By John R. G. Hassard

Introduction:

Here is the seventh instalment of the 1878 Life of Pius IX by John R. G. Hassard – another old Nineteenth Century Catholic book in our Tridentine Catholicism Archive. (For more about this, see our introduction to the first instalment here.)

Hassard’s book appears here in nine chapters:

- Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 1: Early Years in Christendom Despoiled

- Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 2: The Carbonari and Other Secret Societies

- Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 3: The Conclave Elects a New Pope

- Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 4: Conspiracy, War and Revolution

- Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 5: Annexation of the Papal States

- Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 6: Counter-Revolution and the Syllabus of Errors

- Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 7: Ultramontanism and the First Vatican Council

- Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 8: The Seizure of Rome

- Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 9: A Prisoner of the Vatican

As this instalment opens, we are in the final years of the Papal States – before Rome is conquered by what is here referred to as the Garibaldians – or put simply the forces of the emerging Italian nation, under the command at that time of Garibaldi.

As was mentioned in the last instalment, the Pope has gathered an army – the Papal Zouaves – gathered from all corners of the Catholic world to defend Rome. The reader may be interested to see our review of a fine book about the Zoauves by Charles A. Coulombe (here) in this context.

The reader is also referred to our previous introductions in earlier instalments of this series for further background to this terrible shadow over the Papacy of Pope Pius IX.

All we will say now is that what follows is best understood in the context of the age of Ultramontanism.

Ultramontanism – the word emerged in France to describe those traditional Catholics who rejected the Revolution and felt compelled to turn their gaze from Paris towards Rome as the centre of Christendom. Rome lay beyond the mountains of the Alps, which lay between France and Italy. Hence the term, Ultramontanism – meaning beyond the mountains.

Soon, however, the word was taken up by traditional Catholics everywhere who saw the crisis of Christendom in the emerging liberal thinking – and who sought to address that crisis by turning their gaze towards Rome as the centre of Christendom.

In this era, the late 1860s, the Church was hardly divided as she tragically is today by liberal and traditional Catholics.

Rather, the scene in which the First Vatican Council unfolds is dominated by the spirit of a very largely united Ultramontanism amongst the Bishops of the world, who understand that Christendom is threatened by the new secular thinking emerging – a thinking they consider Godless and decadent – and who salute the profoundly Counter-Revolutionary measures upheld by Pope Pius IX.

We now resume our serialisation of Hassard’s book (which is likewise thoroughly pervaded by this Ultramontanist sympathy).

Rome Under Threat of Invasion

On the 6th of December, 1866, the French troops were entirely withdrawn from Rome, in accordance with the pledges of the Turin convention, and a papal army of 12,000 volunteers, recruited, like the gallant force under La Moriciere, from all the Catholic countries, and supported in great part by the special contributions of their countrymen, undertook the defence of the small remnant of the Roman territory.

La Moriciere was no longer living. General Kanzler, who had succeeded Monsignor de Merode as Minister of War, was comriiander-in-chief.

In taking leave of the French officers the Pope said: ‘We must not deceive ourselves. The revolution will come to Rome. We shall see the end here. Go, my sons, with my benediction and my love. If you see the emperor, tell him that I pray for him every day. They say that his health is not very good; I pray for his health. They say that his soul is not tranquil; I pray for his soul. The French nation is Christian; its chief ought to be Christian, too.’

To his personal friends he said: ‘ Yes, it is God who sustains his vicar. I was driven away once, and I came back. If I am driven away again I shall come back. And if I die well, if I die Peter will rise again.’

The Garibaldians, openly assisted as before by the Italian Government, hardly waited for the retirement of the French garrison before they invaded the papal territory, and Victor Emmanuel paid no more regard to the engagements of the Turin convention than if they had been made in jest.

This was more than public opinion in France would tolerate. A French force under Gen. de Failly was sent to Rome to co-operate with Gen. Kanzler; and after several minor engagements Garibaldi was signally defeated at Mentana Nov. 3, 1867, leaving a number of his men in the hands of the victors.

Fighting under no recognized flag, and repudiated by the mendacious Government at Florence, these captives were of course not entitled to be treated as prisoners of war; but the benevolent Pontiff, after visiting the wounded and supplying them with clothing, dismissed them all.

The secret societies within the city of Rome had endeavored to co operate with the invaders, and as a preliminary to the seizure of the military posts they undermined and blew up one of the barracks.

There were no soldiers in it at the time, but the musicians of the Zouave corps were there practising, and they lost their lives by the explosion. Two of the authors of this atrocious deed were arrested, tried by the civil courts, and executed.

The moment the Garibaldians crossed the frontier, and even before there had been any serious passage of arms, Count Giraud, one of the municipal councillors of Rome, accompanied by thiee of his colleagues, all Liberals like himself, waited upon the Pope and asked leave to present a petition which the municipal council had been charged to submit to the Vatican.

