribulations of this great pontiff,’ wrote the bishop, ‘ you will, perhaps, attach fc-ome value to this interesting little relic, which 1 trust may not serve the same destiny in your Holiness s hands as in those o in former possessor.’ The Pope looked upon this as a providential provision for his journey, and hesitated no longer.

I was the Duke d’ Harcourt who undertook the delicate task of managing the escape from the Quirinal, while the Bavarian minister, Count Spaur, aided by his quick-witted wife, arranged the rest of the journey. The whole adventure seems to have been in great measure of the countess s designing, and our knowledge of the incidents is mainly de rived from her interesting published narrative. The Pope s faithful gentleman-in-waiting, Filippani, collected the little articles absolutely needed on the route, and at night carried them under his cloak, one by one, to the residence of Count Spaur.

Meanwhile, it was announced in Rome that the count, accompanied by his family, was going to Naples on a diplomatic errand. The countess started first in her travelling carriage with her son and his tutor, Father Liebl, giving out that her hus band, detained a few hours in Rome by important business, would overtake her at Albano.

Towards evening on the same day (November 24, 1848) the Duke d’ Harcourt visited the Quirinal in state, and, being admitted to a private official interview with the Holy Father, began to read to him a series of long despatches.

He read in a loud tone, so that his voice could be heard by the guards in the ante room. If they could have seen what passed as well as they heard, they would have been very much astonished.

For no sooner had the duke begun than the Pope retired to an inner chamber and transformed himself into a simple priest. He put on a black robe, an ample cloak, and a low, round hat, and, accompanied by Filippani, he reached the grand staircase by a private door. Twice he narrowly escaped detection.

The private door, generally left open, was found to be locked, and there was a long delay while Filippani searched for the key. As they went out a servant who was in the secret involuntarily knelt to beg the Pope s blessing, but Filippani’s whispered reproof brought him to his feet again before the guard noticed him.

There was a hack in waiting, and, exchanging salu tations with the unsuspecting soldiers, the fugitives drove to the church of SS. Peter and Marcellinus, beyond the Colosseum, where Count Spaur was waiting with another carriage.

The Pope entered it; the count took the reins; they passed out by the gate of St. John, near the Lateran, the sentries being satisfied with the count s passport; and then they sped the horses along the Appian Way.

In the meantime the Duke d’ Harcourt continued for two hours his imaginary discussion in the Holy Father’s cabinet. The private chaplain came at the accustomed hour, as if to read the breviary with His Holiness; papers were brought in as usual; supper was served; and at last it was announced to the guard that the Pope had retired for the night. Then the duke took horses in all haste for

Civita Vecchia, where a French frigate was in readiness to receive him. The first intelligence of the Pope’s flight was conveyed to the Romans by a letter received next morning by the Marquis Sacchetti from the Pope himself.

The Countess Spaur, not knowing at what hour to expect the Pope, had been waiting on the road allday in an agony of apprehension. Late in the night word was brought to her that the count was at a certain fountain on the Appian Way.

When she drove up she was terrified at finding herself in the midst of an armed patrol. Count Spaur was answering the questions of the soldiers, and the Pope and a trooper stood side by side against the fence. The countess did not lose her presence of mind.

‘Come, doctor,’ she exclaimed, ‘jump in; you have kept us waiting.’ One of the soldiers opened the carriage-door and helped the supposed doctor to mount; and, bidding good-night to the patrol, the party drove oft’ at full speed towards the territory of Naples.

The Pope was the first to speak. ‘Courage!’ said he; ‘I carry the Blessed Sacrament in the same pyx in which it was borne by Pius VI.’

At Velletri the carriage-lamps were lighted, and the Pope and Father Liebl recited the itinerarium, or prayers for a journey. The Holy Father refreshed himself with part of an orange.

In crossing the Pontine Marshes they all got a little sleep. At Fondi a postilion cried to one of his fellows: ‘Look at that priest; he is just like the picture of the Pope we have at home.’

The Pope Enters the Kingdom of Naples

They crossed the Neapolitan frontier at daylight, and as soon as they were safe beyond the Pontifical States they all recited the Te Deum.

In the afternoon they reached Gaeta, and were joined by Cardinal Antonelli, disguised like the Pope.

Count Spaur now resigned the care of the Holy Father to the secretary of the Spanish embassy, and, exchanging carriages with this gentleman, post ed on to Naples, bearing an autograph letter from the Pope to the king.

