By John R.G. Hassard

CJS. org Introduction:

Here is the ninth instalment of the 1878 Life of Pius IX by John R. G. Hassard – another old Nineteenth Century Catholic book in our Tridentine Catholicism Archive. (For more about this, see our introduction to the first instalment here.)

Hassard’s book appears here in nine chapters:

- Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 1: Early Years in Christendom Despoiled

- Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 2: The Carbonari and Other Secret Societies

- Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 3: The Conclave Elects a New Pope

- Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 4: Conspiracy, War and Revolution

- Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 5: Annexation of the Papal States

- Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 6: Counter-Revolution and the Syllabus of Errors

- Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 7: Ultramontanism and the First Vatican Council

- Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 8: The Seizure of Rome and the Last Stand of the Papal Zouaves

- Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 9: A Prisoner of the Vatican

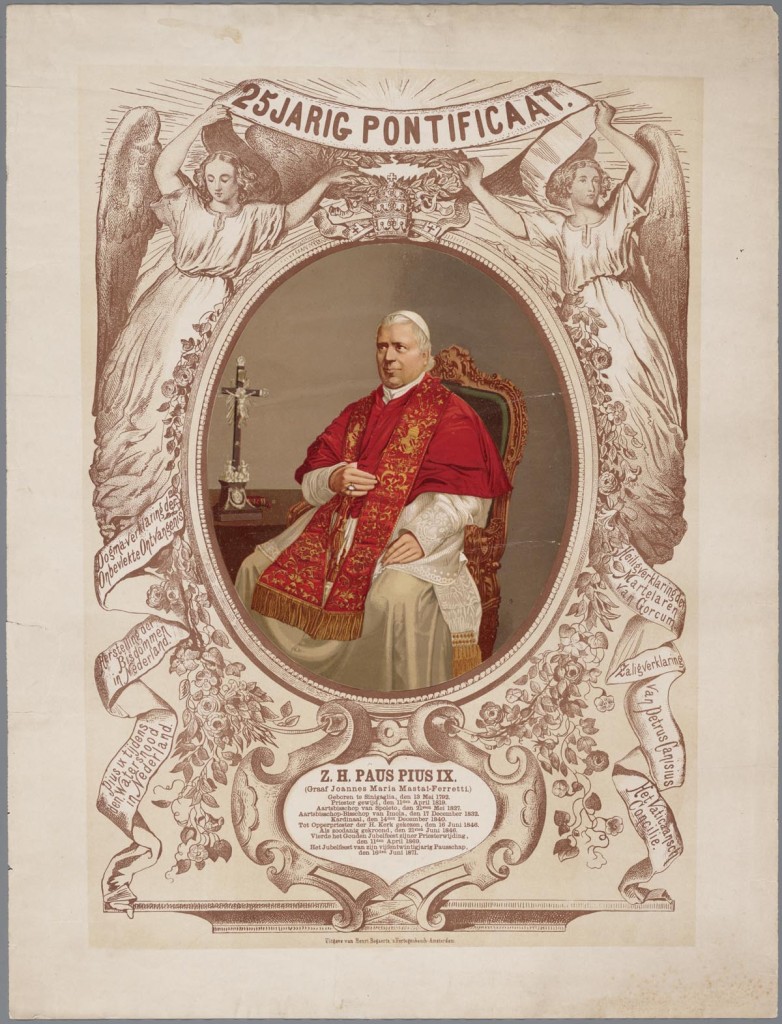

This chapter deals with the last eight years of the life of Pope Pius IX from 1870 to 1878.

These are his years when he regarded himself as a ‘Prisoner of the Vatican’ – after Rome was conquered and occupied by the emergent Italian nation, headed by King Victor Emmanuel.

The reader is referred to earlier instalments to understand how this tragic situation arose.

However, let us briefly refer to last time, where Hassard describes the situation of the Church in the immediate years after 1870, when Rome was annexed by Italy:

Almost the first act of the new rulers of Rome was to confiscate the property of all ecclesiastical bodies and foundations whatsoever, save a very few which were exempted by name.

This left nearly the whole body of the clergy destitute, and cut off the sole support of the churches and the parish priests.

Next came the suppression of all religious orders; 50,000 persons were thus turned into the street without the means of subsistence.

The clergy were pressed into the army.

Convents, churches, charitable and religious institutions were seized and sold, or converted to the uses of the Government. Schools were broken up; education was secularised.

The revenues of most of the bishops throughout the whole kingdom were cut off, and the support of the Italian episcopate was thrown upon the Sovereign Pontiff.

The spirit of the Italian laws and the Italian administration was thoroughly and in everything anti-Catholic and anti-Christian.

All religious processions were prohibited.

The chapels and crosses which pious hands had erected in the Colosseum to commemorate the martyrs of the first centuries were torn down, and the name of Christ was chiselled off the facade of the Roman College.