It was a request that His Holiness would invite Victor Emmanuel to occupy Rome with an army, in order to maintain order, and it professed to be supported by the signatures of 12,000 Roman citizens. Pius, having received the deputation and read the petition, asked for the roll of signatures.

The count was disconcerted, and at last acknowledged that the petition was anonymous, and had been given to him by a porter, who had received it in the street from an unknown gentleman. The 12,000 Roman citizens had no existence in the flesh.

The Pope dismissed the abashed deputation, and said to those around him: ‘ I shall not open the gates of Rome to the troops of Victor Emmanuel any more than to the troops of Garibaldi; and those who enter will enter by violence. If they are the royal troops who seize upon my capital I shall quit the city; but if they are the Garibaldians I shall remain to share with my clergy the martyrdom which awaits us.’

Ultramontanism in Full Force: The Centenary of St Peter

It was in the midst of mutterings of revolution and threats of exile that Pius summoned around his throne, for the third time, a mighty assemblage of the bishops of the world.

Two days after the departure of the French garrison, when he found himself almost defenceless, face to face with the enemy which had been pressing upon him for twenty years, he issued the letters of invitation -which called the whole episcopate to Rome For the celebration of the eighteenth centenary of the martyrdom of St. Peter.

The anniversary fell in June, 1867. To human judgment it appeared in the highest degree improbable that a concourse of bishops would be allowed to meet at the tomb of the apostle in June, 1867, and doubtful whether the Pope himself would be in Rome.

But to the sublime faith of Pius IX no difficulties seemed alarming. At the appointed time such a spectacle was witnessed in the capital of Christendom as the world had never seen before.

Five hundred and twelve bishops, twenty thousand priests, and one hundred and twenty thousand other persons flocked to Rome for this extraordinary solemnity. The population of the city was doubled.

Pilgrims from the four quarters of the earth brought rich offer ings. The signatures to addresses counted by mil lions. The Italians, who were said to be hostile to the Papacy, were no less enthusiastic than other nations in commemorating the first Pope and honoring his living successor. A hundred cities of Italy united in presenting an enormous album and a hundred purses of gold.

Fifty thousand Italians from various parts of the peninsula are said to have joined the universal pilgrimage. America and the Indies sent their thousands.

‘The patriarchs and bishops of the East who surrounded Pius IX,’ said Cardinal Manning, ‘brought to my mind the first-fruits of the nations who came up to Bethlehem. There were some who had travelled forty days one who had travelled longer still before they could reach an ordinary road. When I saw them surround the vicar of our Lord and kiss his feet, almost by force, I prayed God that the day migr.t be hastened when the sun shall arise upon Asia re stored to the unity of the only fold.’ Eighty-fir-; of the poorest of the bishops were lodged and enter tained at the Pope s expense, and not one of thest needy prelates was dismissed without a handsome present for his diocese.

For three weeks Rome was filled with the aroma of piety, the flame of religious ardor, and the splendor of stately ceremonial. So grand a mani festation of the universality of the Church, so impres sive an evidence of the union between the bishops and their chief, will long be chronicled in sacred history as one of the momentous events of our stirring time.

Pius IX on the Crisis of Christendom

The lyth of June was the anniversary of the Pope’s creation. After the Mass in the Sistine the Holy Father went to unvest in the Pauline Chapel, and there the cardinal-vicar, in the name of the Sacred College, made the usual address of congratulation, wishing his Holiness ‘health and many years to see the peace and triumph of the Church.’

The beautiful and touching language in which Pius replied is said to have stirred the heart of every one present:

I accept your good wishes from my heart, but I remit their verification to the hands of God.

We are in a moment of great crisis. If we look only to the aspect of human events, there is no hope; but we have a higher confidence.

Men are intoxicated with dreams of unity and progress; but neither is possible without justice. Unity and progress based on pride and egotism are illusions.

God has laid on me the duty to declare the truths on which Christian society is based, and to condemn the errors which undermine its foundations.

And I have not been silent.

In the encyclical of 1864, and in that which is called the Syllabus, I declared to the world the dangers which threaten society, and I condemned the falsehoods which assail its life.

That act I now confirm in your presence, and I set it again before you as the rule of your teaching.

To you, venerable brethren, as bishops of the Church, I now appeal to assist me in this conflict with error. On you I rely for support.

When the people of Israel wandered in the wilderness they had a pillar of fire to guide them in the night, and a cloud to shield them from the heat by day. You are the pillar and the cloud to the people of God.

By your teaching you must guide the faithful in the darkness; by your example you must shield them from the burning sun of this world.

I am aged and alone, praying on the mountain; and you, the bishops of the Church, are come to hold up my arms.

The Church must suffer, but it will conquer. Preach the word; be instant in season, out of season; reprove, entreat, rebuke with all patience and doctrine.

For there shall be a time and that time is come when they will not endure sound doctrine. The world will contradict you and turn from you; but be firm and faithful.

