By John R. G. Hassard

CJS.org Introduction

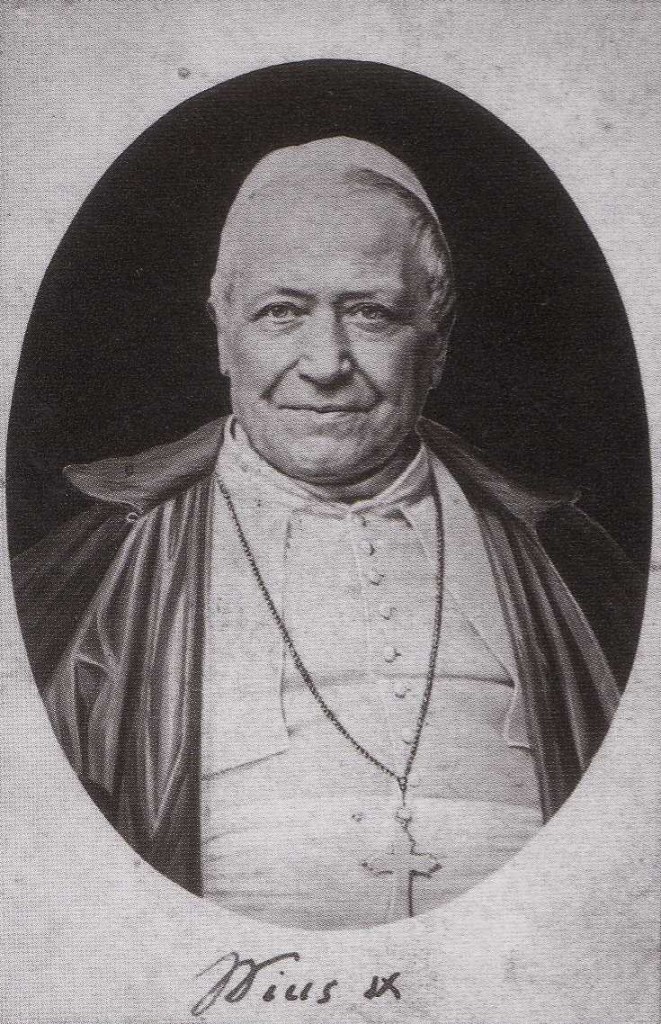

Here is the fifth instalment of the 1878 Life of Pius IX by John R. G. Hassard – another old Nineteenth Century Catholic book in our Tridentine Catholicism Archive. (For more about this, see our introduction to the first instalment here.)

Hassard’s book appears here in nine chapters:

- Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 1: Early Years in Christendom Despoiled

- Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 2: The Carbonari and Other Secret Societies

- Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 3: The Conclave Elects a New Pope

- Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 4: Conspiracy, War and Revolution

- Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 5: Annexation of the Papal States

- Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 6: Counter-Revolution and the Syllabus of Errors

- Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 7: Ultramontanism and the First Vatican Council

- Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 8: The Seizure of Rome and the Last Stand of the Papal Zouaves

- Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 9: A Prisoner of the Vatican

In this instalment, we have to do with the restoration of the Pope’s rule over Rome, as well as the beginning of the process whereby the Papal States were slowly annexed and conquered.

As indicated in previous instalments, this occupation of the Papal States was part of the Risorgimento – the process of Italian unification.

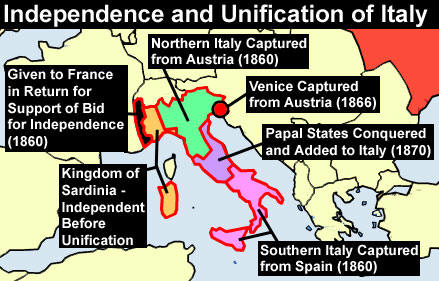

The following map (that we have featured before) provides a version of that process that is somewhat simplified.

To give an example of this simplification, the map simply notes ‘Papal States conquered and added to Italy (1870).’

However, the 1870 date only marks the completion of the process. The conquest, as we shall see below, began in 1860.

The reader who is unfamiliar with the Risorgimento should note that the orange areas which are described as the Kingdom of Sardinia are also known as Sardinia-Piedmont. And to make matters more confusing, Hassard often calls this kingdom simply Piedmont! Thus Sardinia and Piedmont can be read interchangeably in much of what follows.

Yet another simplification is that the map does not show the smaller duchies of Tuscany (with Florence) and Parma – mentioned in the text below – which were also annexed to Sardinia- Piedmont – along with the Papal States.

We are trying to give a simple, accessible version of a complex history here. For whilst it was a recent and familiar history to many at the time that Hassard wrote his book (in 1878) much has now been forgotten by many people today.

In previous instalments, we have suggested that the interested reader may profitably consult Wikipedia to gain a clearer understanding of the issues involved.

At the same time, we have suggested that Wikipedia often carries its own bias – the bias of modern, secular liberal historiography. And we have noted that Hassard is not without bias either – he is clearly an apologist for Bl. Pius IX.

To illustrate what we mean, let us quickly reference Wikipedia‘s description of some of key events in Italian history relevant to what follows:

In 1848, nationalist and liberal revolutions began to break out across Europe; in 1849, a Roman Republic was declared and the hitherto liberally-inclined Pope Pius IX had to flee the city.

The revolution was suppressed with French help in 1850 and Pius IX switched to a conservative line of government.

As a result of the Austro-Sardinian War of 1859, Sardinia-Piedmont annexed Lombardy, while Giuseppe Garibaldi overthrew the Bourbon monarchy in the south.

Afraid that Garibaldi would set up a republican government, the Piedmont government petitioned French Emperor Napoleon III for permission to send troops through the Papal States to gain control of the south. This was granted on the condition that Rome be left undisturbed.

In 1860, with much of the region already in rebellion against Papal rule, Sardinia-Piedmont conquered the eastern two-thirds of the Papal States and cemented its hold on the south.

Bologna, Ferrara, Umbria, the Marches, Benevento and Pontecorvo were all formally annexed by November of the same year. While considerably reduced, the Papal States nevertheless still covered the Latium and large areas northwest of Rome

A unified Kingdom of Italy was declared and in March 1861, the first Italian parliament, which met in Turin, the old capital of Piedmont, declared Rome the capital of the new Kingdom [Italics mine]

The careful reader will note that Wikipedia‘s account has a hermeneutic rejected by Hassard.

For example, Hassard challenges or at least nuances the now-commonly accepted notion that Pope Pius IX made a radical shift from beloved liberal to hardline reactionary after the revolution in Rome.

Instead, Hassard suggests a clear continuity between the pre-revolution Pius IX and the post revolutionary Pius IX …

Likewise, he undermines the idea that the Papal States were, as Wikipedia states, ‘already in rebellion against Papal rule’.

For whilst it is commonly claimed that the population of these states was rebelling and sought annexation, Hassard challenges this notion, noting that the deciding referendum:

Was duly carried out, under the protection of the Sardinian bayonets, with an apparatus of fraud, intimidation, and high-handed violence which seems incredible in a free country.

The voting-lists, prepared by the Sardinian agents, were restricted to the large towns, where the Mazzinians and the soldiers ensured a majority for the revolution; and so an apparent demand for annexation was carried by a vote of a fraction of one per cent, of the population [Italics mine].

So, so much more might be said. But we cannot write a book – only give, as we have said before, scant notes.

