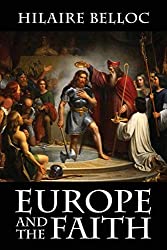

This is a piercing, prophetic set of essays by a great Catholic thinker.

For the essays were probably largely written in the 1920s – although collected into book form in 1931. And yet how very prescient, how very pertinent they are with regard to the world of today!

This time, we will look at Belloc and these Essays in considerable depth.

This is partly because, so far, our reviews of Belloc’s books, such as Survivals and New Arrivals or Economics for Helen have been relatively short.

It is also because, more and more at this website, we realise our deep indebtedness to this great man and we would introduce him to people who care about the same things we do.

And Essays of a Catholic can serve as an especially fine introduction – not just to Belloc, but, truly, many of the things I aim for in my weblog.

Because so much of my writing concerns the threat to the world of de-Christianisation, materialism, unbridled capitalism, New Age neo-paganism and more.

And how I see that, long ago, Belloc prefigured so much of what I try to say – and clearly said it much, much better than I ever could.

Hilaire Belloc is not a saint, but if he were, how tempted would I be to make him a patron saint of this site!

On the Life-Force of Western Civilisation

But let us return to the Essays – which, as I say, can serve so well to introduce Belloc’s thinking. At the beginning of the book, Belloc makes a bold statement that is, in many ways, paradigmatic, for everything which then follows after:

Our civilisation developed as a Catholic civilization. It developed and matured as a Catholic thing. With the loss of the Faith it will slip back not only into Paganism, but into barbarism with the accompaniments of Paganism, and especially the institution of slavery.

It will find gods to worship, but they will be evil gods as were those of the older savage Paganism before it began its advance towards Catholicism.

The road downhill is the same as the road up the hill. It is the same road, but to go down back into the marshes again is a very different thing from coming up from the marshes into pure air.

All things return to their origin. A living organic being, whether a human body or a whole state of society, turns at last into its original elements if life be not maintained in it. But in that process of return there is a phase of corruption which is very unpleasant. That phase the modern world outside the Catholic Church has arrived at.

What Belloc is saying is that the life of Western Civilisation IS the Church.

Now, Belloc was writing in a pre-Vatican II Catholicism which identified the Church purely and simply with Catholicism.

But our recent, mourned and beloved Holy Father, Pope Benedict XVI would say things a little different than Belloc has just put it.

For the teaching of Benedict’s magisterium is that the Holy Church of Christ cannot be precisely identified with the Catholic Church.

No, the Mystical Body of Christ is something that exists most fully within Catholicism. Yet it also exists to a great measure within the Orthodox Churches.

The recent magisterium of the Church has also stated that the Holy Mystery of the Church expresses itself, in some measure, through the Protestant confessions as well – although not so much that these can or should be called ‘Churches’. (According to the magisterium of the Church, they are more properly referred to as ‘Ecclesial Communities.’)

In respecting the contemporary magisterium of the Church, let us then slightly recast Belloc’s opening volley.

The life of Western Civilisation is the Church. It is the Living Mystery of the Church of Christ – expressed in both Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy – that has produced the healthy, living functioning of the Western world.

Without it, the whole state of society begins to decompose and die …

This thesis – so provocative to the modern mind – is at the heart of these essays.

And let us make a little digression. How much Belloc’s thinking here parallels that of another great inspiration for this site, Valentin Tomberg, who wrote:

The sickness of the West today is that it is more and more lacking creative élan. The Reformation, rationalism, the French revolution, materialistic faith of the nineteenth century, and the Bolshevik revolution, show that everywhere mankind is turning away from the Virgin.

The consequence of this is that the sources of creative spiritual élan are drying up, one after the other, and that an increasing aridity is showing up in all domains of the spiritual life of the West.

It is said that the West is growing old. But why? Because it lacks creative élan, because it has turned away from the source of creative elan, because it has turned away from the Virgin.

How Hilaire Belloc would have concurred! For he loved the Blessed Virgin dearly and, like Valentin Tomberg, he saw that the Reformation had rejected Our Mother, the Church and that here the problem began …

Hilaire Belloc regards the New Paganism

But to come back to the Essays, we see that the book turns on two types of civilisation – the first animated by the Church (and in Western Europe and the Americas this is first and foremost the Catholic Church) and a second type of civilisation, which Belloc calls the new Paganism.