For I am even now ready to be sacrificed, and the time of my dissolution is at hand. I have, I trust, fought a good fight, and have kept the faith; and there is laid up for you, and I hope for me also, a crown of justice which the Lord, the just judge, will render to me at that day!

The 2oth of June was the feast of Corpus Christi; as the Supreme Pontiff knelt on that day with the Blessed Sacrament in his hands, praying silently in the midst of the silent multitude, with half the bishops of the universe around him, an eye-witness of the ceremony relates that a calm so profound fell upon the immense gathering that one seemed to be alone in the stillness of the desert.

On the 24th, when the Pope visited the Lateran basilica, a vast crowd in the great square before the church rent the air with acclamations so long and hearty that the Holy Father, no stranger certainly to marks of popular affection, was moved to tears.

The papal carriage, surrounded by an excited populace cheering, waving handkerchiefs, and scat tering flowers, was for some time unable to move, and the demonstrations lasted all through the journey of three miles from the Lateran to St. Peter s. It is related that by the time the Pope reached the Vatican his white cloak was torn almost to shreds by relic-hunters.

First Announcement of the Vatican Council

On the 26th was held a consistory in the tribune over the atrium of St. Peter’s, and there Pius IX made the first public announcement of his intention to summon an oecumenical council. On the eve of the Centenary the Pope sang Vespers with great solemnity in St. Peter s. At night the city was illuminated.

The pontifical Mass, on the feast itself (June 29), was celebrated by the Holy Father at the high altar of St. Peter s, over the apostle’s tomb, and after the gospel he preached a sermon to the five hundred bishops and the innumerable multitude of the faithful who filled the basilica.

‘The splendour and beauty of that ceremony,’ says Cardinal Manning, ‘was probably never equalled. It was royal and pontifical in all the fulness of majestic grandeur.’

The episcopal chair of St. Peter, which is enclosed within a bronze throne designed by Bernino and placed above the altar in the apse of the church, was exposed to view for the first time in two hundred years.

Other incidents of the prolonged commemoration were the celebration of the feast of St. Paul in the gorgeous basilica outside the walls; the consecration of the church of St. Mary of the Angels; and, lastly, on the 1st of July the reception of the bishops, who presented a reply to the allocution.

Says Cardinal Manning:

When the address had been read and when the Holy Father was about to bestow the apostolical benediction and bid farewell to the bishops, the Angelus of noon sounded. He rose and began the Angelical Salutation, half the bishops of the world responding.

Such a salutation was perhaps never before offered to the Mother of God on earth. At Enhesus there were four hundred and thirty bishops, but the Vicar of her divine Son was not there. So, simply and grandly, ended the Centenary of 1867.

The announcement of the coming council was a great surprise to nearly all those present at the Centenary, and it was received with unbounded satisfaction.

On Papal Infallibility

Although it was certainly not the purpose of the Sovereign Pontiff to obtain from this oecumenical gathering a definition of any one particular doctrine, the dogmatic declaration of Papal Infallibility, which the events of the past ten or twelve years had been forcing more and more upon the attention of the episcopate, was at once made a subject of discussion, and most theologians probably saw that it must logically follow from an assembling of the council.

After the allocution of the 26th of June a general meeting of the bishops was held at the Altieri Palace to draw up the address of reply. The task was delegated to a committee of seven, consisting of Cardinal de Angelis, the Archbishops of Saragossa, Sorrento, and Kalocsa, Monsignor (now Cardinal) Franchi, Dr. Manning, and Bishop Dupanloup. Dr. Manning relates that in the original draft of the address the word ‘infallible’ was in more places than one ascribed to the office and authority of the Pontiff.

To this word, as expressing a doctrine of Catholic truth, no member of the commission objected. It was urged, however, that the term had never yet been applied to the Pope in the formal acts of any general council, and, as the five hundred bishops then assembled in Rome did not constitute a coun cil, it might be advisable not to forestall the future action of the episcopate by adopting any language not already sanctioned by the authoritative decla rations of the Church,

The address was restricted, therefore, to the expressions used by the Council of Florence (1439). How plainly it implied the doctrine of infallibility and foreshadowed the definition of 1870 will be seen from the following extract:

Five years ago we rendered our due testimony to the sublime office you bear, and gave public expression to our prayers for you, for your civil princedom, and the cause of right and of religion.

We then professed, both in words and writing, that nothing was more true or dearer to us than to believe and teach those things which you believe and teach, than to reject those errors which you reject. All those things which we then declared we now renew and confirm. Never has your voice been silent.

You have accounted it to belong to your supreme office to proclaim eternal verities, to smite the errors of the time which threaten to overthrow the natural and super natural order of things and the very foundations of ecclesiastical and civil power; so that at length all may know what it is that every Catholic should hold, retain, and profess.