Vice, violence, sacrilege, atheism everywhere followed in the track of the [Italian] armies. They carried riot into the very churches.

It was impossible that the Sovereign Pontiff should walk the streets of desecrated Rome, exposing himself to the affronts of a hostile multitude or the compromising protection of a usurping police. Nor is it at all certain that his person would have been safe.

On another note, we mentioned at the outset of this series, that Hassard’s manuscript has been very slightly altered by us. An Afterword follows at the bottom of this post for anyone interested in the minutuae of these changes.

There seems little more to say at this point. Clarification of the following is best found by turning to the preceding chapters.

There is, however, another webpage at this site which can aid understanding of this epoch. It is our review (here) of The Pope’s Legion – a remarkable book by Charles A. Coloumbe which serves admirably to introduce the reader to this lost, forgotten world of the 1860s and 70s.

But now let us turn to Hassard as he examines the twilight years of Pope Pius IX – as well as the twilight of Christendom – RB.

In the Twilight of Christendom

IN the seclusion of the Vatican the life and character of Pius IX seemed more beautiful than ever. His firmness and courage increased with the growing hostility of the world; his benign and loving disposition was only sweetened by trials. A charm, always fresh, irradiated his serene countenance.

He grew more and more fascinating in the eyes of men as he daily drew closer to God.

The simple habits which he had established at the begin ning of his pontificate were continued to the end.

In the palace of eleven thousand rooms he reserved only two for his own use. The small sleeping- chamber had a bare stone floor, an iron bedstead, a hard mattress, a prie-dieu, and little or nothing else. The cabinet, or study, was furnished with equal plainness, and its walls were hung with common paper.

He rose, summer and winter, at half-past five, shaved himself, and then went to his private oratory, where he spent half an hour before the Blessed Sacrament. Then he said Mass.

Afterwards he heard a second Mass, and remained for some time in thanksgiving. If he was prevented by sickness from offering the Holy Sacrifice, one of his chaplains always celebrated in his presence and gave him communion. About nine he took a cup of black coffee or a little thin soup.

The rest of the morning was devoted to work, either alone or with the cardinal-prefects of congregations, who conferred with him on set days about the affairs of the universal Church.

General audiences, to which almost any respectable person could obtain admis sion by introduction, were held about noon. A little exercise in the garden sometimes followed, the physicians strictly requiring him to take the air at least twice a day.

So imperatively was this rule demanded by the condition of his health that in his latter years, when a humour in the leg often made him too lame to walk, a small carriage was bought and he was driven around the garden.

He dined at two o clock, having previously made a short visit to the Blessed Sacrament. The meal, which he took alone, according to the rigid etiquette of the Roman court, seldom lasted more than twenty minutes, and consisted of soup, a bit of the beef that had been boiled in it, one other dish of meat, one dish of vegetables, and fruit.

According to the universal Italian custom, he mingled a little wine with the water that he drank at dinner; it was a common white wine, bought from day to day in Rome, for he kept no cellar.

But towards the close of his life he used sometimes to take at the end of dinner, if he were more fatigued than usual, a small glass of claret, of a special vintage which the Sisters of St. Joseph at Bordeaux produced for him and called by his name.

The delicacies sent to him all found their way to the hospitals. Somebody persuaded him to try the liqueur of the Grande Chartreuse. He laughed, and, putting down the glass unfinished, said: ‘It is an excellent liqueur for the stomach of a trooper.’

Dinner was followed by a siesta of fifteen minutes, after which he read the breviary, said the rosary, and walked again either in the garden or the galleries of the Vatican. One of his favorite resorts at this hour was a beautiful alley shaded by orange-trees, where the pigeons used to feed from his hand.

He delighted to show himself quicker of foot than the cardinals who bore him company, and it was one of his pleasantries to speak of the excellent Cardinal Patrizi, who was four years his junior, as ‘that old man.’

One day, the Pope and three of the cardinals were discovered playing hide-and-seek in the garden with a little boy, the brother of one of the Noble Guards.

From five to nine he worked and gave audiences to private and official personages. Cardinal Antonelli, the Secretary of State, had apartments at the Vatican, and others were constantly there during working hours on business connected with their congregations.

Supper, consisting of soup, two boiled potatoes, and a little fruit, was served at nine; and at ten, after reciting the office and visiting the Blessed Sacrament again, the Pope retired to his chamber not always to sleep, for it is known that he often gave up a part of the night to prayer.

Such was the calm and gentle outward course of the last years of this life of battles. Some one congratulated him on his peace of soul.

‘Nevertheless,’ said he, ‘I am not made of wood.’