The reader needing clarifications must turn elsewhere. Again, either the online Catholic Encyclopaedia of 1917 or Wikipedia will furnish biographies of the important historical figures who appear in Hassard’s account.

These include Louis Napoleon Bonaparte III, Emperor of the French in the 1850s and 1860s – who should not be confused with his more (in)famous uncle.

There is also Victor Emmanuel who during this period becomes the King of Sardinia-Piedmont – and will later become the first King of a united Italy, after the Papal States and Rome have been conquered by Sardinia-Piedmont.

Let us also note the matter of the papal legations mentioned in the text, where we find Wikipedia‘s definition concise and helpful:

The term Papal Legation, in a territorial sense, refers to certain northern administrative regions of the erstwhile Papal States: specifically the “Legations” of Ferrara, Bologna, and Romagna.

These were then annexed to the Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont in 1860. Once again this is often called Piedmont in Hassard’s text to which we now turn – RB .

France Comes to the Rescue

WHEN the news of the flight to Gaeta reached Paris the government of Gen. Cavaignac was within ten days of its close, and the Roman question became a foremost issue in the approaching election.

Cavaignac immediately sent an envoy to Gaeta, and ordered a brigade of troops to be got ready ‘to intervene in the name of the French Republic for the restoration of the Pontiff’s personal liberty, in case he should have been deprived of it.’

In acknowledging this action the Holy Father expressed his gratitude for the attachment shown him by the French nation, and intimated a purpose of seeking hospitality at no distant day on French soil.

The correspondence was published by Cavaignac’s supporters as a bid for his re-election.

But Louis Napoleon [of France] bid a little higher. He was suddenly and opportunely afflicted by the conduct of his cousin, the Prince of Canino, with whom for a long while he had held no intercourse, and he wrote a note to the papal nuncio, lamenting that the eldest son of Lucien Bonaparte in

‘could not see that the temporal sovereignty of the venerable Head of the Church was intimately connected with the glory of Catholicism and the liberty and independence of Italy.’

The last line might be understood in different ways, but the note served its purpose. Louis Napoleon was elected President of the Republic by an immense majority.

There was no question that the restoration of the Pope would be speedily undertaken by foreign arms; for while the Catholic powers were determined to defend the rights of the Church, the czar and the king of Prussia were convinced that the overthrow of the Mazzinian Republic was necessary to the order of Europe.

It only remained to decide which should make the first move. Spain, during the month of December, addressed a note to France, Austria, Bavaria, Sardinia, Tuscany, and Naples, inviting them to consider the best means to reestablish the authority of the Pope, and hence originated a diplomatic conference at Gaeta, in which the proposed intervention was fully discussed.

It was France who took the lead, anticipating the action with which the other powers were quite ready to charge themselves.

Nothing could have been more complete than the justification of her course subsequently presented to the French Assembly by M. Thiers, in the form of an elaborate report from a committee. He considered the case in its political as well as its religious aspects:

In a political point of view an interposition was imperatively called for by the interests of Italy and Italian liberty; for the Pope would have been restored without us, and that by Austria. Austria, using the unquestionable rights of war, had reconquered Lombardy, invaded Piedmont, the duchies of Parma and Modena, Tuscany, and a part of the Roman States.

The governments, having met with an ill-return for the concessions they had made, were not disposed to renew them; the enemies of liberal reforms found a powerful argument in the excesses which had been committed; sensible persons were discouraged, and the masses, after so much dangerous excitement, were reduced to submission by the pressure of physical force.

Were no fragments of the hopes of 1847 to be saved? France did not think so, and such was the origin and the reason of her expedition to Rome. The question was whether France should suffer Austria to push her invasion as far as Rome, and thus to become both morally and materially the mistress of almost the whole of Italy.

The Catholic powers had assembled at Gaeta to plan the re-establishment of an authority, which is necessary to the Christian universe.

In truth, without the authority of the Sovereign Pontiff, Catholic unity would be dissolved; Catholicism would be severed into sects and perish; and the moral world, already so rudely shaken, would fall into universal ruin.

But Catholic unity, requiring a certain spiritual submission from Christian nations, would be inadmissible if the Pontiff, in whom it is embodied, were not perfectly independent; if, upon the territory which ages have assigned to him, and which all nations have respected, another sovereign, whether prince or people, were to rise to dictate laws to him.

For the Papacy there can be no other independence but sov ereignty. We have here an interest of a paramount na ture which is rightly made to overrule the private inter ests of nations, just as, in a state, the public interest overrules what is individual; and it fully justified the Catholic powers in re-establishing Pius IX upon the pontifical throne.

The conference at Gaeta met on the 3oth of March, and three weeks afterwards the French expedition embarked.

The troops, commanded by General Oudinot, landed at Civita Vecchia, and marched hastily upon Rome under the impression that there would be no serious defence.

The arm of Garibaldi and Avezzana was largely composed of Lombards, Genoese, and foreigners, and the Romans were supposed to be watching for the French as deliverers.

But General Oudinot underrated the revolutionary soldiers, and misunderstood the citizens.

The first attack was repulsed; it was only after a siege of two months, memorable for bravery on both sides, that the victorious army entered Rome, June 30, and Colonel Niel was despatched to Gaeta to present to the Holy Father the keys of his capital.

Austria had already restored the pontifical authority in the Legations. Mazzini, Garibaldi, and the other leaders of the ruined republic took flight.

‘Accept, General,’ wrote the Pope to General Oudinot:

My congratulations for the principal part which is due to you in this event congratula tions not for the blood which has been shed, for that my soul abhors, but for the triumph of order over anarchy, for liberty restored to honest and Christian persons, for whom it will not henceforth be a crime to enjoy the property which God has al lotted to them, and to worship in due religious pomp without danger to life or estate. With regard to the grave difficulties that may hereafter occur, I rely on the divine protection.

Pope Pius IX Refuses to Return to Rome

But the Holy Father did not at once resume his throne. Louis Napoleon’s complex policy in these events was not in accord either with the wishes of Catholic France or the sentiments even of the French Assembly, and he was false alike to the Pope and to his own people.

He was quite as anxious to further the ambition of Piedmont and encourage the aspirations of Young Italy as to thwart the influence of Austria by assuming the protection of the Holy See.

During the siege he sent M. de Lesseps to Rome to negotiate with Mazzini an accommodation which General Oudinot indignantly rejected.

Shortly, after the capture of the city Oudinot was replaced by General Rostolan.

The prince-president then wrote a letter to Colonel Edward Ney, in which, after declaring that

The French Republic had not sent an army to Rome to extinguish Italian liberty but to regulate it,’ he instructed this officer to inform the general that the French tricolor must not protect any act or policy inconsistent with the purposes of the intervention, and that the programme of the restoration ought to be u a general amnesty, lay administration, the Code Napoleon, and a liberal government.’

This was ostensibly a private letter, and the straightforward soldier, Rostolan, refused with warmth to permit its publication within his lines. It was accordingly printed at Florence, and Rostolan was speedily relieved; whereupon the French ambassador, M. de Courcelles, resigned.

No one understood better than Pius IX the ingrain duplicity of Louis Napoleon, and the complicity of this inveterate conspirator in the plots for the destruction of the temporal power.

He rightly interpreted the letter as an infringement of his independence and an attempt to bind the Holy See in servitude to the Bonaparte ambition; and he refused to re-enter his States until he could go in the fulness of his sovereign authority.