The New Paganism, as it happens, is the first essay in this collection and it is worth turning to, in order to see what Belloc means by the term:

We call Paganism an absence of the Christian revelation. That is why we distinguish between Paganism and the different heresies; that is why we give the name of Christian to [Protestants], who only possess a part of Catholic truth …

For a Christian man or society is one that has some part of Catholicism left in him. But when every shred of Catholicism is lost we call that state of things “Unchristian.”

Now, it must be evident to everybody by this time that, with the attack on Faith and the Church at the Reformation, the successful rebellion of so many and their secession from United Christendom, there began a process which could only end in the complete loss of all Catholic doctrine and morals by the deserters.

That consummation we are today reaching.

It took a long time to come about, but come about it has. We have but to look around us to see that there are, spreading over what used to be the Christian world, larger and larger areas over which the Christian spirit has wholly failed; is absent.

I mean by ‘larger areas’ both larger moral and larger physical areas, but especially larger moral areas.

There are now whole groups of books, whole bodies of men, which are definitely Pagan, and these are beginning to join up into larger groups. It is like the freezing over of a pond, which begins in patches of ice; the patches unite to form wide sheets, till at last the whole is one solid surface.

There are considerable masses of literature in the modern world, of philosophy and history (and especially of fiction), which are Pagan and they are coalescing — to form a corpus of anti-Christian influence.

It is not so much that they deny the Incarnation and the Resurrection, not even that they ignore doctrine.

It is rather that they contradict and oppose the old inherited Christian system of morals to which people used to adhere long after they had given up definite doctrine.

This New Paganism is already a world of its own. It bulks large, and it is certainly going to spread and occupy more and more of modern life.

It is exceedingly important that we should judge rightly and in good time of what its effects will probably be, for we are going to come under the influence of those effects to some extent, and our children will come very strongly under their influence [Italics mine].

Those effects are already impressing themselves profoundly upon the Press, conversation, laws, building, and intimate habits of our time.

Scary Stuff: Belloc on being a Catholic

Belloc, then, is pitting two forces against each other: the new, growing corpus of anti-Christian influence as he puts it – and Catholicism.

As Belloc has it, a choice must be made – a choice between which type of authority one chooses to submit to.

For we all make this choice – whether consciously or unconsciously.

In the past people chose – whether consciously or unconsciously – Christendom.

Today, they are choosing – whether consciously or unconsciously – that which marginalises Christ and His Church. As Belloc writes:

All men accept authority. The difference between different groups lies in the type of authority which they accept. The Catholic has arrived at the conviction, or, if you will, has been given and has retained the conviction (some come in from outside; some go outside and come back again; most receive the Faith by instruction in youth, but test it in maturity by experience) that there has been a Divine revelation.

He discovers or recognizes a special action of God upon this earth over and above that general action which all who are not atheists admit.

He discovers or recognizes a certain personality and voice — that of the Catholic Church — which conforms to the necessary marks of holiness and right proportion, and the ramification of doctrine from which is both consistent and wholly good.

The incarnation of the Deity in the Man Jesus Christ, the immortality of the human soul, its responsibility to its Creator for good and evil done in this world, its consequent fate after death, the main rite and doctrine of the Eucharist — these and a host of other affirmations are not dissociated, but form a consistent whole, which is . . . the sole full guide to right living in this world [Italics mine].

Belloc goes onto say that:

To take up that position is to be a Catholic. To doubt it or deny it is to oppose Catholicism.

And he realises how dreadful this is – in the true sense of being filled with dread:

But that position is taken up under the fierce light of reason. It is indeed puerile to imagine that it could be taken up under any other light.

A proposition so awful and so singular is not accepted blindfold; it is of its very nature subject to instant inquiry [Italics mine].

It is not a thing to be taken for granted, as are ideals which all accept as a matter of course.

On the contrary, it is of its very nature exceptional, unlikely, and not only requires examination before it can be accepted, but an act of the will.

Nor is it true, as men ignorant of history pretend, that in barbaric and uncritical times (of which they think the Faith a survival) these truths were accepted without inspection, and that the argument from reason is a modern one.