Sometimes, when the gates of St. Peter’s were closed for the night, he repaired to the deserted basilica, and stood in meditation before the famous statue of St. Peter, or prostrated himself in silent prayer at the tomb of the apostle, where Canova’s marble figure of Pius VI kneels in perpetual supplication.

But from the day of the entrance of the Italian troops into Rome, the magnificence of the papal ceremonial at St. Peter’s vanished, and the Pope never appeared publicly in his own church.

The Pope Refuses to Legitimise the Usurpation of Rome

Many attempts were made by the Italian Government to establish relations with the Vatican, in order to secure at least an indirect and apparent sanction of the occupation of Rome - but the Pope repulsed all such insincere advances.

He would do nothing to compromise the claims of the Holy See. He refused audiences to all the messengers who came to him from time to time on the part of the king, and he never would consent that any diplomatic representative should be accredited both to the Vatican and the Quirinal.

One morning, at the early hour of seven, the Emperor of Brazil, who was then the guest of Victor Emmanuel, presented himself unexpectedly at the Vatican while the Pope was saying Mass, and asked for an audience.

He was introduced as soon as possible. ‘What can I do to serve your majesty?’ asked Pius.

‘Holy Father, I beg you not to call me majesty; here I am only the Count of Alcantara.’

‘Well, my dear count, what will you have of me? ‘

‘I wish your Holiness to let me present his majesty the King of Italy.’

The Pope rose, and answered with energy and indignation: ‘It is useless to hold such language with me. Let the King of Piedmont abjure his evil deeds and restore my states; then I will consent to see him, but not before.’

The Prince and Princess of Wales, who visited the Pope in 1872, showed more tact and better breeding than the eccentric Brazilian. They had the good taste to decline the use of Victor Emmanuel’s carriages and horses for their ride to the Vatican. The conversation of the Pope and Prince is said to have been long, animated, and agreeable.

‘I respect the English,’ said the Holy Father, ‘for they are more religious at heart than many who call themselves Catholics; when they return some day to the fold, how gladly we shall welcome this flock which has strayed but is not lost!’

The Prince and Princess smiled, and gently shook their heads.

‘Ah, my children,’ continued the Pontiff, ‘the future is always full of surprises. Who would have imagined two years ago that we should see a Prussian army in France? Your wisest heads expected a thousand times sooner to see the Pope at Malta than Louis Napoleon in London. I am much happier than those who call themselves the masters of Rome, because I have no fears for my dynasty. God takes care of it. I may be driven away for a while; but when your children and your grand children come to visit Rome, whatever may be the temporal possessions of the Pope at that time, they will see, as you do to-day, an old man dressed in white pointing out the road to heaven.’

CJS.org Note: The Prince of Wales named above later became King Edward VII of England. As King of England, he could not be Catholic without surrendering his throne - a fact that still pertains to the British monarch today.

However, in light of the above, it is striking to note that - long after Hassard wrote his book in 1878 - King Edward VII appears to have finally converted to Catholicism on his deathbed, after a visit to Lourdes in 1910! - RB.

Vatican Etiquette and Exchanges with Pope Pius IX

He received Protestants with great kindness, yet sometimes with a frank and dignified assertion of authority which must have impressed and could hardly offend them.

‘My child,’ said he to a young minister from Berlin:

You and I ought to be friends, for we are sons of the same Father and sharers in the same heritage. See, there is only one Lord, one faith, one baptism; that is what is called Catholic unity, outside of which there is only confusion and there is no salvation. It is the mis fortune of Protestants to be outside. Not that salvation is impossible among them; there are some who will reach heaven because they have lived in invincible ignorance (ask the theologians here what that means) and their lives have been pious.

They belong to the Church without knowing it. But it is hard to err in good faith here in Rome in the focus of evangelical light.

As for yourself, my dear child, seek truth with a generous heart. I say with a generous heart, for you need to seek it with the heart even more than with the intellect. You will find it. Be assured that I will help you with my prayers. But, in your turn, do you pray for the Pope, and so we shall help each other.’

All who presented themselves at the audiences were, of course, expected to conform to the etiquette of the court, and Protestants who were guilty of deliberate rudeness, as now and then some were, received a pointed rebuke.

A tutor employed in the family of Sir Augustus Paget, the British diplomatic representative at Rome, ostentatiously remained seated at a general audience when all the guests were expected to kneel.

The Pope turned to him and said: ‘My friend, you are not obliged to come here, but if you do come you must observe the proprieties, whatever sect you belong to.’

The Englishman, too proud or too obstinate to submit, left the hall. Sir Augustus Paget dismissed him as soon as he heard of the impertinence.

The Holy Father’s rebuke of two English ladies who refused to kneel when he approached them was somewhat different. He took no notice of the breach of etiquette at the time, and treated them with his customary suavity.