Cardinal Antonelli, henceforth until the day of his death the papal Secretary of State, commented upon the letter in a note to the governors of the pro vinces, remarking that it ‘had no official character,’ and was ‘viewed with displeasure even by the French authorities in Rome’ and adding:

‘The Holy Father is seriously occupying himself in giving to his subjects such reforms as he believes conducive to their true and solid good, nor has any power imposed laws upon him in reference to this.

It is the interest of all the powers to sustain the liberty and independence of the Supreme Pontiff for the peace of Europe.’

Meanwhile, the Pope appointed a commission of three cardinals to reorganise the government ad interim, and in September he removed to Portici, near Naples, whence he issued a motu proprio establishing boards for the reform of the laws and the finances, granting extensive provincial and municipal franchises, and admitting laymen to the administration.

An amnesty was declared for all except members of the successive revolutionary governments, chiefs of military bodies, those who had benefited by the previous amnesty and had broken their parole, and those who, besides political offences, had been guilty of ordinary crimes punishable by the existing laws.

For seven months, the Holy Father remained at Portici; and at last, having obtained from Louis Napoleon (whose schemes were not sustained by the French Assembly) the pledges which he demanded, he began his homeward journey.

Pope Pius IX Returns to Rome

His progress from town to town was a series of triumphs. Whatever disaffection there may have been in Rome and one or two other large cities and most of the contemporary accounts of these events are so colored by the political and religious prepossessions of the writers that they cannot be safely trusted.

There is no question that the rural population was devout and loyal, and welcomed his return with unfeigned joy.

In Rome, the clubs and secret societies did what they could to mar the celebration. Placards were posted in the Corso threatening death to all who should welcome ‘the priest Mastai.’

Twice during the night before his arrival the Quirinal was set on fire.

Nevertheless, when the cortege entered, on the 12th of April, 1850, the same gate of St. John by which the Supreme Pontiff had fled disguised and under cover of the night nearly seventeen months before, chc city seemed to be wild with delight.

‘The whole population of Rome,’ wrote the unsympathetic correspondent of the Journal ties Debats, ‘fell at the feet of their Pope and received his benediction. It was one of those grand popular commotions which can never be arranged to order, which spring only from deep popular feeling.’

The chapter of St. John Lateran met the procession as it entered the magnificent square in front of the venerable basilica the cathedral of the popes, the mother church of Christendom; the Pontiff descended from his carriage, and blessing the kneeling populace and soldiers, gave thanks to God before the grand altar of the church; he traversed the whole city, cheered at every step with enthusiastic vivas and entered St. Peter s, where the Te Deum was followed by the Benediction of the Blessed Sacrament.

Later in the day, the Holy Father received the diplomatic corps, the cardinals, the nobility, and others, at the Vatican, and in that famous palace, surrounded by priceless treasures of art and science, he now fixed his permanent residence, the Quirinal, with its melancholy associations, being henceforth hateful to him.

The demonstrations of rejoicing were prolonged for several days, with illuminations ot the whole city and services in the churches, and they culminated in the proclamation of a jubilee throughout the Christian world.

A Time of Peace

The task which now fell upon Pope Pius IX was hard and ungrateful. Despite the shouts which hailed his triumphant return, there was a bitter hatred of ecclesiastical government among the middle classes in Rome, a general corruption and demoralization of society, a decay of faith and devotional sentiment among the young.

The convulsions of the revolutionary period and the secret activity of the oath-bound associations had left effects which were not to be obliterated by a battle and a procession.

The restored government, owing its stability to a French anny of occupation, had to undertake the restoration of political and religious order under many trying and unnatural conditions.

The next few years are commonly described by unfriendly historians as years of severe reaction. This is a great mistake.

Certainly, the Pope made no more attempts to govern by the aid of a parliament, a radical ministry, and a democratic national guard; but he pursued the same general line of practical administrative reform which he had adopted in 1846.

He ruled with characteristic mildness.

He gradually relaxed the exceptions to the amnesty, so that a large proportion of the exiles were allowed to return.

He restored the shattered finances, redeeming even the worthless paper money issued by the insurgents.

He revived industry and trade.

He built up the declining population, so that Rome, which had 180,000 inhabitants at the time of his accession, and lost no fewer than 20, ooo during the reign of the revolution, contained 220,000 before the papal government was overthrown in 1870.

The French envoy, Count de Rayneval, sent an elaborate report to his Government in 1856 on the slate of society in the Papal States and the character of the Holy Father’s administration, which he declared to be one of the most equitable and benevolent in Europe:

‘Never,’ said he, ‘has a more exalted spirit of clemency been seen to preside over a restoration. No vengeance has been exercised on those who caused the overthrow of the pontifical government; no measures of rigour have been adopted against them.

The Pope has contented himself with depriving them of the power of doing harm by banishing them from the land.

No imprisonment, no trials even, have taken place, except occasionally in consequence of the obstinacy of certain individuals who, insisting on being tried, have been condemned, and punished by being presented with a pass port.

As to the flagrant conspiracies which followed the return of the Pope, it was his bounden duty to take measures against them as well as against the subsequent assassinations. These measures were taken in the most regular manner. The Holy Father never failed to mitigate the severity of the sentences.

Many of the persons most deeply compromised obtained their liberty after a certain time without the condition of exile.

At the present moment it is difficult to ascertain the exact number of exiles who are forbidden to enter the Roman States for political reasons; but with respect to the authors of the revolution of 1849, it is thought that it does not amount to a hundred.**

The count was at pains to dispel the common illusion that the papal rule was a government by priests. Outside of the capital the total number of ecclesiastics of all ranks employed in the administration was 98, against 5,059 laymen.

In Rome itself, where some of the departments, especially in the Ministry of Justice, were occupied partly with ecclesiastical affairs, the clerical officials were 96 and the laymen 5,000.

These figures did not include the Ministry of War, which had no ecclesiastical functionaries; on the other hand, the roll of the provincial employees of both classes was partly re peated in the statistics of the central ministerial bureaus to which they were subordinate.

The proportion of laymen to ecclesiastics in Rome and all the provinces was 80 to 1.

The criminal courts and inferior civil tribunals contained no ecclesiastics. With regard to the state of public feeling at that time, Count de Raynevai’s report was not reassuring.

‘In the lower depths of society,’ said he:

‘Carbonarism is kept up; it continues to make recruits; the dagger here is still held in honor; the end to be obtained is the upsetting of every social hierarchy.

The followers of Mazzini form already a class in some degree above these. The universal republic, the unity of Italy, constitutional govern ment, war against Austria, is their programme.

Directed by the committees of London and Geneva, their watchword for the present is quiet and in action until the return of their chiefs by means of an amnesty and the departure of the foreign troops, give them an opportunity of operating with a chance of success.

This section extends to a certain portion of the middle class. This class, and the higher classes in general, are tormented with the desire of taking a part in public affairs.

The example of Piedmont is turning their heads.

Convinced that the presence of the Pope is an invincil to the realization of their projects, they earnestly pray for the annihilation of the pontifical power.

Taxed more lightly than the majority of European countries, they complain that they are crushed under the weight of fiscal imposition.

At the same time they complain of the state for not undertaking great, works which it is their duty to undertake themselves.

Finally, they profess to have a great fear of the Mazzinians, and at the same time are opening the door to them.

Between the party of progress and the extreme conservatives was a large body of orderly citizens, indifferent to everything except their own prosperity.

Anywhere else such a party would furnish the government with a good point d’appui; but where the only universal rule is Laissé Faire with the reservation of the right of complaining when the thing is done instead of be forehand, how can such friends be trusted ?

