By John R.G. Hassard

Introduction:

Here is the eighth instalment of the 1878 Life of Pius IX by John R. G. Hassard – another old Nineteenth Century Catholic book in our Tridentine Catholicism Archive. (For more about this, see our introduction to the first instalment here.)

Hassard’s book appears here in nine chapters:

- Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 1: Early Years in Christendom Despoiled

- Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 2: The Carbonari and Other Secret Societies

- Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 3: The Conclave Elects a New Pope

- Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 4: Conspiracy, War and Revolution

- Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 5: Annexation of the Papal States

- Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 6: Counter-Revolution and the Syllabus of Errors

- Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 7: Ultramontanism and the First Vatican Council

- Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 8: The Seizure of Rome and the Last Stand of the Papal Zouaves

- Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 9: A Prisoner of the Vatican

As this instalment opens, we are in 1870, immediately after the close of the First Vatican Council.

One reason for the closing of the Council is the Franco-Prussian war of that year – with the result that the last French troops defending Rome against invasion were withdrawn.

Without French support, the Papal Zouaves – forces gathered from around the world to defend the Pope – were insufficient to meet the onslaught.

Here, then Hassard tells of the fall of Rome to the Garibaldians – or put simply the forces of the emerging Italian nation, under the command at that time of General Guiseppe Garibaldi.

The reader is referred to previous instalments for the tragic details as to these twilight years of Christendom and how the erstwhile Papal States were increasingly menaced, occupied and finally usurped by Italy.

Only by an understanding of these things will it be possible to recognise how, in the last years of his life, Pope Pius IX came to regard himself as a ‘prisoner of the Vatican’.

There is also a review of a fine book about the Papal Zouaves by Charles A. Coulombe which shed further light on this history- RB.

Christendom Betrayed

His letter to the emperor has never been published, neither has the emperor’s reply, but we have the correspondence with the German king.

‘ Vicar of Christ on earth,’ wrote the Holy Father, ‘I cannot do less than offer my mediation. It is that of a sovereign who, in his quality as king, can excite no one‘s jealousy, since his territory is so small, but who, nevertheless, may inspire confidence by the moral and religious influence which he personifies.’

‘ Holy Pontiff,’ replied the king, ‘I have not been surprised but profoundly moved in reading the touch ing words traced by your hand in the name of the God of peace. How can my heart remain insensible to such a powerful appeal? God is my witness that this war was provoked neither by me nor by my people. If your Holiness could offer me, on the part of the power which has so unexpectedly declared war, the assurance of sincerely pacific dispositions, and guarantees against the renewal of such a violation of the peace and tranquillity of Europe, I certainly would not hesitate to accept them from your venerable hands, united as I am to your Holiness by the ties of Christian charity and sincere friendship.’

Later, when France was nearly crushed by the reverses of the campaign, the Pope renewed his efforts for peace.

While the government of the National Defence was established at Tours, he instructed the archbishop of that city to use all his influence against the useless prolongation of the war, and at the same time he sent Archbishop Ledochowski to Versailles to counsel moderation to the victors.

Meanwhile, the four or five thousand French troops left in Rome after the last Garibaldian invasion had been promptly withdrawn by Napoleon, not because he supposed he wanted them for when he gave the order he was just setting out ‘with a light heart ‘on his march to ruin but because he wished to please the Italian Government.

‘The political necessity is evident,’ wrote M. de Gramont; ‘we must conciliate the good dispositions of the cabinet of Florence.’ Deceived in everything, victim always of his own intrigues, Napoleon trusted to an alliance with Italy against the Prussians; he gave up the Pope as the price of it, and he got nothing in return.

Italy took the bribe, and then attached herself immediately to the other side. The troops embarked at Civita Vecchia on the 2d and 4th of August. Fighting began between the French and Prussians on the 2d, and the French met the first of their long series of defeats at Weissembourg on the 4th.