But in his closing address he said: ‘I will now give you my blessing, and, if there are any here who do not value the blessing of an old man, I invoke for them the blessing of Almighty God.’ The two ladies dropped upon their knees.

To certain clergymen of the English High-Church party, who seemed indisposed to follow their principles to the logical conclusion, he said: ‘You are like the bells which call the faithful to church, but never enter.’

It often happened that a majority of the guests at an audience were English and American travel lers. On one of these occasions, after speaking to each in turn, he came to an English lady, young and very timid, and asked where she was born.

‘I am twenty-four,’ she replied, too much embarrassed to understand the question.

‘I did not ask your age, but your country,’ said the Pope with a smile.

But her confusion only increased. She fell at his feet, sobbing, and cried: ‘ O Holy Father! forgive me, please forgive me. I have told a lie; I am more than twenty-four - I am twenty-five years and two months and a half.’

The Pope raised her up, and, repressing the hilarity of the company, calmed her agitation and made her promise not to lie again, even about the merest trifle.

His wit was now playful, now caustic. There was a photograph representing him under a broad and unbecoming red hat. He did not like the picture, and, when a lady asked for his autograph on a copy of it, he wrote: Nolite timere, ego sum (Fear not; it is I).’

The author of a pious biography sent his book to the Pope for approval. The Pontiff read till he came to these words: ‘ Our saint triumphed over all temptations, but there was one snare which he could not escape: he married,’ and then he threw the book from him.

‘What!’ said he, ‘shall it be written that the Church has six sacraments and one snare?’

Of a Catholic diplomatist whose conduct were at variance he said : ‘ I do not like these accommodating consciences. If that man’s master should order him to put me in jail, he would come on his knees to tell me I must go, and his wife would work me a pair of slippers.’

During the French occupation of Rome, a certain French colonel was guilty of so gross an offence against the Pope’s authority that the Holy Father demand ed his recall. Before his departure he had the effrontery to present himself at the Vatican and ask for a number of small favors, ending with a request for the Pope’s autograph.

The Pontiff wrote on a card the words which our Lord addressed to Judas in the garden : Amice, ad quid venisti? ‘Friend, wherefore hast thou come hither?’

And the colonel, who did not understand Latin, showed it to all his friends as a testimonial of the Pope’s regard, until somebody unkindly supplied him with the translation.

It is the etiquette of the Vatican that carriages with only one horse shall not enter the inner court.

This rule was enforced one day in 1867 against Baron von Arnim, and Bismarck, for purposes of his own, endeavoured to make a diplomatic scandal of the transaction, instructing the ambassador to close the legation and quit Rome instantly unless he was allowed to drive with one horse to the very foot of the papal staircase.

The Pope caused Cardinal Antonelli to write that ‘His Holiness, taking compassion on the embarrassments of the diplomatic body, would in future allow the representatives of the great Powers to approach his presence with one quadruped ‘of any sort’ ... I believe that the Prussian minister never availed himself of this permission in its full extent; he certainly did not boast of his diplomatic victory.

One of the few members of the Roman nobility who showed a disposition to coquette with the new regime attempted to speak to the Pope in a low voice and a confidential manner.

‘Sir,’ said Pius IX aloud, ‘I do not like men with two faces. I love those who show a loyal and Christian countenance, and who speak out boldly because they have no thing to hide.’

To another who was lamenting the corruption of society and the impossibility of correcting it he said significantly : ‘You are wrong; I know an excellent remedy for these evils.

‘What is it, Holy Father?’

‘Let every man begin by reforming himself.’

A soldier stopped him and complained: ‘Holy Father, I have served twenty-five years, and they will not give me a discharge. ‘

‘Well, my friend, that does not seem fair. I have not served twenty-five years yet, but they wanted to discharge me long ago. I will see to your case.’

The Abbé Chocarne begged the blessing and favour of the Pope for a society he had founded in aid of penitent prisoners.

‘Certainly,’ replied Pius; ‘I am a prisoner myself but I am not penitent.’

Continued Devotion to Pope Pius IX

The affection shown him in his dethronement by the people of Italy was always a particular consolation to him. Deputations in great numbers came from all parts of the peninsula to testify their regard, and the Romans never seemed to tire of doing him honor.

On the anniversary of the capture of Rome it was customary for the Roman nobility to present themselves at the Vatican, partly by way of renewing their protest against the invasion, partly in order to cheer the Holy Father s spirits.

He was told one day the particulars of a ball given by the king in the palace of the Quirinal.

‘We shall have to use tons and tons of holy water to purity that Quirinal when we get back,’ said he ‘we or those who come after us.’

On the 16th of June, 1871, he reached the twenty-fifth anniversary of his election to the papacy, thus falsifying, for the first time in history, the popular prediction that no pope should ‘see the years of Peter’ - a prediction which even finds a place in the ritual of consecration.