Such was the condition of Rome when the Holy Father returned from exile.

But for a few years an outward peace was preserved, and under the influence of institutions of religion and education and the advance in material prosperity society began to recover a more healthy tone.

The interests of the universal Church received the most watchful care during this anxious time. In Austria, in some of the smaller German States, in Tuscany, in Naples, in Portugal, in South America, Pius obtained, by concordats or otherwise, the abrogation of laws that obstructed the independence of the Church.

In September, 1850, he restored the Catholic hierarchy of England, appointing Dr. Wiseman Archbishop of Westminster, with twelve suffragan sees an act which provoked an extraordinary outbreak of English bigotry, but gave a great impulse to the progress of the faith. The episcopate was also restored to Holland. The Eastern Church was exhorted to return to Catholic unity; and the Catholics of Armenia were addressed by an encyclical letter.

The Church in the United States was strengthened by the creation of the archbishoprics of New York, Cincinnati, St. Louis, and New Orleans (1850); and in 1853 Monsignor Bedini, nuncio to Brazil, was sent to this country as a special envoy, bearing an autograph letter of salutation from Pius IX to President Pierce a mission which the United States representative at Rome, Mr. Cass, in his official despatch to the Secretary of State, described as ‘a new and additional testimonial of the highly favorable and friendly sentiments entertained by His Holiness Pius IX towards the government and institutions of the United States.’

The disgraceful scenes of mob violence which disturbed the journey of this amiable and distinguished prelate, and the still more disgraceful failure of the public authorities to protect him, will long be remembered with shame by American citi zens.

The Dogma of the Immaculate Conception

But the most important event of the short days of peace was the formal definition of the doctrine of the Immaculate Conception of the Blessed Virgin Mary as an article of the Catholic faith.

The letter to the bishops of the world, written during the banishment at Gaeta, had been answered by a multitude of addresses from all parts of Christendom, testifying the faith and desires of the people.

The commission of cardinals had collected the concurrent teachings of the past ages. In July, 1854, a jubilee was proclaimed in preparation for the solemnity, and the 8th of December, Feast of the Immaculate Conception, was appointed for the definition.

Forty-three archbishops and ninety- two bishops gathered at Rome, with the full college of cardinals, for this memorable occasion.

The bull was considered in a general meeting of the fathers; but when the question arose whether the dogma should be penned in the name of the assembled episcopate or by the sole authority of the Sovereign Pontiff, a scene occurred, which is thus described by Monsignor Audisio, who was an eye-witness of it:

It was the last session; noon had just struck; the bishops knelt to recite the Angelus. After they resumed their places a few words only were spoken, when suddenly an accla mation to the Holy Father broke out, a cry of eternal adhesion to the primacy of the see of St. Peter: Petre, doce nos; confirma fratres tuos! (Peter, teach us; confirm thy brethren!) and the debate closed.’

Thus the nature of the definition, as the exercise of the Pontiff’s supreme and infallible magisterium, was clearly demonstrated.

The gathering of the bishops was in no sense an ecumenical council, and the doctrine of the papal infallibility was distinctly asserted, with the joyful assent of the whole Catholic world.

Here, then, we have the first of that series of striking manifestations of the plenitude of the teaching authority of the Pope personally which have already been referred to as a marked characteristic of the pontificate of Pius IX

On the morning of the 8th of December the bishops in white copes and mitres assembled around the Pontiff in the Sistine Chapel, and, chanting the Litany of the Saints, proceeded in order of rank down the grand staircase of the Vatican and into St. Peter’s.

All knelt for a moment before the chapel of the Blessed Sacrament, and then the procession moved on to the grand altar beneath the dome, where Mass was celebrated in presence of His Holiness.

It was after the Gospel had been chanted, in Latin and Greek, that the dean of the Sacred College, accompanied by the senior archbishop and senior bishop present, and archbishops of the Greek and Armenian rites, advanced to the throne and besought the Vicar of Christ to pronounce the definition.

It is related that when the Holy Father, after the singing of the Veni Creator, rose in the midst of the vast and silent multitude and read the decree, his voice trembled and broke, and his eyes filled with tears.

To commemorate the solemnity he afterwards caused a column of white marble, surmounted by a bronze statue of the Virgin Immaculate, and encompassed at the base by figures of Moses, David, Isaias, and Ezechiel, to be erected opposite the Propaganda.

Innovations, Achievements and Beneficence of Pius IX

The condemnation of errors in faith and philosophy into which distinguished Catholics like Gioberti and Ventura had been betrayed; protests against the violation of the rights of the Church and the freedom of conscience by secular governments; the completion and consecration of the splendid basilica of St. Paul-without-the-Walls, destroyed by fire in the days of Pius VII, and rebuilt by the care of successive popes; the restoration of the ancient church of St. Agnes in Via Nomentana, in remembrance of a providential escape from death at the convent of St. Agnes, in April, 1355, when the Pope and a large number of other persons were precipitated fifteen or twenty feet, amid rubbish and broken tiles, by the giving way of a floor – such were some of the labors which filled the ten years following the restoration.

Education was promoted by the enlargement of the faculties of the universities, the opening of schools, and the establishment of new colleges.

The Seminario Pio was founded at the Pontiff’s private cost to train a chosen body of priests selected for merit from the various dioceses of Italy. The Collegio Pio (a different institution) was designed for English ecclesiastics, and especially for converts from Anglicanism.

Theological schools were created and endowed for the French, for the Spanish-Americans, and later for the United States, the building which the last-named establishment occupies being the Holy Father’s gift.

Charitable and industrial enterprises were multiplied. The construction of railways and telegraphs was fostered.

The fine arts found in Pius IX a generous patron, the museums a munificent benefactor; his enthusiasm inspired the antiquary; his purse defrayed the cost of excavations; his enlightened care preserved monuments of Christian and pagan antiquity, and rescued early paintings and mosaics from impending ruin.

He built one of the great buttresses; which saved the crumbling walls of the Colosseum, and restored some of the masonry to its original condition. He turned aside the flow of water which threatened the triumphal arches of Constan- tine and Septimius Severus.

He completed costly explorations in the Roman Forum, and caused the recovered fragments of architecture to be placed and secured in their proper position.

He uncovered the long-hidden Appian Way. He pursued with rich results the long-pending excavations of the Palace of the Caesars.

He established the Commission of Sacred Archaeology, under which such magnificent work has been accomplished in the Catacombs; and he founded the Christian Museum at the Lateran, for the reception and dis play of the priceless relics of Christian antiquity.

Many of the works I have thus hastily enumerated were still in progress at the close of his government; many were prosecuted at his expense up to the close of his life, although the kingdom of Italy had appropriated to itself the objects upon which so much care was expended.

In May, 1857, the Pope began a tour through his States, passing by Spoleto, Loreto, Sinigaglia, and Imola to Bologna, and returning by Pisa and Volterra.

At various cities on the route, he received distinguished guests the Austrian Archduke Maximilian, the Governor of Lombardy and Venice, the Duke and Duchess of Modena, the Duchess of Parma, the King of Bavaria and at the request of the Grand Duke of Tuscany he visited Florence, where magnificent quarters were prepared for him in the Pitti Palace.

He spent four months on the journey, inspecting a vast number of public institutions, and giving especial attention to the reform of the prisons, which was always an object very dear to his heart.