Believing that Peter has spoken by the mouth of Pius therefore whatsoever you have spoken, confirmed, and pronounced for the safe custody of the deposit we likewise speak, confirm, and pronouncc; and with one voice and one mind we reject everything which, as being opposed to divine faith, the salvation of souls, and the good of human society, you have judged fit to reprove and reject.

For that is firmly and deeply established in our consciousness which the fathers at Florence defined in their decree on Union, that the Roman Pontiff is the vicar of Christ, head of the whole Church, and father and teacher of all Christians; and that to him, in the person of blessed Peter, has been committed by our Lord Jesus Christ full power to feed, to rule, and to govern the universal Church!

‘The Universal Suffrage of Christendom’

The 11th of April, 1869, was the fiftieth anniversary of the Pope’s first Mass, and his ‘golden jubilee ‘was celebrated all over the world with extraordinary demonstrations of regard. The sovereigns of Europe sent him autograph letters of congratulation.

The people made offerings of money and other valuable presents, and deputations from distant countries travelled to Rome to make a personal protestation of loyalty and affection.

Never before, said a German archbishop in a pastoral letter on this occasion, has any pope been brought so close to the universal heart of humanity.

‘Ah! my God,’ exclaimed the Holy Father, in replying to an address by certain pilgrims, ‘ have mercy on me; my happiness is too great. I fear lest, when I appear before thy justice, thou mayest say to me, Thou hast had thy reward on earth. No, it is not for me, O my God; the love of these Christians is for thee for thee alone!’

The costly tributes presented to the Holy Father at this jubilee were publicly displayed in the halls of the Vatican.

As Pius walked with his guests, ‘Here,’ said he, ‘ is my Exhibition. And here,’ laying his hand upon the mighty pile of signed addresses, ‘is the universal suffrage of Christendom.’

‘The Disorders of the World … Call for Correction by a General Council’

I have mentioned in the proper place the first public announcement of the intention of Pius IX to summon an ecumenical council. But the project had been for a long time under serious consideration.

I have mentioned in the proper place the first public announcement of the intention of Pius IX to summon an ecumenical council. But the project had been for a long time under serious consideration.

On the 6th of December, 1864, the Pope presided in the Vatican palace over a session of the Congregation of Rites, composed of cardinals and officials. After the opening prayer the officials were requested to retire, and the cardinals remained for some time in secret conference with the Pontiff.*

This unusual event caused great surprise and curiosity. It was not known until long afterward that the Holy Father had communicated to the Sacred College the thought, which had been for some years in his mind, of convoking a council ‘as an extraordinary remedy to the extraordinary needs of the Christian world,’ and had required from each of the cardinals then in Rome a written opinion on the subject.

Twenty- one answers were submitted in due time to this command.

All except two agreed that the disorders of the world: the tendency to exclude the Church and revelation from the sphere of civil society and science; the progress of ‘modern revolutionary liberalism,’ which consists in the assertion of the supremacy of the state over the spiritual jurisdiction of the Church, over education, marriage, consecrated property, and the temporal power of the head of the Church; the spread of indifferentism; the infiltration of rationalistic principles into the philosophy of certain Catholic schools; and changes made necessary in Church discipline by changes in the general condition of society during the three hundred years since the Council of Trent, did call for correction by a general council.

Four of the cardinals doubted whether the time was convenient for the assembling of a council, but they believed that all the preparations ought to be made for it. One declined to express a positive opinion, submitting himself to the judgment of the Pontiff.

Only two opposed the project. The majority foresaw many difficulties, but they held that the need was greater than the danger.

With regard to the subjects to be treated, the cardinals suggested the condemnation of modern errors, the exposition of Catholic doctrine, the observance and modification of discipline, the raising of the state of the clergy and the religious orders, the license of the press, secret societies, marriage, etc. Only two spoke of infallibility. Only two spoke of the temporal power. Only one spoke ot the Syllabus.

The next step was the appointment in March, 1865, of a commission, composed of Cardinals Patrizi, Reisach, Panebianco, Bizzarri, and Caterini, to weigh all these written opinions, to consider still more carefully the reasons for and against the con vocation, and to advise upon the proper mode of proceeding in case the decision should be in the affirmative.

The commission judged that the assembling of a council was ‘relatively necessary and opportune, and that a Congregation of Direction ought to be appointed to report upon tin; questions, whether of doctrine or discipline, proper to be treated.

In accordance with this recommendation the congregation was accordingly con stituted of the five cardinals already named and a number of theologians and canonists selected in Rome and from other nations; and the whole body was divided into four sections, each having its own class of subjects namely:

- 1. Doctrine;

- 2. Political, Ecclesiastical, or Mixed Questions;

- 3. Missions and the Oriental Churches;

- 4. Discipline.

In April, confidential letters were: addressed to thirty-six bishops in Europe, selected for their learning and experience, and also to certain bishops in the East, asking their opinions as to the proper matters to be treated.