The day was celebrated by impressive services in the basilicas of St. Peter and St. John Lateran, attended by enormous multitudes of people.

Thousands of pilgrims came from Italy and from foreign lands to offer their felicitations in person, and on one of the days devoted to the observance the Pope delivered twelve addresses in answer to as many different deputations from different countries.

More than a thousand messages of compliment were received by telegraph, the first that arrived being from Queen Victoria.

Large sums of money were brought by the pilgrims; and, indeed, the generosity of the faithful towards their imprisoned bishop was always magnificent. By their contributions he was enabled to defray the cost of the administration of church affairs and the expenses of the palace and the basilica, to keep up the famous Vatican manufacture of mosaics, to grant from $125 to $200 a month to the destitute Italian bishops, according to their needs, to continue certain public works, and to provide many schools and asylums in place of those which had been destroyed or perverted to irreligious uses by the Government of Italy.

His private and personal charities continued to be enormous, as they always had been.

But none of his own family ever profited in the slightest degree by his elevation to the supreme dignity.

‘All the Nations of Christendom’

The dreadful oppression of the Church in Germany and Switzerland, the steady advance of the atheistic revolution in Italy, the persecution of Catholics in Poland and other parts of the Russian Empire with atrocities which the world as yet hardly realizes, were afflictions added to the last years of the sadly burdened Father of the Faithful.

He faced them with his habitual courage, and he laboured to correct the evils of the world with such an incessant watchfulness and untiring energy that we could hardly think of him as an old man who had outlived his own generation.

His bold and in spiring words had the ring of perpetual youth. On the 12th of March, 1877, he delivered an allocution on the subject of a proposed Law against the Abuses of the Clergy, then under consideration in the Italian Parliament, and it roused Europe like a blast of judgment.

Almost the last public act of his life was a spirited appeal to the Russian Government in behalf of the suffering Poles. He defended the Jesuits in a brief, and he gave a signal proof of his affection for their venerable society by adding two distinguished Jesuits to the Sacred College Cardinal Tarquini, who was created in 1873 and died the next year, and Cardinal Franzelin, who was created in 1876.

Never had the College of Cardinals been so truly an emblem of the catholicity of the Church as it became under his enlightened government.

All the nations of Christendom were represented in it. He gave a cardinal to Ireland. He promoted Dr. Manning to the vacant place of the lamented Cardinal Wise man, and conferred a hat upon another English prelate, Monsignor Howard. He created the first American cardinal, Archbishop McCloskey, in 1875.

He honored the misfortunes and con stancy of the Catholics of Prussian Poland by rewarding Archbishop Ledochowski with the dignity of prince of the Church, and giving him hospitality at the Vatican when he was released from his cruel imprisonment.

He was never tired of preaching the power of prayer and the duty of cheerful submission to the divine will. A French priest, in thanking him for certain favours, exclaimed: ‘Ah! Holy Father, how I shall pray for your speedy deliverance and the cessation of persecutions.’

‘Pray, rather,’ replied the Pope, ‘ that the will of God may be done. You and I do not know whether it is best that the storm should abate so quickly. Persecution is the health of the Church! It has been said that no pope ever did so much to promote the glory of God by adding to the glory of his saints.

Initiatives and Devotion of Pope Pius IX

[caption id="attachment_12683" align="alignright" width="347"] Nineteenth Century Traditional Catholic Iconography of the Sacred Heart[/caption]

Nineteenth Century Traditional Catholic Iconography of the Sacred Heart[/caption]

He placed hun dreds of martyrs and others on the calendar. He enrolled St. Alphonsus de Liguori and St. Francis de Sales among the doctors of the Church; and it is hardly necessary to remind the reader with how much zeal the Pontiff who defined the dogma of the Immaculate Conception promoted true devotion to the Blessed Virgin.

He had a special piety also towards St. Joseph, whom, by a decree of December 8, 1871, he declared patron of the universal Church.

A French artist, having received a commission to paint for the Holy Father a picture symbolizing the Immaculate Conception, submitted a sketch for his Holiness approval.

‘It is good,’ said the Pope; ‘but I do not see St. Joseph.’

The painter replied that he would represent him in a group surrounded by clouds of glory.

‘No,’ rejoined Pius, pointing to the side of Jesus Christ; ‘put him there. That is his place in heaven.’

The remarkable revival of the devotion to the Sacred Heart of Jesus during the last few years was fostered by the Holy Father with all earnestness.

He decreed the beatification of Margaret Mary Alacoque, with whose revelations the modern phase of this devotion may be said to have originated; and in June, 1875, he consecrated to the Sacred Heart the Church throughout the world.

He was careful, however, to discourage, and even sharply condemn, a variety of unauthorized and extravagant devotions, fantastic in character and now and then somewhat superstitious in tendency.