It was midnight when he presented himself at the royal palace, and, representing the urgency of his mission, obtained with some difficulty an immediate audience. King Ferdinand read with visible emotion the few lines in which the Sovereign Pontiff announced his arrival and asked a brief hospitality.

‘ Come back at daylight, count,’ said the king, ’and you shall have my answer.’

At six, accordingly, Count Spaur returned. Two frigates were in readiness in the harbor. A large body of troops were already embarked.

The king, the queen, the whole royal family were in readiness to soil with them to meet the august exile. A great store of everything necessary for the comfort and dignity of His Holi ness had been placed on board, and Ferdinand had given close personal attention to all the prepara tions. ‘ Come, count,’ said he, ‘we will go together.’

But during this interval the strange little party at Gaeta had been in trouble.

Changing carriages with the Spanish secretary, the count had also carelessly changed passports, and when the Spaniard went to call, according to the regulations of the fortress, upon the commandant, Gen. Gross, that gallant officer, who was a Swiss, addressed him in German, and the secretary could not answer.

The travellers were at once placed under polite surveil lance as suspicious characters.

They presented themselves first at the bishop’s palace, but the bishop was absent, and his servants would not admit them, notwithstanding the persistent requests of the Pope and the cardinal.

Then they took lodgings at a poor inn, and it was in this humble shelter that Pius IX wrote his first public protest against the violence which had driven him from his dominions, naming in the same document a commission to carry on the government during his absence, though with no great expectation that it would be allowed to act.

The frigate conveying the French ambassador arrived the next morning, and the king and queen landed a few hours after, to the unspeakable amazement of the commandant, who had no suspicion of the character of the visi tors he had been watching.

It had been the purpose of His Holiness to take a Spanish man-of-war at Gaeta, and seek refuge in the island of Majorca, the scene of his short im prisonment in 1823; but Ferdinand persuaded him to remain at Gaeta.

The first meeting between his Majesty and the Sovereign Pontiff took place at the palace, whither Pius IX proceeded quietly on foot, still in his humble black cassock and broad hat.

The king and queen received him on their knees at the foot of the stairs, and lavished upon him every mark of honour that it was in their power to bestow.

The palace was set apart for his use, the royal family removing to a pavilion not far distant, whence the king paid a daily visit to the Holy Father. Fitting accommodations were prepared for the cardinals and prelates who by various routes soon began to find their way to Gaeta.

The diplomatic body gathered around the improvised papal court, and naval vessels of nearly all the Christian powers, in cluding the United Sta .es, cast anchor in the road stead.

As an illustration of the respect shown to the Pontiff at Gaeta, Father Bresciani describes a papal visit to the United States frigate Princeton the king and the king’s brother following the Pope bareheaded in a hot midday sun from the palace to the port, walking deferentially behind him, refusing a seat by his side in the stern of the barge, and taking a respectful position forward, while as their boat passed all the fleet manned the yards, spread colors to the breeze, and thundered broadsides.

The reverence and affection of the whole Catholic world for the person of Pius IX seemed to be stimulated to an extraordinary degree by his misfortunes.

‘Letters were despatched to the glorious exile,’ says Father Bresciani:

From the most remote corners of the earth from the islands of Oceanica, but yesterday, as it were, converted to Chris tianity; from the Marquesas, the abode of cannibals; and from Australia and New Caledonia to comfort the Pontiff in his afflictions, to exalt him in his hu miliations, to honor him in the insults and oppro brium heaped upon him by his barbarous and cow ardly subjects in Rome. China, Tartary, the Indies, Armenia, Mesopotamia, Lebanon, Moldavia, Servia, Egypt, Algeria, the States of America from Canada to Chili, Europe from the extremity of Norway to Cadiz and Lisbon all, in every language of the world, praised and glorified the invincible Pontiff, pouring forth the veneration and love of their hearts.

The sovereigns, both Catholic and non-Catholic, wrote letters of condolence.

The people organized associations to raise funds for the Pope’s support.

On his part, Pius invoked the in terposition of the Catholic powers in general; and when the men who had driven him out of Rome sent urging him to come back on their terms, not on his he refused to see the deputation, holding then, as he did to the end of his life, that the temporal sovereignty of the Pope was necessary to the freedom and independence of the Church, and that he could not negotiate for its surrender.

Spiritual concerns were dearer to him than ever in this time of trouble. It was at Gaeta, in February, 1849, that he declared by an encyclical let ter his intention to define the dogma of the Immaculate Conception, and instructed the bishops to inform him of the feelings and opinions of the whole people with respect to it.