In the Age of Ultramontanism

Nearly all replied that the prevalent evil of our time is a universal perversion and confusion of first truths and principles which assail the foundations of truth and the preambles of all belief.

They spoke of the nature and existence of God; the divine institution, rights, independence, and authority of the Church; the temporal power; socialism, communism, indifferentism, naturalism; Christian marriage; the relations of Church and state, etc.

Many proposed the Syllabus as an admirable outline of the work of a council. One and all expressed the greatest delight at the decision to call a council; but the chief object for which Protestant writers believe the fathers of the world were to be assembled namely, the definition of papal infallibility was hardly so much as mentioned.

Says Cardinal Manning:

The true motive of the Vatican Council is transparent to all calm and just minds. For three hundred years no general council had been held; for three hundred years the greatest change that has ever come upon the world since its conversion to Christianity had steadily passed upon it.

The first period of the Church gradually brought about the union of the spiritual and civil powers of the world in amity and co-operation.

The last three hundred years have parted and opposed them to each other . . .

The Church began not with kings but with the peoples of the world, and to the peoples, it may be, the Church will once more return.

The princes and governments and legislalatures of the world were everywhere against it at its outset; they are so again.

But the hostility of the nineteenth century is keener than the hostility of the first. Then the world had never believed in Christianity; now it is falling from it.

But the Church is the same, and can renew its relations with whatsoever forms of civil life the world is pleased to fashion for itself.

If, as political foresight has predicted, all nations are on their way to democracy, the Church will know how to meet this new and strange aspect of the world.

The high policy of wisdom by which the pontiffs held together the dynasties of the Middle Age will know how to hold together the peoples who still believe. Such was the world on which Pius IX was looking out when he conceived the thought of an ecumenical council.

He saw the world which was once all Catholic tossed and harassed by the revolt of its intellect against the revelation of God, and of its will against his law; by the revolt of civil society against the sovereignty of God; and by the anti-Christian spirit which is driving on princes and governments towards anti-Christian revolutions.

He to whom, in the words of St. John Chrysostom, the whole world was committed, saw in the Council of the Vatican the only adequate remedy for the world-wide evils of the nineteenth century.’

The question of calling a council being decided, it remained to determine whether in the existing condition of politics its speedy convocation would be prudent.

In November, 1865, the Holy Father asked the advice on this head of the nuncios at Paris, Vienna, Madrid, Munich, and Brussels; and if the times had been favorable it was his intention to open the august assemblage on the centenary of St. Peter, in June, 1867.

But the war between Austria and Prussia caused all the preparations to be suspended.

No allusion was made to the council in the letters of invitation to the centenary; and when it was at last announced in the con sistory of June 26, 1867, the date was still undetermined.

The First Vatican Council is Convoked

A year later, Pius IX consulted the cardinals as to the expediency of fixing the opening for the 8th of December, 1869, and by their unanimous advice the bull of indiction, convoking the council for that day, was issued on the feast of SS. Peter and Paul, June 29, 1868.

It has already been remarked that the formal definition of the infallibility of the Pontiff followed logically from the tendencies of the past few years, and especially from the circumstances at tending the three previous assemblies of bishops held in Rome during the pontificate of Pius IX.

But if the desires of the believers in the doctrine had not been enough to ensure its promulgation, the opposition of its adversaries would certainly have sufficed for that result.

In France the last remnant of the Gallican sentiment found expression in the publications of Bishop Maret, the Abbe Gratry, and some others, while Bishop Dupanloup led a small party which, without questioning the truth of the doctrine, remonstrated against the policy of defining it.

The centre of opposition to the dogma was, however, in Munich, where Dr. Dullin- ger was the head of an unfaithful school which Pius had already marked with the censure of the supreme authority.

The anonymous treatise by ‘Janus’ on The Pope and the Council appeared from this source in 1868, and made a profound sensation all over the continent.

It attacked the doctrine with historical arguments, and it first put forth the fiction, afterwards repeated by all the anti-Catholic press with its million tongues, that the sole purpose of the council was to declare papal infallibility by acclamation, and that the moving spirit behind it was a Jesuit conspiracy.

Conferences were held in France, Belgium, aid Germany to organize an opposition. The secular governments were drawn into the plot. In April, 1869, a circular despatch, prepared by Dr. Dollinger, but signed by the Bavarian minister, Prince Hohenlohe, invited the other European powers to combine with Bavaria in resistance to the defini tion.

Italy, by its diplomatic agents, urged the governments to prevent the assembling of the council.

Spain threatened the Pope with a hostile league composed of France, Italy, Spain, Portugal, and Bavaria.

Finally, Italy and Bavaria united in a request to the French Government to with draw its troops from Rome, ‘in order to ensure the freedom of the council’ – in other words, in order to let Victor Emmanuel seize the city.

An anonymous argument against the opportuneness of defining the papal infallibility appeared in five languages, and was distributed to the bishops by the civil authorities. The newspapers of every country and of every shade of belief, except the true one, began to assail the council in advance.