The Italian Government lost no time in tearing the Turin convention to fragments and marching in at the door which Napoleon had left open.

First came the usual complaint that the Papacy constituted a hostile government in the midst of the kingdom, a focus of disorder, a constant danger to the state.

Then, on the 8th of September, Victor Emmanuel sent a letter to the Pope by the hands of Count Ponza di San Martino, and at the same time the Italian troops prepared for the invasion of the pontifical territory.

‘Most Holy Father,’ wrote the king:

With the affection of a son, with the faith of a Catholic, with the loyalty of a king, with the sentiment of an Italian, I address myself again, as I have had to do before, to the heart of your Holiness. A storm full of perils menaces Europe.

The party of the international revolution grows bolder and more audacious, and is preparing, especially in Italy and in the provinces governed by your Holiness, the last blows against monarchy and the popedom.

I find it imperatively necessary, for the security of Italy and the Holy See, that my troops already guarding the frontiers shall advance and occupy the positions indispensable for the security of your Holiness and the maintenance of order.

Let me hope that in satisfying the national aspirations your Holiness, as the chief of Catholicity, surrounded by the devotion of the Italian populations, will preserve on the banks of the Tiber a see glorious and independent of all human sovereignty. In delivering Rome from foreign troops your Holiness will have accomplished a marvellous work and restored peace to the Church.’

‘Parliament is the servant of the Secret Societies’

The Count di San Martino was admitted to an audience, which cannot have been of the most agreeable character. He spoke of guarantees for the independence of the Church.

‘And who will guarantee me your guarantees ?’ exclaimed Pius.

‘Your king is king no longer. He can promise nothing. He is the servant of his parliament, and parliament is the servant of the secret societies; and they will cast the king down when they have no further use for him. Go, count; I will give you my answer tomorrow. I am too deeply moved with sorrow and indignation to write at present.’

The answer, dated on the 11th of September, was as follows:

‘ YOUR MAJESTY: By Count Ponza di San Martino a letter has been presented to me which your majesty has been pleased to address to me, but which is not worthy of an affectionate son who boasts of professing the Catholic faith. Into the details of that letter I do not enter, lest I should renew the pain which its first perusal caused me. I bless God, who has permitted your majes ty to bring to a climax of bitterness the closing period of my life.

As for the rest, I cannot admit certain demands nor conform myself to certain principles con tained in your letter. Again I invoke God and remit to his hands my cause, which is altogether his own. I pray him to grant many graces to Your Majesty, to free you from dangers, and alTord you the mercies which you need.’

The Italian Army Marches towards Rome

But the king had not waited for the answer. On that day the Italian army, sixty thousand strong, had crossed the frontier, and, under the command of General Cadorna, was already marching straight towards Rome.

The news of the interview with Count Ponza ci San Martino on the 10th, and the drift of his message as well as of the answer, spread rapidly throughout the city.

On the same afternoon the Pope was to inaugurate a new public fountain, and the whole population seemed to be in the streets, as if to offer a special testimonial of respect and affection. The festival in itself was nothing more than Rome was used to, but the serious circum stances of the day made it unusually impressive.

‘ Never,’ wrote a French diplomatist, ‘have I seen a demonstration so ardent and so spontaneous. The Holy Father was calm and smiling, and no one could detect upon the countenance of the noble old man a trace of those thoughts which must have sad dened his heart. I came home deeply affected by all that I had seen, and never shall I forget the fete of the inauguration of the Acqua Marcia.’

Last Stand of the Papal Zouaves

‘My children,’ said he, ‘we have two enemies one without, against whom we can promise only one thing, to do our duty; the other within, whom we can always overcome, if we will, by the grace of God. This latter is the only one we need fear. Fear sin, then, my children; and for the rest, what matters it? Nothing happens but what our dear Lord wills.’