On the Greatness of Pope Pius IX

[caption id="attachment_13087" align="alignright" width="401"] Pope Pius IX[/caption]

Pope Pius IX[/caption]

In the course of this narrative I have tried to show how the exercise of the Holy Father‘s supreme authority gradually suppressed factions within the pale of the faith, dispelled the phantom of ‘national churches’, abolished all differences of theological schools, whether at Paris or at Munich, settled ancient controversies, drew close the bonds of union between the episcopate and its visible head, and marked out with startling clearness the lines of division between the anti-Christian world and the Christian Church.

But this was only half of his great work. Still more wonderful was the general revival of Catholic faith and piety under his fostering influence.

No pope in modern times has been so dear to the hearts of the people, or has so strongly impressed his personality upon the Catholic world.

Others commanded the intellectual obedience of the faithful; Pius spoke directly to their hearts.

Others were loved, perhaps, by the few thousands who lived immediately around them, Pius IX was an object of enthusiastic affection to millions all over the world.

The great movement of pilgrimages, which began soon after the Italian occupation of Rome, or perhaps may be traced to the still-earlier popular demonstrations excited by the different anniversaries which have already been mentioned in these pages, became an important agency in extending the Pontiff’s influence and hastening the Catholic revival of which he was the fervid apostle.

In organized multitudes like armies, or in small troops of private persons, or in family parties, pilgrims travelled to Rome from the four quarters of the earth, only to kneel at the Pope’s feet, to kiss his hand, to receive his blessing, and to listen to the burning words which flowed from his lips.

A Warning Regarding American Materialism

Almost every day he received travellers, and he always had something appropriate to say to them. To a deputation from the United States in 1873 he said :

I am grateful to America fcr these sincere and energetic protestations which represent, I know, the sentiments of all American Catholics, and I feel especially bound to pray for a nation so highly blessed by God in the fertility of its soil and its industrial prosperity.

Be assured that I pray God to increase and fructify these gifts; yet I warn the world that such blessings ought not to engross tlie affections of those who possess them.

North America is incomparably richer than any other country; but riches should not be its only treasure.

In the Gospel which I read at Mass this morning Jesus Christ says : Where the treasure is, there is thy heart also.

Now, America is a nation devoted to commerce and all kinds of traffic.

That is well, for every man must provide for the necessaries of life: honest traffic in what Providence has given us is permitted to all, and it is right that the father of a family should bring up his children in accordance with the exigencies of their proper state. There is not the least harm in thinking of all that.

But the love of wealth must not be carried to excess; you must not attach yourselves too much to it, nor chain the heart to the treasures of the earth.

This fatal worship of a purely material prosperity is condemned by Jesus Christ.

Our Lord himself had a modest purse; he even had an administrator, who was Judas; but you know whither Judas was carried by his immoderate love of money.

Have money, then, if you will; seek honestly to increase your store and improve the circumstances of your family; nothing is more just or more natural; but let it be only on condition that your hearts do not be come fastened to the goods of this world, and that you do not make them the object of your worship.

This is the only reflection I wish to suggest before quitting you; for the rest, I adjure you to pray to God.

Let us all pray that he will ever protect us, and give us strength and courage in the midst of the dangers and tribulations of the Church. Here we are, so to speak, over a volcano, and, alas!the government seems eager to open the crater. But God will save us.

A large body of pilgrims from the United States and Canada visited Rome in 1874. A band of nearly 8,000 Spaniards made their way thither in 1876, and the Pope received them in St. Peter’s, since there was no room in the Vatican that would hold such a multitude.

The gates of the church were closed, however, to all except the pilgrims.

In the following summer occurred the fiftieth anniversary of the Holy Father’s consecration as a bishop, and the fervor of the pilgrims reached its culmination.

The day of the commemoration proper was the 3rd of June, but from the end of April to the beginning of July a great tide of strangers, as if by a spontaneous and universal impulse, set steadily towards the Vatican.

There were seven or eight separate deputations from France, numbering in the aggregate several thousands. There were representatives of Rome and many other Italian cities. There were eleven bishops, forty priests, and about one hundred laymen from the United States. There were two bands from Canada. There were two delegations from Calcutta. There were three or four from Germany; three or more from Ireland; others from Poland, Belgium, Switzerland, Austria, Holland, Croatia, Portugal, Scotland. Three or four days were given up to Italy alone. Spain sent 1,000. England despatched an imposing body of pilgrims and an address signed by 500,000 names.

One of the German addresses was signed by 200,000 young men. Five hundred periodicals were represented by a deputation from the Catholic press. An immense number of valuable gifts were sent at the same time, and when they were displayed at the Vatican the exposition filled several spacious halls.