Everywhere the people received him with the warmest marks of affection, and the legations, which had been in rebellion against his authority so short a time before, and were to be separated from his dominions so short a time afterward, were prodigal in demonstrations of loyalty.

In like manner, his return to Rome was made a popular festival. Those who know the unstable and excitable disposition of the Italian people will not find it hard to believe that their acclamations were sincere and their enthusiasm was genuine though fleeting.

Some Personal Encounters with Pope Pius IX

In this stately progress Pius IX was no less accessible to the poor than during his walks at Rome.

A sick woman threw herself in the way as he passed and cried: ‘Holy Father, I am a poor dying mother, and these two children that you see will be left destitute if I am taken. Save me! Give me back my life!’

‘My poor child,’ said he, ‘I am not what you take me for. I have no power over your disease, but I have a heart to feel for you and a word of hope to console you. God is infinitely good. Perhaps you do not pray enough. Come, now; for nine days address yourself to him who is the Providence of orphans and of mothers. I will unite my prayers with yours during the same time, and I hope Heaven will hear you. Let us begin at once.’

The Pope and the poor woman knelt down together, and all the Holy Father s suite likewise fell on their knees. What became of the woman afterwards we are not told.

A family from New Orleans visiting Rome had with them a slave named Margaret, who, being a devout Catholic, was very anxious to stand where she could see the Pope and get his blessing.

Pius heard of the woman, and the next day a papal dragoon was seen riding up and down the Via Condotti, making enquiries for ‘Mademoiselle Marguerite,’ for whom he had a letter of audience.

At the appointed time the poor slave found herself waiting in the midst of a brilliant company at the Vatican. When the Pontiff was disengaged the first name called was that of ‘Mademoiselle Marguerite.’

‘My child,’ said the Holy Father, ‘there are many great people waiting, but I wish to speak to you the first. Though you are the least upon earth, you may be the greatest in the sight of God.’

He talked with her for twenty minutes, enquired about her condition and her fellow-slaves, and dismissed her with a blessing for herself and ‘all those about her.’

The welfare of the negroes in the Southern States of America always gave him deep concern, and special missions among them were organized with his assistance and his particular benediction.

His tender heart warmed instinc tively to all who were in bondage or in prison. Giving audience to an English bishop who was about to sail for his diocese at Hobart Town, he said: ‘Be kind, my son, to all your flock, but be kindest to the condemned.’

When Jefferson Davis was imprisoned at Fortress Monroe Pius sent his likeness to the ex-President of the Confederacy, writing underneath: Venite ad me omnes qui laboratis et et onerati estis et ego reficiam vos, dicit Dominus (‘Come to me all you that labor, and are burdened ; and I will refresh you, saith the Lord’).

When the cholera was raging in Rome he went to the hospitals, not to pay a formal visit, but to minister to the sick with his own hands and assist them in their last agony.

In the cholera hospital for women a poor Jewess died in his arms. The sick soldiers in the military hospitals were the objects of his most affectionate care.

One day, when all the attendants, as well as those patients who were well enough to be out of bed, were kneeling for his blessing, he saw a young man in the background, standing, but with an air of respect and embarrassment.

‘Why do you not come to me like the others?’ said Pius.

‘Holy Father, I am a Protestant physician.’

‘ A physician! Well, what of that? I like physicians; I owe them a great deal. But you say that you are a Protestant, too. Ah, my son, what do you protest against, and why do you pro test?’

And so saying he blessed the young man and went on without waiting for an answer. But his questions were like the seed that bore good fruit, and in a few days the doctor was received into the Church.

The Mortara Case

It was just after the Pope’s return from the tour of his States that the notorious ‘Mortara case ‘ threw the Protestant world into a paroxysm of anti-popery excitement.

The Church, regarding the true faith as the most precious of gifts, held that a child baptised into the fold of Christ must not be deprived of the privilege this sacrament confers, even by the authority of its parents. Hence, by an old law of the Roman States, it was provided that the baptized children of Jews should be removed from the parental control and brought up as Christians.

To protect the rights of the family, however, it was forbidden to baptize the child of a Jew without the consent of its natural guardians, unless the child were at the point of death; and, as a further precaution, Jewish households were prohibited from hiring Christian servants.

In contravention of this law an Israelite family of Bologna,named Mortara, employed a Christian servant, who baptized the boy Edgar while he was dangerously ill, and on his recovery he was removed, in his seventh year, to the House of Catechumens at Rome.

Denunciations of this transaction came with a bad grace from the Liberals of Europe, who were asserting the right of the state to control the religious belief of its subjects; with a still worse grace from the Protestants of the United States … where little vagrants, imprisoned in Houses of Refuge, are not allowed to practise the religion of their parents or receive the ministrations of a priest being condemned to Protestantism for life as a punishment for poverty and idleness.

‘You are very dear to me, my son,’ said Pius to young Mortara ten years afterwards,

For I bought you for Christ with a great price. Yes, you cost me a large ransom. On your account a storm of invective broke out everywhere against me and against the Apostolic See. Governments and peoples, the powers of the earth, and journalists, who are also mighty ones in these days, declared war against me.

Sovereigns even took the field and sent me diplomatic notes through their ambassadors, all on your account. They complained of the wrong done to your parents because you were regenerated by holy baptism and received such instruction as it pleased God that you should have; but nobody pities me, the father of all the faithful, when schism tears from me thousands of children in Poland or corrupts them by pernicious teachings.

The peoples arid the governments have nothing to say now when I cry out against the cruel wrong done to this part of the flock of Christ, ravaged by the robber in full day. Nobody stirs to help the father and his children.’

Victor Emmanuel and the Anti-Christian Conspiracy of Revolution

Driven out of Rome by the victory of the French arms, the atheistic conspiracy transferred itself to Turin.

The peoples, as the event proved, were not yet ready for the war which Mazzini proclaimed in their name, and once more the revolution trusted its faith to princes.

Its objects were unchanged; its animosity against the Catholic faith as the bulwark of political order, and the Holy See as the centre of Christian society, was unmitigated; but its methods of attack were accommodated to new circumstances.

To destroy Catholic unity by detaching national churches from their supreme bishop, to silence the clergy, to disperse the religious orders, to expel God from the schools this was the system of education which Mazzini laid down for his followers, and this was the scheme which they applied to their operations in Italy.

Crushed by the disaster of Novara in March, 1849, the unfortunate Charles Albert abdicated in favor of his son, Victor Emmanuel, and after visiting, alone and unknown, a mountain convent where he confessed and received the Blessed Eucharist he retired to Portugal, and there he soon died.

Victor Emmanuel was more easily controlled by the secret societies than his chivalrous father, ard what manner of bargain he made with them for the crown of Italy we may judge from the facts of history.

The secularization of teaching began in Sardinia during the last years of Charles Albert; the active persecution and spoliation of the Church followed almost immediately upon the accession of Victor Emmanuel.

Persecution of the Church Begins in Italy

For instructing his clergy how to conduct themselves with reference to a law in fringing on ecclesiastical rights the Archbishop of Turin was marched to jail under a guard of soldiers.

A second time he was arrested and im prisoned, forbidden to communicate with his vicar-general, and at last banished. A prison chaplain who asked prayers for him was dismissed from his employment. The Archbishop of Cagliari was likewise banished, and the property of both the illustrious exiles was confiscated.

The Archbishop of Sassari was placed under arrest. In less than ten years fifteen out of the forty-one sees in the kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont were empty, either by the expulsion of the bishops or the refusal of the Government to allow vacancies to be filled.