A triduum was ordered at St. Peter’s to beg the divine mercy upon the city of Rome. The French observer whom I have just quoted writes of the last day:

We have all seen and admired the glorious ceremonies of Christmas and Easter in this great basilica of St. Peter, but what are they by the side of the humble demonstration of the triduum on the 15th of September, 1870? All Rome was there, kneeling on the pavement of the church and chant ing the litanies, of which the Pope intoned each versicle. It is the truest manifestation of the Catholic faith that I have ever been allowed to witness, and we all felt ourselves moved to the bottom of our hearts while listening to the strong voice of the old Pope, begging of Heaven to protect the city of Rome and to bless its inhabitants.’

Arms were secretly distributed by the Italian authorities within the city, and every device was employed to provoke a rising, but in vain.

The Prussian ambassador, Baron von Arnim, who had been going back and forth between Rome and the Italian headquarters, openly took sides against the Pope, and even invited the diplomatic body to sign an address advising his Holiness to yield a proposal which all the ministers emphatically rejected.

On the 19th of September Cadorna appeared before the walls and gave notice that the bombardment would open the following morning.

All the pontifical troops, to the number of about ten thousand, had gradually been called in, and General Kanzler made the best dispositions possible for at least a formal defence. The following letter was addressed to him by the Holy Father on the

‘GENERAL: Now that a great sacrilege and an enor mous injustice is about to be perpetrated, and the sol diers of a Catholic monarch, without provocation, with out even the appearance of excuse, are assembled to besiege the capital of the Catholic world, I feel, in the first place, the necessity of thanking you, general, anc all our troops, for your generous conduct up to the present moment, for your marks of affection towards the Holy See, and your readiness to consecrate yourselves entirely to the defence of this metropolis. Let these words be a solemn document to testify the discipline, valor, and loyalty of the troops in the service of the Holy See.

‘ With regard, however, to the duration of the defence, it is my duty to command that the resistance consist only of a protest sufficient and no more to establish the fact of violence. As soon as a breach is effected nego tiations must be opened for the surrender of the city. At a moment when all Europe deplores the numerous vic tims of a war between two great nations it must not be said that the Vicar of Christ, however unjustly assailed, has consented to a great effusion of blood. Our cause is the cause of God, and to his hands we commit all our defence.

‘From my heart, general, I give my benediction to you and to all our troops.

Having despatched these orders, Pius went for the last time to pray in the basilica of St. John Lateran and the chapel of the Scala Santa.

He made on his knees the painful ascent of the twenty-eight marble steps from the judgment-hall of Pilate, and, having spent some time in devotion in the little sanctuary at the top, he returned, followed by the acclamations of an affectionate multitude, to the Vatican, which he was never afterwards to leave.

He had requested all the members of the diplomatic body to go to him as soon as the firing began.

Accordingly, at the first sound of the artil lery on the morning of the 20th, all the ministers except Baron von Arnim assembled in the throne- room of the Vatican. Many of the cardinals were there, the heads of religious orders, the prelates, and a number of the Roman nobility.

The Pope came out of his apartments at seven o clock, and invited the ambassadors to be present at his Mass, which he celebrated in his private chapel in the midst of the noise of the cannonade and of bursting shells, which fell even in the gardens of the Vatican. During the Mass the Litany of the Blessed Virgin was intoned by the cardinals.

After Mass, chocolate and ices were served to the guests, according to the Roman custom, while the Pope retired to his oratory. At nine o clock, having heard a second Mass and finished his prayers of thanks giving, he received the ambassadors in his study.

Baron von Arnim had now joined his colleagues. The habitual sweetness of the Holy Father’s countenance was overshadowed by a profound sadness; his speech was slow and solemn; his manner was indescribably impressive.

He addressed a few kindly words to each of the ministers individually. Then, sitting by his table, and inviting them all to sit around him, he talked for an hour in a familiar strain, losing himself occasionally in intervals of silence and abstraction, and turning involuntarily from time to time towards the windows, through which one could see the smoke of the bombardment.