An American traveller, describing the appearance of the Holy Father in 1876, wrote as follows:

At the reception of the Spaniards to-day it was generally remarked that the Pope looked wonderfully well and strong. His general health is beyond doubt good, although, as he recently said of himself, ’One cannot be an octogenarian with impunity’.

When I first saw him, at the audience I have described above, I found in his face and figure as he entered the room marks of infirmity for which I was not prepared. He looks much older than any of his pictures, if I except a single recent photograph, which I believe is not known in America.

His lower lip droops a little, his eye has lost much of its lustre, his head hangs over, and his step is uncertain. His voice, too, at first was tremulous and broken.

But in a few minutes my impressions of his condition were greatly changed. In conversation his whole face lighted up, his speech was firm, his manner was vivacious, he looked no longer a feeble old man of 84, but a hale and well preserved gentleman of 70.

When he raised his voice to address the whole assemblage the tones were strong and musical, the articulation beautifully clear. He made gestures freely with both arms, and I noticed that his hand was as steady as if he had nerves of iron.

Alarming reports of his impending dissolution often reach the papal court from America and elsewhere but the Pope’s friends laugh at them.

When I look over certain of the Italian journals with out finding the news of my last illness and death, said Pius IX lately, it always seems to me as if they had forgotten something. So far as anybody can see, his chances of living several years longer are very fair.

Final Days of Pope Pius IX

But by the end of the year 1877 it became evi dent that the last hours of this heroic life were near at hand. On the 21st of November he received a band of pilgrims from Carcassone, in France, and addressed them at considerable length and with unusual emotion.

After this exertion, he was for nearly a month confined to his room by fever, and the wounds in his leg became enlarged. He recovered so far as to resume all the duties of his office, and to give audiences daily to the cardinals and prelates, and to others who had important business with him; but as a matter of prudence the general audiences were discontinued.

It was impossible for him to say Mass, and an altar was consequently placed in the room adjoining his bed chamber, where a chaplain celebrated the Holy Sacrifice every morning, and the Pope, lying where he could see the service through the open door, received the Blessed Eucharist.

A portable bed was contrived, in which he was carried from his chamber to his library. Thus, pillowed on his couch, his mind clear and active, his temper serene and cheerful, his venerable face radiant with love, he sank gently to his rest. On the 28th of December the cardinals met in consistory around his bed in the library, and he delivered his last allocution :

VENERABLE BRETHREN: Your presence to-day in such numbers gives us the opportunity which we gladly seize to return you and each of you our sincere thanks for the kind offices shown us in this time of our illness. We thank God that we have found you most faithful helpers in bearing the burdens of the aposiolic ministry, and your virtue and your constant affection have contributed to lessen the bitterness of our many sufferings.

But much more we rejoice in your love and zeal. We cannot forget that we need daily more and more your co-operation, and that of all our brethren and of the faithful, to obtain the immediate aid of God for the many necessities which press upon us and upon the Church.

Therefore we urgently exhort you, and especially those of you who exercise the episcopal ministry in our dioceses, as well as all the pastors who preside ever the Lord’s flock throughout the Catholic world, to employ the divine clemency, and cause prayers to be offered up to God that he may give us amidst the afflictions of our body strength of mind to wage vigorously the conflict which must be endured, to regard mercifully the labors and wrongs of the Church, to forgive us all our sins, and for the glory of his name to grant us the gift of good-will and the fruits of that peace which the angelic choirs announced to mankind at the Saviour s birth.

Forgiveness of Victor Emmanuel

Victor Emmanuel died on the 9th of January, 1878.

All the tenderness of the Pope’s heart was called out by this sudden event. As soon as the king’s danger was known, Pius IX sent Monsignor Marinelli, sacristan of the Apostolic Palaces, to offer the dying man the consolations of religion, and to bear a message of forgiveness and fatherly kindness.

Refused entrance by the officials of the court, the messenger was despatched again on the two following days, and was at length admitted on the third visit.

In his last hours Victor Emmanuel reconciled himself with the Church by a declaration, into whose sufficiency the Holy Father had no disposition to enquire too closely.

‘Let us show all possible pity,’ said the Pontiff. The censures were removed, the last sacraments were administered, and the churches were opened for the funeral services and requiems.

On the Feast of the Purification, February 2, the Pope was well enough to be carried to the throne- room, where he received the customary presentation of candles from the heads of chapters, colleges, and religious orders, and the parish priests of Rome, and delivered an impressive discourse without apparent fatigue. The next day he was bright and cheerful, and even able to walk a little.

Death of Pope Pius IX

In the night of Wednesday, February 6, he suddenly became feverish and strangely feeble. At three o clock on Thursday morning the physicians ad ministered a restorative, which revived him for a little while, but at half past four he was seized with a fit of shivering, accompanied by difficulty of breathing, and his condition was pronounced alarming.