Police agents were instructed to watch for the publication of pastorals or the uttering of ‘observations savoring of insubordination’ from the pulpit and to arrest the authors of such discourses without delay.

Heavy taxes were laid upon church property, priests were reduced to beggary, and finally, in 1855, a general law was adopted, in direct violation of the constitution of the kingdom, suppressing religious communities and corporations and confiscating all their property.

By this act nearly eight thousand members of pious communities were deprived of their homes and possessions.

But even before the passing of the law many of the convents had been summarily emptied, and nuns had been turned into the street at night and without warning.

A series of attacks upon Christian education culminated with the establishment of a state school of heretical theology.

In the university of Turin it was taught that the state is omnipotent over the Church, that matrimony cannot be proved a sacrament, that the Church has no right to pronounce upon the impediments to marriage, and that the temporal power of the Pope is incompatible with his spiritual power.

The Holy See condemned these teachings, but the Government ordered that all professors in the diocesan seminaries should follow the same programme; and, finally, that no clergyman should receive a benefice without having attended the proscribed school.

The Holy Father protested against all these wrongs in diplomatic notes, in allocutions, in eloquent letters to the imprisoned con fessors; but the government replied with insults.

Count Cavour Proposes Seizing the Papal States

Then came the demonstration of Count Cavour at the congress of 1856, when, with sublime effrontery, considering what he was doing, he declared the Papacy:

A source of perturbation to the tranquillity of Europe and a focus of disorder in the centre of Italy.

He proposed the separation of the Papal legations from the rest of the Roman States and their government, ‘for a time,’ by a pontfical lay vicar.

It is well understood that the unexpected introduction of the Roman question at this congress was in pursuance of a private arrange ment between Victor Emanuel and Louis Napoleon; and indeed, when Count de Rayneval, in the document from which I have already quoted, answered the charges against the papal administration, his report was suppressed in France, and only saw the light through the enterprise of a daily journal in London.

The congress refused to consider the scheme advanced by Count Cavour; the Prussian plenipotentiary complained that the tendency of the discussion was to provoke in Italy ‘a spirit of opposition and revolutionary agitation’; and Count Buol afterwards wrote to Cavour :

The enemies of society will not cease their warfare against the legitimate governments of Italy so long as they find powers which back and protect them, and statesmen who appeal to those passions and those efforts which aim at the overthrow of all authority.’

But the mere introduction of the Sardinian protocol served the desired purpose.

‘It is the first spark,’ said Count Cavour’s own newspaper, ‘ of an irresistible conflagration.’

‘It has given a vigorous impulse to agitation,’ said another Liberal journal, ‘and now we have only to take care that it does not flag, and to keep it up till the decisive day arrives.’

The speeches of ministers in the Sardinian parliament certainly helped wonderfully to ‘keep it up,’ and to strengthen the conviction that whenever the insurgents chose to act they would be supported by the Piedmontese troops.

‘It will be remembered,’ said the Mazzinian organ E Italia e Popolo:

That after the memorable parliamentary discussion the Sardinian Government, in order to rekindle the fire which slumbered in the other provinces of Italy, had the speeches of Cavour and Buffa printed and disseminated in thousands throughout the duchies, the Romagna, Lombardy, Naples, and Sicily.

Nay, it excited by its emissaries the inhabitants of these States; and the words ‘Long live Victor Emmanuel!’ were written on the walls and doors of houses at Carrara by Piedmontese agents.

Still more flattering and more explicit assurances were given to the partisans of Piedmontese rule who came to Turin.’

And yet, according to Count Cavour, it was the Papacy which disturbed the tranquillity of Europe and fomented disorder in the centre of Italy!

Well did Louis Napoleon, in his message to the French Assembly in 1849, declare that:

The attacks upon the Pope were not the movement of a people but the work of a conspiracy.

On the 14th of January, 1858, Orsini made his attempt upon Napoleon’s life, and from his prison he warned the emperor that the Carbonari held him to his ancient engagements:

So long as Italy shall not be independent the tranquillity of Europe and that of your majesty will be but a chimera.

From this time there was no more mystery about Napoleon’s purposes.

He had a long private conference with Cavour at Plombieres, and on the ist of January, 1859, he made the famous unfriendly remark to the Austrian ambassador at the Tuileries which proved the signal for the Franco-Italian war.

A month later appeared his pamphlet, Napoleon III and Italy, in which he denounced the civil government of the Pope as incompatible with modern civilization, and proposed anew the double-headed confederation of Gioberti, with the King of Sardinia-Piedmont as military chief and the Sovereign Pontiff as honorary president.

It was one of the counts in this indictment of the Holy See that the Pope was obliged to enforce his authority by the aid of foreign soldiers.

Pius IX replied by a note addressed on the 27th of February to France and Austria, thanking them for their good offices, but requesting them to withdraw their troops from the Pontifical States, as the papal government was now able to preserve order.

This, however, did not suit the purposes of the French and Sardinian conspiracy. The troops remained.

Piedmont-Sardinia Plots to Usurp Florence, Parma and the Papal States

Piedmont, in the meantime, prepared the revolt in all the Italian States.

‘It is my belief,’ wrote the British representative at Florence to his Government,

that the insurrection at Parma was only part and parcel of an elaborate Piedmontese conspiracy, aided by the republican party, and having its ramifications throughout every town in Italy.

Garibaldi, now a general in the Sardinian-Piedmontese service, issued a circular instructing the conspirators how to act:

1. As soon as hostilities have commenced between Piedmont and Austria you are to rise with the cry of Italy for ever! Victor Emmanuel for ever!

2. Wherever the insurrection triumphs, he among you who enjoys most public esteem and confidence is to take the military and civil command, with the title of provisional com missioner, acting for King Victor Emanuel, and to retain it until the arrival of a commissioner sent by the Sardinian Government.

But it is unnecessary to quote proofs of the plot.

Mazzini himself laid it bare when he attacked the Government on account of its prosecution of the authors of the abortive revolt at Genoa, in 1857:

Monarchico-Piedmontese committees exist at Rome, Bologna, Florence, and several cities of the Lombardo- Venetian kingdom, and there are secondary centres in several other towns. I could name to you the persons, several of them deputies, who are the agents between the poor dupes and the personages of the Government.

In Florence, the plot against the Grand Duke of Tuscany, which resulted in his abdication after his troops had been bribed to desert him, was matured in the very house of the Sardinian ambassador.

In Parma, the Sardinian agents instigated the expulsion of the Duchess Regent, who was yet so popular that her subjects spontane ously recalled her, and Victor Emanuel had to drive her out a second time.

In the papal provinces, the action of Sardinia was stiil bolder, and as fast as the revolutionary disturbances broke out the Piedmontese commissioners took possession without ceremony.

The Marquis Pepoli, who was a leader in these transactions, and afterwards one of Victor Emanuel’s ministers, stated in the Chamber of Deputies at Turin that the outbreak never could have been provoked at Bologna if the king had not furnished the money for it from his private purse.

Before the peace of Villafranca, a large part of Central Italy was in the hands of the Piedmontese commissioners. By the terms of that treaty the commissioners were to be withdrawn; and the letter of the agreement was, indeed, complied with.

The Annexation of the Papal States Begins

Yet hardly were the signatures to the convention dry when Victor Emmanuel was found to be setting up a military provisional government over the duchies and the legations, and preparing for a fictitious plebiscitum on the question of annexation to Piedmont.