He commended to the care of the ambassadors the Papal Zouaves, who were about to become prisoners, and begged their excellencies to obtain from the Italian general the most favorable terms for these gallant soldiers.

‘And my poor Canadians!’ he suddenly exclaimed, ‘who will protect them?’

He recalled many events of his past life, even repeated some of the incidents of his voyage to Chili:

Once before now the diplomatic body has assembled around me under circumstances some thing like these. That was at the Quirinal. I remember that there was not enough food in the palace to furnish dinner for all, and we sent around to the apartments of the camerieri segreti who lodged at the Quirinal to collect whatever they had. The cook made a soup of these gatherings a sort of Spanish olla podrida.

Yesterday I was at the spot where Christ was condemned. I mounted the Scala Santa; it was a hard ascent, and I had to have a support, but 1 reached the top. These are the steps which oui Lord trod when he went to judgment. In going up I said to myself: Perhaps tomorrow I, too, shall be judged by the Catholics of Italy. Filii matris meae pugnaverunt contra me. I have need of great strength, and God gives it to me. Deo gratias!

The students of the American College have asked leave to fight for me, but I have thanked them and told them to devote themselves to the care of the wounded.

Yesterday, in returning from the Scala Santa, I saw all the flags which have been hung out in Rome as a protection. There were English, American, German, and even Turkish flags. Prince Doria displayed the English colours I am sure I do not know why. When I returned from Gaeta I saw multitudes of flags hung along the route in my honour. Now it is different; it is not for me that these are flying.

Bixio, the famous Bixio, is with the Italian army. He is a general in these days. When he was a republican he intended to throw the Pope and the cardinals into the Tiber as soon as he entered Rome. In winter that would not be pleasant; in summer it would not be quite the same.

It is not the flower of society which accompanies the Italians when they attack the father of all Catholics. We have here a repetition in a small way of what the young Romans did who repaired to the camp of Caesar after the cross ing of the Rubicon.

The Rubicon is crossed now. ‘Thy will be done on earth, as it is in heaven.’

Cannons Breach the Walls of Rome: The Pope Surrenders

At this point an officer of Gen. Kanzler’s staff arrived with the news that after a severe cannonade a practicable breach had been made near the Porta Pia.

The ambassadors retired, and left the Holy Father alone with Cardinal Antonelli. In a few moments they were recalled.

There were tears in the Pope’s eyes, and he spoke as follows:

I have just given the order to capitulate. Defence is impossible any longer without a great sacrifice of life, and to that I will not consent. I do not speak to you of myself; it is not for myself that I weep, but for these poor children who can e to defend me as their father. You will take care each of his own countrymen.

There are all mentions among them; there are French especially. Do not forget, I pray, the English and Canadians, who have no one here to represent them. I commend them all to you, that you may protect them from the ill treatment which others have had to endure during the past years.

I release my soldiers from their oath of fidelity, and leave then perfectly free. As for the conditions of the capitu lation, you must see Gen. Kanzler, with whom everything is to be arranged.’

The Italian army, entering by the Porta Pia, was followed by a large number of civilians represented to be political exiles returning to their country. An eye-witness belonging to the diplomatic body thus describes the scene:

I followed this body of men composed of three or four thousand revolutionists, recruited in every corner of Italy.

It marched in pretty good order, and without shouting, through the whole length of the Via di Porta Pia; but when they reached the piazza of the Quirinal those newly arrived were joined by their brethren and friends in Rome, commanded by a certain Marquis del Gallo, brother of the man who married one of the Bonaparte family.

The emigrants learned then that they had nothing more to fear from the ponti fical soldiers, who were prisoners guarded by the Italian army.

All danger having disappeared, each one took out of his pocket a tricolour cockade and a small flag, and the whole body of them, shouting and vociferating, directed their steps to wards the Capitol, according to the requirements of revolutionary tradition.