The effect of this widespread conspiracy against the definition was to make its adoption certain.

Says Cardinal Manning:

It was seen at once that not only the truth of a doctrine but the independence of the Church was at stake. If the Church should hesitate or give way before an opposition of newspapers and of governments, its office as witness and teacher of revelation would be shaken throughout the world.

The Commission of Direction consisted of five cardinal presidents, eight bishops, and an arch bishop as secretary. To it were joined one hundred and two consultors, of whom sixty-nine were secular priests, eight Jesuits, four Dominicans, two Augustinians, and the rest members of other religious orders or congregations.

This commission drew up the rules of proceeding, but they were published on the authority of the Pope, the consultors deciding that the regulation of the council belonged to the power which convened it.

The commission then prepared schemata or drafts of such decrees as it proposed for discussion; it was provided that any bishop desiring to introduce other matter should submit it first to a special commission of twenty- six, whose judgment required the ratification of the Pontiff.

The decrees drawn up in advance were six namely:

- 1. Schema on Catholic Doctrine against the manifold errors flowing from rationalism;

- 2. Schema on the Church of Christ;

- 3. Schema on the Office of Bishops;

- 4. Schema on the Vacancy of Sees;

- 5. Schema on the Life and Manners of the Clergy;

- 6. Schema on the Little Catechism.

The Pope was careful to explain to the bishops by his formal apostolic letter that he had abstained from giving these drafts or schemata any sanction; they were submitted for unrestricted discussion, and might all be rejected if the fathers thought fit.

Careful arrangements were made to secure the greatest freedom of debate, and tie most minute examination both of the original sche mata and of whatever amendments might be suggested, every point being fully considered both in the general congregation of the bishops and in the appropriate committees.

The committees, or ‘deputations,’ as they were called, were six in number namely:

1. On excuses for non-attendance and for leave of absence, 5 members;

2. Grievances and complaints, 5 members;

3. Faith, 24 members;

4. Discipline, 24 members;

5. Regular orders, 24 members;

6. Oriental rites and missions, 24 members.

Each of the last four had a cardinal for president, named by the Pope; the members went elected by ballot in the full council.

The mos important committee was that on Faith; Cardinal Bilio was chairman, and the members comprised 3 bishops from Italy, 2 from France, 2 from Spain, 2 from the United States (Baltimore and San Francisco), 2 from South America, one each from England, Ireland, Hungary, Poland, Austria, Holland, Belgium, Bavaria, Prussia, Switzerland, and India, and the Armenian patriarch.

The First Vatican Council Opens

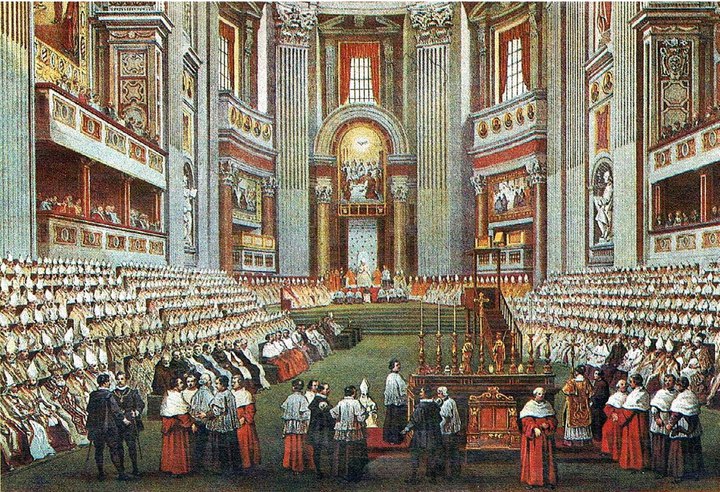

On the 8th of December, 1869, the Council of the Vatican opened with magnificent ceremony.

The number of the fathers present was seven hundred and twenty-two ** namely, 49 cardinals, 9 patriarchs, 4 primates, 123 archbishops, 480 bishops, 28 abbots, and 29 chiefs of religious orders.

Rain fell in torrents, but from an eaily hour in the morning the church and square of St. Peter were filled with visitors from all parts of the earth, and several royal personages were among the privileged spectators. The sessions were held in the right-hand transept of St. Peter s, which had been divided from the body of the church by a massive partition. Mass was celebrated by Cardinal Patrizi, the Veni Creator was sung, and the Holy Father made a short address.

Thus began the momentous deliberations which, prolonged for more than eight months, were to mark this age, as the Council of Nicaea and the Council of Trent now mark in history the fourth and the sixteenth centuries.’

The business of the council was transacted in private, and the fathers were pledged to secrecy; but the newspaper press was soon filled with the most exciting reports of scenes within the sacred hall, quarrels among the bishops, and violent attempts of the partisans of infallibility to stifle free discus sion.