The affairs of Italy were to have been submitted to a European congress, invited to meet at Paris early in 1860, but on the 22d of December appeared a second pamphlet from the Tuileries which made the assembling of a congress impossible.

In this manifesto, entitled The Pope and the Congress, it was urged that the Holy Father should surrender the provinces of the Romagna, and content himself with the guarantee of the smallest territory consistent with his independence.

The publication was anonymous, but nobody doubted that it expressed the emperor’s sentiments, if it was not actually the work of his hand.

A week later the Official journal of Rome contained a note denouncing it as a veritable homage to revolution:

and a subject of grief to all good Catholics. Its arguments are only a repetition of errors and outrages many a time directed against the Holy See and many a time victoriously re pelled.

If the purpose of the author is to intimidate the Holy See, which he threatens with such terrible disasters, let him remember that he who has right on his side, who rests his cause on the solid and immovable foundations of justice, and above all is sustained by the protection of the King of kings, has certainly nothing to fear from the snares of men.’

On the 1st of January, 1860, in receiving Gen. Oudinot, the commander of the French troops at Rome, Pius referred again to this pamphlet as ‘ a monument of hypocrisy and an ignoble tissue of contradictions.’.

‘We hope,’ said he:

That with the help of the divine light his majesty will condemn the principles set forth in this work, and we are the more convinced that he will do so because we possess several documents which his majesty had the goodness to place in our hands some time ago, and which are a direct con tradiction of the principles in question.’

Monuments of hypocrisy were, indeed, all the letters addressed at this time to the Holy See by the courts of the Tuileries and Turin, both protesting the most ardent desire to defend the independence which they had been for ten years attacking, and the most filial devotion to the interests of the Church which they robbed and oppressed.

Pius IX replied to them all with dignity and firmness, knowing well the afflictions that were in store for him, never temporizing, standing brave and majestic as the one champion of truth and justice in the midst of an unfaithful world.

‘Whatever may happen, I must declare openly,’ he wrote to Napoleon:

that I cannot surrender the legations without violating the solemn oaths which bind me, without producing disorders in the other provinces, without committing a wrong and giving scandal to all Catholics, without impairing the rights not only of the sovereigns of Italy who are unjustly deprived of their domains, but also of the sovereigns of the entire Christian world, who cannot look with indifference upon the overthrow of principles.

Your majesty believes that the repose of Europe depends upon the cession by the Pope of the legations (which for the past fifty years have been the occasion of so much embarrassment to the Pontifical Government).

But, as I promised at the beginning of this letter to speak with entire frankness, let me return to this argument.

Who can count the revolutions which have happened in France in the past seventy years?

But who would dare say to the great French nation that, to secure the repose of Europe, it must restrict the limits of the empire?

The argument proves too much; you must allow me to reject it.

Besides, your majesty is not ignorant by what agents, by whose money, and by what support the risings at Bologna, Ravenna, and other cities were arranged. . . .

We must both appear before the Supreme Tribunal to give a strict account of our thoughts, words, and deeds.

Let us try so to appear at the judgment-seat of God that we may feel his mercy rather than his justice. I address you thus as a father who has the right to speak the naked truth to his children, however high their position in the world.

To Victor Emmanuel, whose insincerity was so flagrant as to be insulting, the language of the Holy Father was at once more severe and more tender:

Your majesty may read my answer in the ency clical letter which is about to appear. Let me add that I profoundly grieve not for myself but for the unhappy state of your majesty s soul, burdened as you are with so many censures, which, alas! will be increased when you and yours shall have consummated the act of sacrilege which you are about to commit.

May the Lord deign to enlighten you and yours, and give you the grace to see and deplore the scandals and the frightful evils which have afflicted poor Italy with your co-operation!’

The plebiscitum, nevertheless, was duly carried out, un der the protection of the Sardinian bayonets, with an apparatus of fraud, intimidation, and high-handed violence which seems incredible in a free country.

The voting-lists, prepared by the Sardinian agents, were restricted to the large towns, where the Mazzinians and the soldiers ensured a majority for the revolution; and so an apparent demand for annexation was carried by a vote of a fraction of one per cent, of the population.

CSJ.org Note: If only the above statement that voting was restricted to large towns and that the vote was carried by less than 51%, it is sufficient, in itself, to demonstrate that the population of the Papal States clearly wished to remain with the Pope.

For there is a clear and obvious reason that only large towns would be counted: it was only in urban centres there was any hope at all of a majority …

During these revolutionary times across Europe in Italy as well as France, Spain etc the rural population and those in smaller towns were markedly traditional and conservative.

It is also exceedingly unlikely that women were allowed the vote and in the traditional Catholic society of that time women were noticeably more devout, more pro-Catholic and more anti-revolution.

All of this, of course, is to say nothing of Hassard’s claims of intimidation and fraud – RB

On the 18th of March, 1860, the six Papal legations, Bologna, Ferrara, Forli, Ravenna, Urbino e Pesaro, and Velletri, together with the duchies of Parma, Modena, and Tuscany, were declared annexed to the Sardinian monarchy.

The king communicated the news to the Pope in a letter full of expressions of respect for religion and unalterable devotion to the Catholic faith. The Holy Father replied:

I might say that the pretended vote was forced and not voluntary; I refrain from asking your majesty’s opinion of this sort of universal suffrage, as 1 also refrain from expressing my own. I might bring forward many other considerations.

But what above all compels me to dissent from your majesty s views is the spectacle of the steady in crease of immorality in these provinces, and the insults which are there heaped upon religion and its ministers.

Moreover, I am not only unable to regard your majesty s schemes with any favour, but I protest against the acts of usurpation committed up on the States of the Church, which leave upon the conscience of your majesty and all other co-opera tors in this unworthy spoliation the fatal consequences that must flow from it.

I am persuaded that when your majesty reads again, with a calmer and less prejudiced mind and a better knowledge of the facts, the letter which you have addressed to me, you will find in it many reasons for repentance.

I pray God to give your majesty the graces of which you have special need in the difficult circumstances of the moment.

But Pius IX was not content with these noble personal remonstrances.

On the 26th of March he issued a bull of excommunication against all who took part in the ‘rebellion, usurpation, occupation, and criminal invasion ‘ of the States of the Church.

The French Government, which had suppressed L’ Univers for printing the papal encyclical of January 19, forbade the publication of this bull in France.

It gave full license to the Liberal and official journals to publish a forged bull, and to ridicule and denounce its extravagant language; but when the bishops tried to expose the forgery the press was closed to them.

Formation of the Papal Zouaves

Deserted or oppressed by all the governments of the world, and foreseeing the stormy days that were soon to come, Pius IX preserved the calmness and resolution that always adorned his saintly life and that appeared more beautiful than ever in the darkest days of trouble …

‘If the cabinets have their policy,’ said he one day to a visitor who was speaking of the difficulties of the situation, ‘so have I mine.’

‘Will your Holiness explain it to me ?’

‘Willingly, my son: Our Father who art in heaven, thy kingdom come, thy will be done. That is my policy; I have no other. Be sure it will triumph.’

Having lost his revenues by the seizure of the legations, he invited the faithful throughout the world to contribute to the support of his government as well as of the administration of the affairs of the universal Church.

At once began the extraordinary collections of ‘Peter’s pence ‘which for the past eighteen years have so signally illustrated the devotion of the Catholic populations to the Holy See.