I was still on the piazza of the Quirinal watching this comedy when I saw a personage arrive on horseback, all bedizened with gold and decorations, before whom the crowd was respectfully bowing; it was the Baron von Arnim returning from the Villa Albani [Cadorna’s head, quarters], and having made also his triumphant entry by the breach, mounted on the horse of an Italian soldier.

‘Behold, said I to myself, the compact sealed between Prussia and the Italian revolution. In the Corso I found again my own Paris of the great days of the revolution; nothing was wanting to complete the picture men with sinister faces armed with muskets taken from the pontifical prisoners, others armed with pikes and daggers, then demonstrations, cries in short, a genuine revolutionary orgie. *

The prisoners, after marching out with the honours of war, the officers retaining their side-arms, were massed for the day in the Leonine City, or that part of Rome on the south side of the Tiber, including St. Peter’s and the Vatican; thence they were to be transported on the 21st to Civita Vecchia the foreigners to be sent home, the Romans to be removed in custody to Naples and Turin.

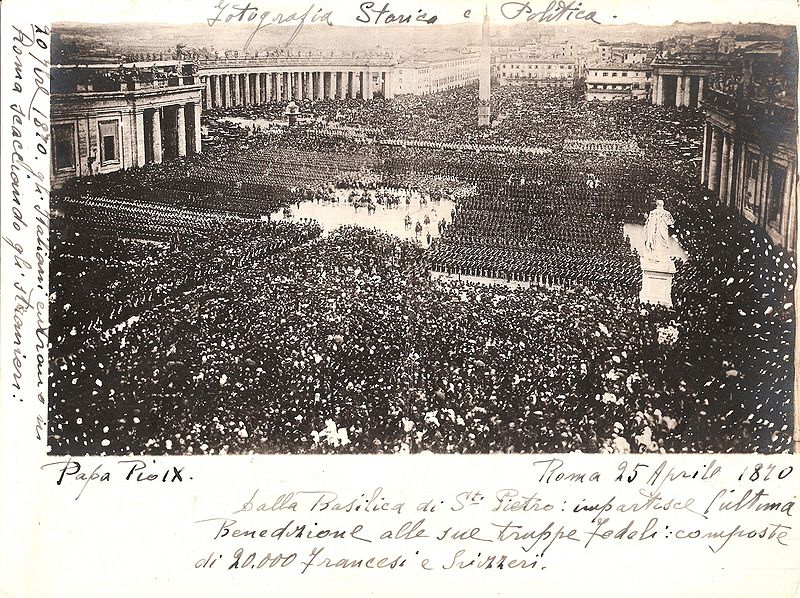

When the time came for their departure the Papal Zouaves in the piazza of St. Peter drew themselves up in a solid square, and Colonel Alet, placing himself at their head, waved his sword with the cry, ‘Long live Pius IX, Pontiff and King!’

The cry was taken up all along the ranks; hats were thrown up; vivas rent the air; a crowd of citizens who surrounded the troops and filled the balconies and windows of the neighboring houses joined in the enthusiastic cheers, and added to the picturesque as pect of the stirring scene by the waving of handkerchiefs.

The Holy Father appeared at the window of his bedchamber, and, throwing it open, stood there for a moment with his white head bare and his hands lifted in benediction. But he couid hardly pronounce the words. Overcome by emo tion, his voice choked and he fell back in the arris of his attendants.

General Kanzler, accompanied by his wife and Father Vannutelli, found him shortly afterwards, solitary and with bowed head, pacing the famous rooms enriched by the frescoes of Raphael.

‘He seemed to be suffering and exhausted to a remarkable degree,’ said Father Vannutelli, ‘but the expression of his face remained calm and full of goodness. He spoke to my sister, who burst into tears, and questioned her about the hospital, where she had passed the previous day, about the wounded, their number, the extent of their injuries, and their wants’.