From his exile also he urged the bishops of Italy to fresh zeal in combatting the errors of the time by the education of the young, by preaching boldly and constantly the sound principles which lie at the basis of Christian society, by attacking prevalent vices, and showing that the Catholic faith is the true safeguard of na tional prosperity and private virtue.

To counter-act the abuses of a licentious press he exhorted them to cultivate a pure and wholesome literature and to publish approved translations of the Holy Scriptures.

And he repeated with especial earnest ness the recommendations of his first encyclical touching the training of the clergy and the disci pline of monastic establishments.

While the banished Pope was thus winning the respect of the world the miseries of his capital were almost beyond description.

The rule of the secret societies was hardly disguised by the merely nominal authority of ministries and parliamentary chambers, which one by one disappeared and left the control of affairs in the hands of a Committee of Public Safety.

A Constituent Assembly met on the jth of February, 1849, and decreed the deposition of the Popedom as a temporal government, and the establishment of ‘a pure democracy’ under ‘the glorious appellation of the Republic of Rome.’

With thousands of other republicans and members of the revolutionary clubs from different parts of the Continent, Mazzini hastened to Rome to direct the insurrection which he had been so long preparing.

An executive triumvirate was named, consist ing of Mazzini, Armellini, and Sam; but the second and third of these men counted for little, and Mazzini shared a virtual dictatorship with the military leaders, Garibaldi and Avezzana.

The catalogue of outrages committed under this democratic despotism, both in Rome and the provinces, is almost too black for belief.

‘ Every governor acted as he liked,’ says Felice Orsini, ‘and some of the Liberals took what they considered justice into their own hands and committed deplorable homicides.’

The murder of an Irish priest at last caused the British Government to interfere, whereupon Mazzini sent Orsini into the Marches to put a stop to the massacres.

‘A society of assassins afflict Ancona and Sinigaglia,’ wrote this commissioner, ‘spreading desolation and misery over the provinces.’

A secret league called the Infernal Association took upon itself the function of executing the vengeance of the societies.

A wretch named Zambianchi, leader of a band of three hundred bravos who had been employed in the revenue service of the frontier, became the terror of the provinces, boast ing of the most hideous crimes, and accounting it ample justification of a murder that the victim \vns a priest.

He stationed himself near the Neapolitan boundary, and sent back to Rome all ecclesiastics whom he caught on the road to Gaeta; but displeased that his prisoners were not immediately put to death, he soon marched into the capital to take the matter into his own hands.

The Convent of S. Calisto, in the Trastevere, became a slaughter house where he penned up priests and killed them at his leisure. How many suffered in this way can never be known.

When the triumvirate sent to stop the murders the bodies of fourteen ecclesiastics were found half buried in a garden, and twelve prisoners were rescued alive in spite of the re sistance of the butchers.

Two men clad as vine dressers were arrested one day as Jesuits in disguise, and the guards were taking them to prison when a mob attacked them on the bridge of S. Angelo and put them to a horrible death.

The pillage of private houses and the wanton destruction of public monuments were among the lesser out rages of this reign of anarchy. And the official proceedings of the Government matched the lawless violence of the populace.

Ecclesiastical property was seized, convents were suppressed. The confessionals were taken to make barricades. A forced loan was levied upon all persons whose income exceeded two thousand crowns, graduated so that no one paid less than a quarter of his income, and the rich were taxed as much as two-thirds. Silver plate was seized, and domiciliary visits were made in search of it. The shrines and altars were stripped bare. The palaces of the cardinals were sacked.

Profane rites were celebrated in St. Peter’s at Easter under the auspices of the Government, and a suspended priest gave a travesty of the papal benediction from the balcony. The canons of St. Peter’s were fined for refusing to participate in such sacrilegious proceedings, and the provost of the cathedral of Sinigaglia was put to death for declining to hail the republic by a Te Deum.

* Mr. Legge gives these particulars on the authority of Mazzini.

Buying Books at Amazon Through These Links Gives Us a Commission. This Supports Our Apostolate. Thank You if You Can Help Us Like This!

Comments

comments are currently closed

3 responses to “Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 4: Conspiracy, War and Revolution”

[…] « Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 2: The Carbonari and Other Secret Societies Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 4: Conspiracy, War and Revolution » […]

[…] It was in the mid-Nineteenth century that Bl. Pope Pius IX instituted the Feast of the Most Precious Blood of Our Lord Jesus Christ. He did so in thanksgiving for his return to Rome, having been driven out by Italian revolutionaries to Gaeta. […]

[…] Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 4: Conspiracy, War and Revolution […]