At half-past eight, Monsignor Marinelli administered the Viaticum, and half an hour later he gave Extreme Unction.

From that time the Holy Father grew rapidly worse; but amidst all his pain and weakness he was perfectly conscious, calm, and happy. Just before noon he took his crucifix from beneath his pillow and blessed those who were kneeling around him Cardinals Bilio, Manning, Howard, and Martinelli, and several of the domestic prelates and officers of the palace.

Cardinal Bilio, the grand penitentiary, took his position by the bedside and never left it till the end. The prayers for the dying were now recited by the cardinals, and Pius, though with great difficulty, joined in them audibly, adding In domum Domini ibimus - (We will go into the house of the Lord).’

When Cardinal Bilio came to the words, Proficiscere ‘Depart, Christian soul’ he paused.

‘Si, proficiscere’ (Yes, depart)’ said the Pontiff. These were his last words.

His breathing became more painful, but his mind was still clear, and he made signs of regret that he could not speak.

About two o’ clock, Cardinal Bilio begged him to bless the Sacred College, and he lifted his right hand and blessed them.

Almost immediately afterward he became unconscious.

Nearly all the cardinals in Rome, and a great number of bishops and other ecclesiastics, were kneeling in the antechamber. At half-past five Cardinal Bilio began to recite the sorrowful mysteries of the rosary, but before he had finished the death-rattle was heard, and just at the hour of the Ave Maria the soul of Pius the Great was taken to the arms of God.

According to custom the body was embalmed, and lay in state during the following Sunday, Monday, and Tuesday in the chapel of the Blessed Sacrament in St. Peter’s, where an immense concourse of people passed before it.

On the night of Wednesday, the 14th, the final ceremonies of the funeral took place within the closed and barred basilica, and the coffin was deposited in the plain sarcophagus over a door in the chapel of the choir, where the remains of every pope in turn repose during the reign of his next successor.

There for thirty-two years had rested the bones of Gregory XVI, and there a marble slab now bears the inscription: PIUS IX., P.M.

His will left directions for his final interment. It was to be in the ancient patriarchal church of St. Lawrence-outside-the-Walls, one of the ‘seven churches of Rome’ to which pilgrims in the primitive ages resorted from all parts of the West.

‘My body shall be buried,’ reads the will, ‘just under the little arch which is over against the graticola, or stone, on which are still to be seen the stains produced by the martyrdom of the illustrious Levite.

The expense of the monument must not exceed four hundred scudi; on it shall be carved the tiara and keys; the only armorial device shall be a skull; and the epitaph is to be Ossa et cineres Pii IX, Sum. Pont., vixit an . . . in Pontificate an . . . Orate pro eo (The bones and ashes of Pius IX, Supreme Pontiff, who lived . . . years, in the Pontificate . . . years. Pray for him).’

CJS.org Afterword

In our introduction to this series, we mentioned that ‘very small changes have been introduced into the manuscript, including things like adding italics and subtitles and breaking long paragraphs down into shorter ones.’

To expand, the small changes have been dictated by considerations of accessibility for a modern audience. This is why, for example, very long Victorian paragraphs have been broken into very short ones of even a single sentence.

For in these days of reading from computer monitors, I believe this approach of adding copious ‘white space’ to be a most helpful one. (At least to ageing eyes like my own!)

To give another example, while some italicisation occurs in the original text, much more has been added here - often to draw the reader's eyes to historical events and personalities that might otherwise get lost in the welter of now-unfamiliar detail.

For again, whilst those events and personalities were common knowledge in 1878 when Hassard's book first appeared, they are not so today.

In addition to the above, there have been a few very small cuts in the text usually indicated either by ... to indicate lacunae or brackets with text added by myself.

In a few cases, however, I have made minuscule changes with no indication of my own hand. These include very small matters like changing terms like Sardinia or Piedmont to Sardinia-Piedmont - again to help the modern reader understand that what appear two political entities (Sardinia and Piedmont) are really one. Again, such things were commonly known at the time.

And there are other similar substitions of more modern terminology to aid understanding.

I have also changed punctuation at times - adding commas and even breaking down long Victorian sentences divided by often-tedious semi-colons into shorter sentences in their own right.

The subtitles are entirely my own and original chapter divisions have been removed.

All other changes seem to me minuscule indeed and have been implemented not to change the author's meaning, but simply to make it more possible for the modern reader to understand the author's meaning - RB.

Buying Books at Amazon Through These Links Gives Us a Commission. This Supports Our Apostolate. Thank You if You Can Help Us Like This!

Comments

comments are currently closed

2 responses to “Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch. 9: ‘A Prisoner of the Vatican’”

[…] Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 9: A Prisoner of the Vatican […]

[…] Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 9: A Prisoner of the Vatican […]