‘Poor children!’ he exclaimed, ‘May Heaven reward them. This is a great crime; the punishment will fall upon the heads of those who have committed it!’

For two or three days Rome was given up to disorder. In the bombardment sixteen pontifical soldiers had been killed and fifty-eight wounded; after the surrender as many as eighty persons zouaves, priests, gendarmes, and others are said to have been assassinated in the streets of Rome.

Romans who had fought for the Pope were treated with outrageous indignity. Houses were pillaged and burned. ‘Lasciate il pnpolo sfogarsi’ said Cadorna ‘Let the people tire themselves out.’

The Leonine City was not occupied at first by the Italians; it was left without either soldiers or police, and on the 22d a mob of Garibaldians, led by a brother of one of the criminals who blew up the barracks in 1867, tried to force an entrance to the Vatican.

The pontifical gendarmes repulsed them, and one of the guards was killed. Cardinal Antonelli thereupon requested Baron von Arnim to de mand of General Cadorna the preservation of public order.

A Fraudulent Referendum

On the 2d of October the conquerors ordered a plebiscite on the question of the annexation of Rome to the kingdom of Italy. For some days previous a stream of voters, professing to be returned exiles, poured into Rome from all parts of Italy, the Government compelling the railway companies to transport gratuitously all who presented themselves with tickets supplied by any of the prefects or sub-prefects ot the kingdom.

The figures of the poll, as announced by official authority, declared that 40,785 voted yes, and 46 no!

And yet there were some thousands of civil functionaries, besides the whole body of the clergy, who were necessarily opposed to annexation.

The entire Roman nobility, with a very few exceptions, was devoted to the papal authority, and remains so to this day; a large proportion of the lower and middle classes have always been papalini; and the clerks and other employees in Government offices, museums, libraries, schools, colleges, almost all threw up their situations rather than take the oath of allegiance to Victor Emmanuel.

Under these circumstances the figures of the official declaration speak for themselves; the plebiscitum was fraudulent on its fact.

Nevertheless, Rome was promptly declared annexed to the kingdom of Italy, although it was promised in the royal decree that the Pontiff should retain ‘the dignity the inviolability, and all the prerogatives of sovereignty,’ and that a special law should provide guarantees for his independence and the free exercise of the spiritual authority of the Holy See.

The act afterwards passed by the Italian Parliament, in accordance with this promise, and known as the Law of the Guarantees, declares that:

1. The person of the Sovereign Pontiff is sacred and inviolable.

2. Any attempt against the person of the Sovereign Pontiff, or provocation to commit the same, shall be punished with the same penalties as attempts against the person of the king. The offences and insults publicly committed directly against the person of the Pontiff by speeches or acts, or by the means indicated by the first article of the law concerning the press, to be punished with the same penalties fixed by the nineteenth article of the same law.

3. The Italian Government pays to the Sovereign Pontiff within the territory of the kingdom the sovereign honors and pre-eminences accorded to him by Catholic sovereigns.

4. There is set apart in favour of the Holy See the sum of 3,225,000 lire annually [about $645,000- The Pope never accepted any part of this allowance].

5. The Sovereign Pontiff, in addition to the allowance established by the preceding article, shall continue in the enjoyment of the apostolic palaces of the Vatican and the Lateran, with all the buildings, gardens, and lands which belong to them, as well as the villa of Castel Gandolfo with its appurtenances and dependencies.’

There are also elaborate provisions for the free intercourse between the Pontiff and the episcopate, and the free exercise by the clergy of their spiritual functions.

But to say nothing of the inherent vice of the Law of Guarantees that it offered to the Holy Father as a favour a small part of what was all his by right, it was an illusive pledge which has been broken over and over again, and is likely to be still more flagrantly violated if it is not wholly repealed.

It does not even recognize the church s ownership of the little corner of Rome still occupied by the papal court. It allows the Pontiff to ‘enjoy’ the Vatican, but it claims for the Italian Government the proprietorship of that palace as well as of St. Peter s.