Throughout the ages from the first apologetic of the Church in the second century to the present day, without interruption throughout the Dark Ages and later throughout the Middle, and all through the high intellectual life of the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries, the appeal to reason by Catholics has been universal and continuous.

Today, in the twentieth century, Catholics are the only organized body consistently appealing to the reason and to the immutable laws of thought as against the a priori conceptions of physical scientists and the muddled emotionalism of ephemeral philosophic systems.

I think here, dear Reader, to Bl. John Paul II, who at the beginning of his pontificate cried out: Be not afraid!

For it is scary, scary stuff to be a Catholic.

What St. John Paul II and Hilaire Belloc are both saying is that there is a choice to be made – or ‘an act of the will’ of Belloc has it.

One must choose between the Church of Christ or the world outside the Church of Christ. In the West, this is obviously the world of secularism and the New Age. The New Age had, of course, not yet arrived when Belloc wrote in the Twenties – although Belloc foretold much about it.

But what I call Secular Materialism at this website was already a powerful, growing force even in the 1920s – even if it was nothing like it is today. Belloc was clear how irreconcilably opposed this was to Christian and Catholic faith – and saw the danger.

The Catholic Church and the Modern State

This fundamental opposition between modernity and the Church of Christ is perhaps nowhere more explicit in these essays than in one specifically devoted to Church and State. (And as an aside, we say that those who know Valentin Tomberg’s legal-political writings will see many parallels here.)

Here Belloc does what Belloc does best: confront the truth of things head-on.

Nearly ninety years after Belloc wrote these words, we still find many souls thinking that Catholicism and secular modernity can be reconciled.

That was an illusion in the Twenties and it is even more demonstrably an illusion. Prophetically, Belloc tells us why:

The claims of the Catholic Church being universal, tend to conflict with the claims of the modern laical, absolute State, which are particular.

Perhaps my opponents will quarrel with my using the terms “laical” and “absolute.” “Laical” I can defend as meaning the conception that the Modern State is not allowed by its principles to adopt or support anyone defined and named transcendental philosophy or religion. On this point I think all will agree with me.

The Modern Electoral State does indeed always and inevitably support one general religious attitude and oppress its opposite very strongly, but by implication only, and indirectly; it would be shocked if it were accused of doing even that; and a defined and named religion it does not and, consistently, cannot openly adopt.

As for the word “absolute,” I do not use it in the sense of “absolute government,” but in the sense that the Modern Civil State, like the old Pagan Civil State of antiquity (to which it is so rapidly approaching in type), will brook no division of sovereignty.

Its citizens are required by it to give allegiance to the State alone, and to no external power whatsoever. I think my opponents will also agree with me in this sense of the word “absolute.”

The Modern State differs from the Medieval State in that it claims complete independence from all authority other than its own, whereas the Medieval State regarded itself as only part of Christendom and bound by the general morals and arrangements of Christian men.

This absolutism of the Modern State began in the sixteenth century with the affirmation of the Protestant princes that their power was not responsible to Christendom or its officers, but independent of them.

It had its immediate fruit in what was called “The Divine Right of Kings,” whereof the claim of a modern government, whether monarchical, republican or whatnot, to undivided allegiance is the heir.

In my judgment, a conflict between the State claiming unlimited powers and the Catholic Church is inevitable. Whether the State be “Modern” or no, seems to me quite indifferent.

Whether it be Democratic — as some small States can be; Oligarchic — as are all States dependent on elected bodies; or Monarchic — governed by one president or king, elected, imposed, or hereditary — the Civil State is always potentially in conflict with the Catholic Church.

And when the Civil State claims absolute authority for its laws in all matters, then it will inevitably come sooner or later into active conflict with the Catholic Church.

That Catholicism in its midst is an alien thing is perfectly true. That men should dread its moral influence as something which disintegrates that Protestantism or Paganism which is the soul of their society is natural and inevitable [Italics added].

Hilaire Belloc on Capitalism

All this I find deeply refreshing. Belloc is pugnacious, admittedly – he wants to throw a bucket of water over a society soundly, stubbornly asleep.

‘WAKE up! The world is on fire!’ Or the world is fatally compromised and is in danger of dying.