The Augsburg Gazette in particular became the receptacle of torrents of mendacity, which were thence distributed all over the world.

The most important of the innumerable falsehoods were exposed fiom time to time by certain of the bishops and the world has now nearly forgotten them.

Whatever vitality they may have retained has perhaps been destroyed by the True Story of Cardinal Manning, who was:

enabled to attend, with the exception of about three or four days, every session of the council, eighty-nine in number, from the opening to the close,’ and who bears the most im pressive testimony to the ‘calmness, self-respect, mutual forbearance, courtesy, and self-control ‘ of the venerable assembly, the absolute freedom an I great fulness of the debates, and the spirit of cha rity and devotion which filled the entire body.

A fair idea of the thoroughness of the discussions given by Cardinal Manning‘s detailed account of the passing of the first decree, on the Catholic Faith. The original schema was entirely remodelled, ther amended six times in its new shape, referred again and again from general congregation to committee, and from committee back again to general congregation, and finally adopted unanimously after 364 separate amendments had been examined and voted on, and four months time had been spent in the labor.

The first dogmatic constitution, Of the Catholic Faith was thus formally adopted in the third ‘public session ‘ of the council, April 24, 1870, when 667 votes were cast.

In preparing the second schema, On the Church of Christ, the Commission of Direction was obliged to consider the question of infallibility, and on the 11th of February, 1869, it reached the questions, first, ‘whether the infallibility of the Roman Pontiff can be defined as an article of faith’; and, secondly, ‘whether it ought to be defined.’

To the first the commission replied unanimously in the affirmative. Respecting the second they decided, with one dissenting voice, ‘that this subject ought not to be proposed by the Apostolic See except the petition of the bishops.’

When the schema on the Church was introduced, therefore, it contained no definition of the doctrine of infallibility.

But a large majority of the bishops believed that the definition was necessary in view of what had taken place outside the council, and they consequently resorted to the regular course of presenting a peti tion to the Commission of Postulates, asking that a chapter on the subject of infallibility should be added to the schema.

The petition, drawn up by a few of the bishops in an informal meeting, re ceived four hundred and fifty signatures. In the meantime the opposition circulated a petition against the introduction of the subject, and this re ceived about one hundred names. Both sides gave a summary of their reasons.

Says Cardinal Manning:

Once for all let it be said that the question whether the infallibility of the head of the Church be a true doctrine or not was never discussed in the council, nor even proposed to it. The only ques tion was whether it was expedient, prudent, season able, and timely, regard being had to the condition of the world, of the nations of Europe, of the Christians in separation from the Church, to put this truth in the form of a definition.

A grave injustice has been done to the bishops who opposed the definition. The world outside the Church, not believing in infallibility, claimed them as its own. They were treated as if they denied the truth of the doctrine itself. Their opposition was not to the doctrine, but to the defining of it; and not even absolutely to the defining of it, but to the defining of it at this time . . .

They who were in the coun cil may be permitted to bear witness to what they heard and know. Not five bishops in the council could be justly thought to have opposed the truth of the doctrine. This is the testimony of one who heard the whole discussion, and never heard an explicit denial of its truth.

The petitions were duly presented to the Commission of Postulates on the 9th of February, 1870, and the commission decided, with hardly any dissent, that a new chapter on infallibility should be introduced. The petition of the four hundred and fifty had been immediately printed in the Augsburg Gazette, and a storm of opposition broke forth.

The French Minister of Foreign Affairs on the 2oth of February addressed to Rome a diplomatic protest against the declaration, alleging that it involved the extension of infallibility to facts of history, philosophy, and science external to revelation, as well as the absolute subordination to ecclesiastical au thority of the constituent principles of civil society, the rights and duties of citizenship, and in general all the rights of the state; and he asked ‘how it could have been imagined that princes would lower their sovereignty before the supremacy of the court of Rome.’

Cardinal Antonelli, in answering this extraordinary communication, exposed its misrepre sentations of the character and significance of the proposed definition, and pertinently reminded the count that the doctrines of which he complained were no more than the exposition of the maxims and fundamental principles of the Church, repeated over and over again in bulls, pontifical constitutions, and the acts of councils, taught in all Catholic schools and defended by a host of ecclesiastical writers.

One day, when the clamour against the council was at its height, the Holy Father said: ‘ I have just been warned that if the council persist in making this definition the protection of the French army will be withdrawn.’

And then after a pause he added, with great calmness: ‘As if the unworthy Vicar of Jesus Christ could be swayed by such motives as these!’

The new chapter on infallibility was distributed to the council on the yth of March, and eighteen days were allowed for the submission of amendments. The general discussion on the schema of the Primacy, whereof the question of infallibility formed the fourth chapter, did not begin until the 14th of May, and it lasted through fourteen sessions. By that time sixty-four had spoken; the argument was evidently exhausted, and the opposition began to appear factious.