France had given notice that it would soon be necessary to withdraw the army of occupation indeed, even without such notice the Sovereign Pontiff knew that he could never depend upon Louis Napoleon to protect him against revolutionists or Sardinians and the formation of a defensive force of 20,000 or 25,000 volunteers was begun under the gallant French General La Moriciere, a hero of the Algerian wars, who had always refused to serve under the Second Empire.

Monsignor de Merode, a Belgian, formerly a soldier, and, like La Moriciere, a veteran of Algeria, became Minister of War. There was a perfect understand ing between the Holy Father and these two flaming and untiring spirits.

‘ See,’ said Pius, ‘ I am well served! I have for ministers a thunderbolt and a hurricane.’

The volunteers were mostly young and ardent Catholics, from France, Spain, Ireland, Belgium, Holland some even from America who felt, as their general did, that the cause of the Pope, desperate as it looked to the world, was one for which a man might be happy to die.

Many of them gave their money as well as their persons.

CSJ.org Note: Let us note this is clearly true and that Charles A. Coulombe has written a remarkable book on the Papal Zouaves that contains moving firsthand reports to this effect from letters from the volunteers.

There is a review of this book on the Papal Zouaves here at this site – and that review may also further serve to clarify the issues here – RB.

‘The revolution menaces Europe today,’ said La Moriciere in taking command of this army, ‘ as Islamism menaced it of old; and today, as of old, the cause of the Papacy is the cause of civilization and liberty.’

Annexation of Umbria and the Marches

But Sardinia-Piedmont, having an agreement with Napoleon, was not seriously obstructed by this brave little force in her advance towards Rome.

The next step was the occupation of Umbria and ihe Marches, and this was even a simpler operation than the seizure of the Papal legations.

The expedition was concerted at Chambery between the French emperor and the Piedmontese General Cialdi, and in closing the interview the emperor is reported to have said, Faites, mais faites vite! – almost the very words which our Lord spoke to Judas at the Last Supper: ‘ That which thou dost, do quickly ‘

Seventy thousand Sardinians immediately marched to the papal frontier, and Gen. Fanti sent word to La Moriciere, who was disposing his volunteers to meet the operations of Garibaldi on the pontifical territory, that ‘if the papal troops used force to suppress any rising whatever in the Roman States, he would immediately occupy Umbria and the Marches.’

La Moriciere was himself too frank and chivalric to realize the mendacity of Napoleon, and when the French ambassador solemnly assurec Cardinal Antonelli that the Piedmontese troops would be compelled to respect the boundary line, and confine themselves to the suppression of the Garibaldians, he believed these representations, in spite of what was passing before his eyes.

A despatch from M. de Gramont, the ambassador at Rome, confirmed him in this error. ‘ The emperor has written from Marseilles to the King of Sar dinia,’ said this telegram, ‘ that if the Piedmontese troops enter the pontifical territory, he will feel it his duty to oppose them.

Reinforcements will arrive at once from Toulon. The government of the emperor will not tolerate the culpable aggression of the Sardinian Government.’

The despatch was submitted to Cialdini, who had al ready begun the inarch of invasion. He put it in his pocket, saying : ‘I knew about it before you; 1 have been with the emperor.’ The messenger asked for a receipt.

‘ There,’ said Cialdini, contemptuously signing one, ‘that will do to go with the other diplomatic papers.’

With 5,600 volunteers La Moriciere and Pimodan heroically confronted the 45,000 troops of Cialdini at Castelfidardo, September 18, 1860, the Papal Zouaves beginning the day of battle by receiving the Holy Eucharist at dawn. They were defeated with serious loss.

The brave Marquis de Pimodan fell during the engagement. La Moriciere, with a remnant of his force, made his way to Ancona, and, still hoping for the intervention of one or more of the Catholic powers, prolonged the defence of that city against a combined land and naval attack until the 29th.

His capitulation at last, when resistance was no longer possible, left the Pope without an army, and the Sardinians masters of everything except the city of Rome and the small territory close around its walls. Garibaldi, in the meantime, with the secret assistance of the Sardinian Government, and in the face of a farcical op position from the Sardinian fleet, which carefully failed in its pretended attempts to intercept him, had roused the island of Sicily.

Victor Emmanuel speedily took possession of the whole territory of Naples, and in March, 1861, assumed the title of king of Italy.

The dethroned king of Naples, son of the monarch who had so generously entertained Pius at Gaeta, fled to Rome, and there found a princely reception.

Victor Emmanuel complained; Napoleon half threatened to withdraw his troops if the exile were not expelled.

But the Pope, reminding the French emperor of the refuge which Pius VII. had held open to the family of Napoleon I., remarked that it was a tradition with the Roman Pontiffs to show hospitality to their persecutors, and much more to their benefactors.

The policy of the emperor became more and more open in its hostility to Rome. He forbade the Catholics of France to subscribe for a sword of honor for La Moriciere; he deprived the French volunteers of their citizenship as a punishment for serving the Pope. He summoned home Gen. Goyon, the commander of the French troops at Rome, because he was too stanch a friend of the Sovereign Pontiff. The general did not understand the motive of these orders. ‘ I am called to France, Holy Father,’ said he, in taking leave; ‘not /rcalled.’

‘Go, my son,’ was the reply; ‘you will find there at Paris.’

The Pope was right. In September, 1864, Napoleon signed a convention with Victor Emmanuel, by which it was agreed that the French army should evacuate Rome within two years, and that the Pope should be secured in the possession of the territory which he then occupied, the Government at Turin binding itself neither to invade that little State nor to allow it to be invaded by others.

The Italian capital was to be removed from Turin to Florence.

But the Piedmontese Government never had an idea of keeping long to the terms of the convention, and the very statesmen who put their names to it de clared that it would in no wise hinder their designs upon Rome.

The Pope was not consulted in this arrangement of his future and parcelling out of his property. When he heard of it he said: ‘I pity France.’

Doubtless, he saw the true meaning of the convention, just as did the Marquis Pepoli, who was one of Victor Emanuers plenipotentiaries in the negotiation. ‘

It breaks the last link,’ said the marquis, ‘which connects France with our enemies – the enemies being the Holy See and the Catholic religion.’

* Another authority, of the same date, shows that the whole number of clerical functionaries in Rome and the provinces (not including prison chaplains and others whose employments were strictly ecclesiastical) was JM, while the functionaries were 6,853.

** This estimate was too low. A table published in the Dublin Feviriv in 1856 gave the total number excluded from the benefit of the amnesty as 262, of whom 59 had since been pardoned, leaving ioj in banishment There was, however, ‘a larger class of voluntary exiles not formally excepted from the amnesty, but who would not be allowed to enter the Papal States without special permission. The gross number is 1,273 but as of these 629 are not natives of them, the number of subjects amounts to 644. Of these, again, 152 are persons who cither have had banishment inflicted as their sentence or who have asked for it as commutation of punishment; so that the number is finally reduced to 492. Many of these cannot return, because they would immediately be arrested for common crimes; the rest are administered upon petition, if their conduct while abroad has not compromised them.’

Buying Books at Amazon Through These Links Gives Us a Commission. This Supports Our Apostolate. Thank You if You Can Help Us Like This!

Comments

comments are currently closed

3 responses to “Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 5: On the Annexation of the Papal States, Dogma of the Immaculate Conception and More”

[…] Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 5: Annexation of the Papal States […]

[…] « Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 3: The Conclave Elects a New Pope Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 5: On the Annexation of the Papal States, Dogma of the Immaculate Co… […]

[…] Pope Pius IX (found here) […]