This is what I hear behind Belloc’s buckets of water …

In another essay, Belloc moves from the political to the economic, seeing that, of course, our secular modern state is inextricably bound up with capitalism – and that the two together are like bastard twins born of the divorced state of Christendom:

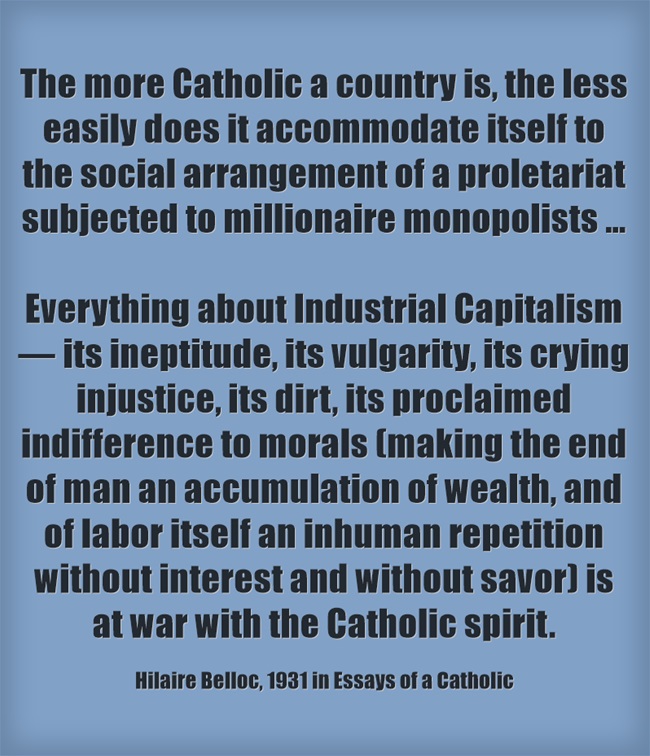

No one will doubt that Catholicism is in spirit opposed to Industrial Capitalism; the Faith would never have produced Huddersfield or Pittsburg.

It is demonstrable that historically, Industrial Capitalism arose out of the denial of Catholic morals at the Reformation.

It has been very well said by one of the principal enemies of the Church, and said boastfully, that Industrial Capitalism is the “robust child” of the Reformation and that the vitality of the effect proves the enduring strength of the cause.

It is equally clear that the more Catholic a country is, the less easily does it accommodate itself to the social arrangement of a proletariat subjected to millionaire monopolists.

Industrial Capitalism as a point of historical fact the product of that spirit which destroyed the Faith in men’s hearts and eradicated it from society — where they could — by the most abominable persecutions; but, also in point of historical fact, Industrial Capitalism has arisen late in societies of Catholic culture, has not flourished therein, and, what is more, in proportion as the nation is affected by Catholicism, in that proportion did it come tardily to accept the inroads of Industrial Capitalism and in that proportion does it still ill agree with Industrial Capitalism.

That is why the more Catholic districts of Europe have in the past been called “backward”; and that is why there is a fiercer class war in the industrial plague spots of Catholic Europe than in the great towns of Protestant Europe.

In France, one of the main reasons why the anti-Catholic minority, especially the anti-Catholic of the Huguenot [French Protestant] type, plays so great a part in the economic control of the country is that he has been the pioneer in introducing the mechanics of Industrial Capitalism.

In Spain, Industrial Capitalism halts and occasions fierce revolts.

It came very late to Italy; it has taken no strong root in Catholic Ireland; its triumphs have been everywhere the triumphs of the Protestant culture — in Prussianized Germany, in Great Britain, in the United States of America.

The Calvinist has fitted in with it admirably and has indeed actively fostered it.

If we go behind the external phenomena and look at the workings of the mind we find the disagreement between Catholicism and Industrial Capitalism vivid and permanent. There is something irreconcilable between the one and the other.

There is the point of Usury, which I have dealt with elsewhere, there is the all-important point of the Just Price, there is the point of the “Panis Humanus” — man’s daily bread, the right possessed by the human being according to Catholic doctrine to live, and to live decently.

There is the whole scheme of Catholic morals in the matter of justice, and particularly of justice in negotiation. There is even, if you will consider the matter with an active intelligence, underlying the whole affair the great doctrine of Free Will.

For out of the doctrine of Free Will grows the practice of diversity, which is the deadly enemy of mechanical standardization, wherein Industrial Capitalism finds its best opportunity; and out of the doctrine of Free Will grows the revolt of the human spirit against restraint of will by that which has no moral authority to restrain it; and what moral authority has mere money?