According to the regulations of the council, the presiding cardinal, on the petition of ten bishops, might take the sense of the whole body whether the discussion should close.

A petition signed not by ten, but by ten or fifteen times ten, was made to this end, and the general debate was stopped by the vote of an immense majority.

Then came the special discussions on the introduction to the schema and on each of its four chapters. The fourth chapter, on infallibility, was reached on the 15th of June, and occupied eleven sessions, during which fifty-seven bishops spoke and ninety-six amendments were offered. After all the chapters had been adopted singly the wholi schema was put to the decisive vote on the 13th of July. There were 601 fathers present; 451 voted placet or ‘ay’; 88 non placet, or ‘no’; and 6: placet juxia modum, or ‘ay, with modifications.’

This involved the examination of more written amendments, to the number of one hundred and sixty-five, and on the 16th the schema was again put to the vote and passed.

Proclaiming the Dogma of Papal Infallibility

It remained now to formally promulgate the decree in public session. There were many reasons why this last act in the great work should be hastened. A number of the bishops had been compelled by illness to return home; others were sick in Rome; the summer heats were severe and dan gerous; more than all, the political situation was full of menace, the definitive rupture between France and Prussia having occurred on the 14th of July, when both Powers recalled their ambassadors.

On the 15th the Archbishop of Bordeaux waited upon the Holy Father to beg, in the name of several of the French prelates, that he would complete the definition at once. On the stairs he met the Primate of Hungary, with the archbishops of Paris, Munich, and Milan, the Bishop of Dijon, and Bishop Ketteler of Mayence, who came to petition for a delay or a modification of the decree, which they still regarded as inopportune in the ex isting condition of society.

This double demonstration must have convinced the Holy Father, if perchance he was in doubt, that the controversy ought to be promptly closed. He replied that the circumstances would not admit of delay, and that modifications were impossible.

The 18th was accordingly appointed for the fourth public session of the council and the promulgation of the dogmatic constitution ‘ Of the Church of Christ,’ including the infallibility of the Pontiff.

On the previous evening fifty five bishops of the opposition, un willing to assent to the prudence or usefulness of the definition, but still not attacking the doctrine, signed a paper announcing their intention not to appear at the public session. It was believed that they left Rome.

The fathers assembled at nine o clock on the morning of the 18th in the hall of the council, whose wide doors on this occasion, as at the other public sessions, were thrown open. Mass being over, the Pope entered, attended by the officers of his court, and took his place on the throne. The customary prayers and the Litany of the Saints were chanted. The Veni Creator was sung by the fathers and people together. Then the dogmatic consti tution was read aloud, closing with these words:

We teach and define it to be a doctrine divinely re vealed that when the Roman Pontiff speaks ex cathedra that is, when in the exercise of his office of pastor and teacher of all Christians, and in virtue of his supreme apostolical authority, he defines that a doctrine of faith or morals is to be held by the universal Church he possesses, through the divine assistance promised to him in the Blessed Peter, that infallibility with which the divinu Redeemer wished his Church to be endowed in defining a doctrine of faith or morals; and, therefore, that such definitions of the Roman Pontiff are irreformable o;’ themselves, and not from the consent of the Church.

The name of every bishop was called in turn; 535 were present; 533 voted placet; 2 only voted non placet.

As the roll began, a furious storm burst over Rome, and peals of thunder mingled with the declarations of the fathers.

The Pontiff confirmed the decree in the usual form, whereat there rose from the lips of the bishops within the hall and the multitude in the open church a murmur of approbation which swelled by degrees to a shout of ‘Viva Pio Nona, Papa infallibile!’

In a short allocution the Holy Father prayed that the few who had been of another mind in the time of storm might, in a season of calm and ‘in the gentle air,’ be reunited to the great majority of their brethren. His prayer was granted.

All the bishops of the opposition gave their adhesion to the decree, and the schism of the ‘ Old Catholics,’ under Dr. Dollinger, was of too little consequence to be counted a misfortune, except for the handful of disaffected philosophers who took part in it.

The session closed with the Te Deum, in which the chorus of the populace drowned the voices of the papal choir.

The work of the council was not complete; but the inconveniences of a longer stay in Rome were so serious to most of the bishops that the sessions were prorogued for the rest of the summer. Before the holiday came to an end the Pope ceased to be master of Rome, and the council, never dissolved, has never yet been able to reassemble.

* See The True Story of the Vatican Council, by Cardinal Manning (London 1877). I have drawn the history of the council almost en tirely from this admirable little book. 182

** The number rose afterwards to 766 – 541 from Europe, 114 from America, 83 from Asia, 14 from Africa, 14 from Uceamca.

Buying Books at Amazon Through These Links Gives Us a Commission. This Supports Our Apostolate. Thank You if You Can Help Us Like This!

Comments

comments are currently closed

One response to “Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 7: Ultramontanism and the First Vatican Council”

[…] Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 7: Ultramontanism and the First Vatican Council […]