And I need hardly say that the pretence of suppressing ‘insults’ against the person of the Pope has been from the outset an affront to common sense. The Italian press, and the speeches of public orators, and the debates ir. the Italian Parliament have teemed with vilification, outrage, and blasphemy.

Catholicism Suppressed; Christian Rome Desecrated

Almost the first act of the new rulers of Rome was to confiscate the property of all ecclesiastical bodies and foundations whatsoever, save a very few which were exempted by name.

This left nearly the whole body of the clergy destitute, and cut off the sole support of the churches and the parish priests.

Next came the suppression of all religious orders; 50,000 persons were thus turned into the street without the means of subsistence.

The clergy were pressed into the army.

Convents, churches, charitable and religious institutions were seized and sold, or converted to the uses of the Government. Schools were broken up; education was secularized.

The revenues of most of the bishops throughout the whole kingdom were cut off, and the support of the Italian episcopate was thrown upon the Sovereign Pontiff.

The spirit of the Italian laws and the Italian administration was thoroughly and in everything anti-Catholic and anti- Christian.

All religious processions were prohibited.

The chapels and crosses which pious hands had erected in the Colosseum to commemorate the martyrs of the first centuries were torn down, and the name of Christ was chiselled off the facade of the Roman College.

Vice, violence, sacrilege, atheism everywhere followed in the track of the Piedmontese armies. They carried riot into the very churches.

A Prisoner of the Vatican

It was impossible that the Sovereign Pontiff should walk the streets of desecrated Rome, exposing himself to the affronts of a hostile multitude or the compromising protection of a usurping police. Nor is it at all certain that his person would have been safe.

Two months after the capture of Rome Monsignor de Merode, chancing to show himself at one of the balconies of the Vatican, was ordered back by one of the king’s soldiers on guard below, who pointed his musket at him.

At a later day a crowd, assembled in the piazza on the occasion of a festival, caught a momentary glimpse of the white figure of the Pope as he passed before a window.

Instantly, a cry of exultation burst forth; the square filled as if by magic, everybody shouting Viva Pio Nona!

When the troops charged upon the populace and drove them from the piazza, arresting, among other per sons, several ladies of high social position.

Having made formal protests against the invasion first in diplomatic letters, and then in a vigorous allocution, the Holy Father was compelled to choose between exile from Rome and a virtual imprisonment in the Vatican, none the less real because he was restrained by moral bonds rather than bars and chains. He decided to remain.

The reason of his choice was beautifully explained by himself to Cardinal de Bonnechose, Archbishop of Rouen. ‘I wish,’ said he to the cardinal one evening, after a private audience, ‘to give you a souvenir.’

It was a little painting on ivory, set in gold, and representing a legend of St. Peter. ‘This,’ said Pius, ‘has been the frequent subject of my meditations for several years. When the Prince of the Apostles was fleeing from persecution at Rome he met not far from the gate of St. Sebastian the figure of our Lord carrying his cross and bow ed with sadness. Doinine, quo vadis? Lord, whither goest thou? cried Peter. < I go to Rome, said Jesus Christ, to be crucified again in thy place, because thou lackest courage. Peter under stood, and remained at Rome. I shall do the same; for if I were to quit the Eternal City at this moment it seems to me that our Lord would make to me the same reproach. Perhaps the story is at bottom only a pious legend, but for me it is a definite instruction.’

*Let PienwHtais d Rome. Par Henry d Ideville. Paris.

Buying Books at Amazon Through These Links Gives Us a Commission. This Supports Our Apostolate. Thank You if You Can Help Us Like This!

Comments

comments are currently closed

One response to “Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 8: The Seizure of Rome and the Last Stand of the Papal Zouaves”

[…] Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 8: The Seizure of Rome and the Last Stand of the Papal Zouaves […]