Why should I reverence or obey the man who happens to be richer than I am?

And, with that word “authority,” one many bring in that other point, the Catholic doctrine of authority.

For under Industrial Capitalism the command of men does not depend upon some overt political arrangement, as it did in the feudal times of Catholicism or in the older Imperial times of Catholicism, as it does now in the peasant conditions of Catholicism, but simply upon the ridiculous, bastard, and illegitimate power of mere wealth.

For under Industrial Capitalism the power which controls men is the power of arbitrarily depriving them of their livelihood because you have control, through your wealth, of the means of livelihood and they have it not.

Under Industrial Capitalism the proletarian tenant can be deprived of the roof over his head at the caprice or for the purely avaricious motives of a so-called master who is not morally a master at all; who is neither a prince, nor a lord, nor a father, nor anything but a credit in the books of his fellow capitalists, the banking monopolists. In no permanent organized Catholic state of society have you ever had citizens thus at the mercy of mere possessors.

Everything about Industrial Capitalism — its ineptitude, its vulgarity, its crying injustice, its dirt, its proclaimed indifference to morals (making the end of man an accumulation of wealth, and of labor itself an inhuman repetition without interest and without savor) is at war with the Catholic spirit.

Belloc on the Modern Scientific Spirit

All of what is invoked above – the essays on the new paganism, Church and State, capitalism (and also usury) would alone be worth the price of this book – several times over.

These essays will be a warm light for my soul for the rest of my days …

However, in addition to these four, the book contains a further twelve.

The subjects range from Catholic education and anti-Catholicism in English history to the revival of Latin, Anglo-Catholicism and the problem of modern skepticism.

We cannot cover them all – but let us take brief note of two more. There is a major piece on the modern scientific spirit, which is most relevant today in light of the new atheism espoused by men like Richard Dawkins and Christopher Hitchens.

Belloc is taking pains to point out the flaws that compromise this powerful, normative force in post-Christian civilisation. He distinguishes science itself, a noble enterprise, from a spirit that is hardly scientific but rests confidently and unconsciously on plentiful postulates that can never be proven. He observes, all-too-accurately, I think:

The run of modern Scientific writing takes its form of faith for granted and does not even know that it is a faith.

Things like this, of course, are hardly unique in Christian apologetics. What is perhaps more unusual is Belloc’s analysis of the psychology of the modern scientific spirit. It is an analysis that is both charitable and damning, as Belloc begins by commending the fine features of this psychology:

One is accuracy in detail. Another is industry. Another devotion to the research undertaken. Another is candour: an error having been committed, it is always acknowledged in what is called the “Scientific world”; further experiment, modifying what has been hitherto accepted, is not usually boycotted.

Though there is necessarily jealousy among scientists, as there always will be among the members of the same profession, there is more generosity than in most callings.

And the last and by far the finest in this list of the better characteristics in our Scientists is an indifference to wealth, such as you may find, indeed, in most men absorbed in any occupation, but particularly here. There are exceptions, but they are rare.

It is almost a commonplace that the robbers of finance can prey at will on the Scientist, and it is to the honor of the Scientist that it should be a commonplace.

And yet for all these admirable things, Belloc notes the dark side, which seems no less true today than it was ninety years ago.

Unfortunately there are many other less admirable characteristics which very strongly mark the Scientific corporation as a whole. I think it will be of interest to catalog some of these seriatim.

First, I remark a set of characteristics in them exactly corresponding to what the Scientists themselves used to denounce as ‘priestcraft’; what may be called the ‘Mumbo-Jumbo’ group — and Heaven knows it applies a great deal more to the scientists than it ever did to the priests of any false religion.

Part of this is the ‘Superior information’ business: telling the layman that he cannot follow the difficult process by which a result has been arrived at, and that therefore he must take it on trust. There is also something of an hieratic language, but of a very undignified type: litanies of words barbarously compounded from Latin and Greek, sometimes in a mixture of the two with the vernacular. Part of this is no doubt necessary; one must have technical terms, one cannot be forever explaining. …

There is also the Marvel. Here the scientist has a most powerful instrument, the more powerful that it does not pretend to depend — as in the old Pagan priestcraft — upon an irrational process, but upon methods which anyone can use if he will give up his time to them.

The Scientist will be forever showing us that things are not what they seem, expatiating upon the astonishing character of Scientific achievement.

Thus, I read in a book which has sold by scores of thousands under the name of a chief scientific authority in the department of physics, that the hypothetical ‘electron’ is “at once everywhere and nowhere’ — and this nonsense is swallowed whole by people who smile at the mystery of the Trinity …

From this solemn hieratic humbug, comes the habit of speaking of fellow pundits in terms of reverence and awe, calling upon us outsiders to worship them, ascribing to them all manner of rare virtues, and even, when things go wrong, dubbing them “martyrs.”

There is by the way no more absurd example of “Scientific’ Mumbo-Jumbo than this last. A ‘martyr to science’ should properly mean one who bears witness to scientific truth by submitting to suffering rather than recant his conviction.

In this sense, men are indeed martyrs to scientific truth who sufficiently anger the Scientists by pointing out their mistakes. …

But our new priesthood does not use the word ‘martyr” in this sense at all. They apply it to a man who is blown up in the course of a chemical experiment, or who dies of a disease caught in a medical one. And as for ‘the gulf between clergy and laity,’ which was made such a grievance of against real priests; it is nothing to the gulf between the ignorant herd and Scientific Persons.

They show a corporate and almost universal contempt for the man who has not had the leisure to go through all their studies, but who can bring valid criticism to bear on their laughable conclusions; they do not meet his criticism in its own field, they appeal to Status, to their own necessary and unapproachable superiority.

What can be said at this point? I will limit myself to this in passing: that Belloc having written ‘nonsense’ about quantum physics in the 1920s is an understandable, forgivable thing.

Belloc’s real point here is about double standards for science and religion. And here, he is lamentably all-too-correct – for he was a man who was all-too-astute.

This astuteness leads him to probe what lies at the fount of this modern scientific psychology:

Let us ask ourselves how this tone of mind grew up. What influences were at work to create this lamentable Modern Scientific Spirit?

To seek an answer to such a question is of practical utility, for you cannot attempt to remedy an evil until you have understood it, and you cannot understand it until you have some knowledge of its causes.

The causes in this case, being buried in that profound and multiple thing, human character, largely escape us; but some main causes I think we can trace.

First we have the mechanical process which in the case of documentary criticism consists largely in mere counting; and in physics in the mere establishment of regular recurrence.

That the scientific worker should be limited to this tedious and lifeless round is necessary.

He should be pitied for being under that servitude, not envied for it, still less admired for its effects upon him. Subjection to such a mechanical round is in the very nature of his trade.

It is as inevitable to his work as muddiness is inevitable to a hedger and ditcher. If he could take it humbly, and if the man who is perforce occupied in this mechanical life admits his limitations, no harm is done to him or his readers; on the contrary, he is very useful, he is adding to our stock of knowledge.

But if he allows the worst effects of such a life to warp his philosophy the result is ill indeed.

And Belloc then proceeds to an argument as to how this quantitative, mechanical spirit has warped scriptural exegesis – e.g. counting up the number of times items of vocabulary are used to ‘establish’ different authors’ hands in certain books of the Bible, etc.

O Hilaire Belloc, how acutely you witnessed this mechanistic spirit in all walks of life! Beyond Valentin Tomberg, I see so very few, who were as acute as you in realising how sterile this would make our souls …

But let us now sound a note of hope that you have provided for our barren souls, we who live in this world generations after you.

For we who live in this arid, mechanical, soulless system you prophesied so well are so in need of hope …

Hope in the Traditional Catholic Internet

But what?! How could Hilaire Belloc in the 1920s have anything to say that is relevant to the Catholic Internet?!

Bear with me, dear Reader – or as Belloc would say, dear Lector …

Most of this book is about the problem, rather the solution.

But there is one notable exception – an essay Belloc wrote on the fact that English society in his day was singularly lacking in one thing, compared to the Catholic Europe he knew and loved so well:

A Catholic Press … is of very great service and has grown up naturally through the conditions under which Catholics live …

In all countries where the Catholic body is to be found, even where Catholicism is the active religion of the great bulk of the people, there is a Press of this kind …

Such a journal as La Croix, in France, is an example, and there are a host of others …

There is a Catholic Press all over the place in Ireland, and a solid Catholic Press — by which I mean a Press including daily papers and secular papers of all kinds with a Catholic tone – in every other western country except Great Britain. Holland and Prussia have one, as well as Spain, Italy, France, Bavaria, Austria and Poland.

England is the exception even among anti-Catholic nations.

Now this and much of the rest of the essay would appear quite dated – at first. But if we allow for the fact that Belloc is writing more than eighty years ago, is there not still not something all-too-relevant today when Belloc issues the following call?

We need a Press which shall have a general interest; one in which the effect of Catholicism shall be felt without direct intention, as it were, just as in all the Press around us the effect of anti-Catholicism is manifest, although the editors and readers of that Press would be astonished to hear that this was so.

We need a Press in which you may read on any subject of the day – the present controversy on Protection for instance, or the state of affairs in Russia, or a judgment upon fiction, or history, or the stage, which shall give to the reader the opposite implication to anti-Catholicism which he will find in nearly all non-Catholic papers. Until we have such a Press we suffer serious disabilities …

The sanity for which we stand and the solidity of tradition which it is ours to maintain in a dissolving world will not, until we have some such general organ, affect anyone outside our own very restricted body. And in the second place, our own people will, — until we have such an organ, only be able to get their general reading under anti-Catholic direction.

Our people will, in any case, get most of their reading under anti-Catholic direction, for we are citizens of an anti-Catholic society; but had we such a Press as I am here speaking of, the anti-Catholic effect would be corrected.

For instance, in a Catholic Press of this kind European affairs would be seen in their proportion; the reader of it could see international problems as they are and not as the anti-Catholic Press presents them through colored spectacles.

There would be room for plenty of difference on policy and appreciation of other nations, but, at any rate, the reader of such a Press would occasionally hear that there was something to be said for Poland; that the Germans are not identical with the Prussians of Berlin; that there is a Spanish culture of the very highest value to Europe; that it is in very grave peril through an active anti-national and detestable clique which has seized power; and he would learn something of the great religious quarrel in France, which is of the highest political importance to our time.

He would understand how that religious quarrel in France weakened the French at their entry into the war; especially how it weakened them in their failure to negotiate a lasting peace and in their subsequent foreign policy …

Today we get nothing but a sort of conventional anti-Catholic litany, an unceasing stream of abuse and misquotation directed against the Catholic side of Europe.

It is very wearisome, very futile, and in matters of policy dangerously misleading.

We never get Europe presented as it is.

The half dozen major problems of international policy turn upon religious culture, and the most important of them upon the conflict between the Catholic and the anti-Catholic culture in Europe.

Educated men want to hear these things at least mentioned; they want discussion of them to be in terms of reality, and they are not satisfied.

The demand is not met. We get the Prussian case against Poland by the bushel. Whoever hears the Polish case against Prussia?

I have spoken recently of my life in Catholic Europe – and how it led me to see how my own Anglo-American heritage blinkered me.

Today, the Anglosphere is no longer championing Protestant Germany over Catholic Poland etc., but the song remains the same. The lyrics may have changed somewhat to fit the times. But still I hear the same old tune that Belloc did.

The Anglosphere remains severely deprived. Seeing all this, Belloc longs for a daily paper in England, like the ones in France and Ireland, but regards it impossible.

But here is the rub, dear Lector, while an English language Catholic daily is still impossible in England and America – we now have the daily internet.

Today, we can heed what Belloc wrote more than eighty years ago. It may seem dated at first, but truly it is worth trying to peer into Belloc’s astute reflections now.

And thus I offer some more, without much further examination, in the hope they may stimulate the Catholic internet and blogosphere in meritorious ways …

Such a Press would keep general interests in their due proportion; it would not emphasize the horrible or the obscene; it would not prefer tranquillity to justice in the discussion of social affairs.

On sexual matters it would present the old tradition of decency and sound morals; it would present the right apology for property; it would show what authority was and distinguish it from mere force.

Such a review would obviously do good to the non-Catholic world. At present the right view of life is not so much denied as ignored. Men do not come across it. Even in the specialized world of apologetics we Catholic writers stand in the rather ridiculous position of perpetually preaching to the converted …

With such a review we should teach, and we should teach a society which is not only insufficiently taught but is growing less and less taught every day – and an expansion of learning is one of the prime necessities of our time.

Perhaps the best effect of all which such a journal would have, would be its effect upon the Catholic body itself.

It would provide an arena for controversy, it would strengthen the confidence of Catholics, it would instruct them, it would provide them with material, and it would be an introduction of it to the non-Catholic body outside.

So much more might be said, but I cannot tease it out now. I only hope my fellow bloggers may stumble upon this and thereby profit. We have only scope now for a little conclusion.

Belloc on the Fall of Christendom

In summing up this book, let me turn once more to Valentin Tomberg on the slow death of the West:

The Virgin is not only the source of creative élan, but also of spiritual longevity. This is why the West, in turning away more and more from the Virgin, is growing old, i.e. it is distancing itself from the rejuvenating source of longevity. Each revolution which has taken place in the West —that of the Reformation, the French revolution, the scientific revolution, the delirium of nationalism, the communist revolution —has advanced the process of aging in the West, because each has signified a further distancing from the principle of the Virgin.

In other words. Our Lady is Our Lady, and is not to be replaced with impunity either by the ‘goddess reason’, or by the ‘goddess biological evolution’, or by the ‘goddess economy’.

The adulation of all these “goddesses” bears witness to the unfaithfulness of so-called ‘Christian’ mankind; it very much resembles the sort of spiritual adultery which the Biblical prophets gave so much utterance to.

It is, still more, a sin against one of the commandments of faithfulness to the principle of non-fallen Nature, the Virgin Mother, namely the commandment: Thou shalt not commit adultery.

Belloc’s book of Essays is very much about the sins of adultery. It is about ‘the unfaithfulness of so-called ‘Christian’ mankind’.

It is about unbridled capitalism as Christians trying to sleep with the ‘goddess economy’.

It is about Christians trying to accept modernity by sleeping with the ‘goddess reason’ and the ‘goddess biological evolution’.

It is about the fall of Christendom.

It is about why the only hope for the Western is the Mystical Body of Christ and therefore the need for Catholic restoration.

The challenge was arduous, even in Belloc’s day. Much of the book makes for somber, sobering reading.

And for all of these reasons – as well as Hilaire Belloc’s pierced heart and passionate spirit – I can hardly recommend it highly enough to those who care about the same things I do.

Foreword for Monarchy by Roger Buck

Buying Books at Amazon Through These Links Gives Us a Commission. This Supports Our Apostolate. Thank You if You Can Help Us Like This!

Comments

comments are currently closed

7 responses to “Essays of a Catholic: A Fine Introduction to Hilaire Belloc (Review)”

[…] « Essays of a Catholic: A Fine Introduction to Hilaire Belloc (Review) Christendom and the Dictatorship of Relativism » […]

[…] [Extract from Essays of a Catholic in 1931, with italics added and some liberties in punctuation and paragraphs to make it more easily assimilable from a computer screen. I also have an in-depth review of those Essays here, where more is quoted from and commented on.] […]

Great article and introduction to Belloc. Excellent website!

A ridiculously belated thank you, Mark!

Actually, Belloc might be considered to agree with Ratzinger a bit.

If he considered the schism as a criminal act, he nevertheless considered the religion of the Orthodox as substantially identic to the Catholic faith.

HGL – thank you. Belloc is far more nuanced than many people think when you read him closely. All that French passion of his – I think the genteel Anglo-Saxon mind often fails to get him …

Very good review. 🙂

“Today, they are choosing – whether consciously or unconsciously – that which marginalises Christ and His Church.”

Let’s not be too polite: they choose Antichrist… Satan. The full severity of the apostasy is not understood from these quotations. When Christianity is rejected by the West, the consequence is not just a regression to pagan barbarity, the end-result is darker by far. The old paganism was grey. The final consequence of this apostasy will be black. Satanism rather than mere paganism. The darkness of rejecting Christianity after having received it is blacker than the ignorance of not yet having encountered it. But it is a necessary part of separating the sheep from the goats before the end of the age. Christ came with a sword. There is more light after Christ, and it increases, deepens as the Second Coming is approaching. This will finally make the darkness appear more unmasked and exposed than it was in the old pagan times.