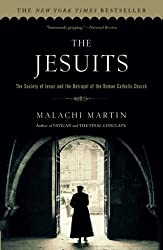

This is a book about war – outright warfare – in the Church.

Like most of the late Father Malachi Martin’s works, it is about the war in the Church between conservatives and progressives, so-called.

And like most of Father Martin’s works, it is about war not simply in this world – but the world beyond this world, as well.

Because, although tremendously learned and scholarly, Malachi Martin does not succumb to the temptations of modern academia: he does not shy away from speaking about either the supernatural or the preternatural.

In this volume, the late Father Martin – an ex-Jesuit himself – brings all of his acumen and years of firsthand experience to bear on the very special problem, as it manifests in his former order.

For him to do so, would to be make concessions to the precise kind of worldly, materialistic mentality which he argues – very powerfully – has now betrayed the Catholic Church …

As the author says starkly in the very first sentence of the book:

A state of war exists between the papacy and the Religious Order of the Jesuits – the Society of Jesus to give the order its official name.

The subtitle of the book is equally uncompromising: The Society of Jesus and the Betrayal of the Roman Catholic Church.

The picture here is dark, very dark.

I recall how years ago I first came to Malachi Martin. I was concerned then by the dark, seemingly too polarised, too black and white image he painted of contemporary Catholicism.

I was a more liberal Catholic then – and I was trying to read a broad spectrum from left to right.

Thus on the left, I read things like John Cornwell’s outright attacks on the Church. I read Richard McBrien’s more subtle and arguably much more insidious attacks …

And I read Father Martin on the right.

I was bewildered. Both sides had genuine concerns, it seemed to me, at the time …

The years have passed. I regret to say that these years have confirmed for me over and over again, the dark picture that Father Martin was painting, which exists on so many fronts at once in the Church today.

After years of pondering Martin´s writing, I can now declare unequivocally: This is an important book.

It speaks very deeply to the crisis which exists in the Church as a whole – as do other volumes from the same author, including Windswept House, which I have reviewed here).

However here the setting is restricted to the Jesuit arena of course and how little by little, the nature and purpose of the order was completely transformed by modernism.

That is to say, it speaks of a complete reversal of what Jesuitism has been.

Here we can do no better, I think, than to listen to the author in his own words, as he sums up what the Jesuits were in the past and what they have become:

Classical Jesuitism, based on the spiritual teaching of Ignatius, saw the Jesuit mission in very clear outline.

There was a perpetual state of war on earth between Christ and Lucifer. Those who fought on Christ’s side, the truly choice fighters, served the Roman Pontiff diligently, were at his complete disposal, were ‘Pope’s Men.’

The ‘Kingdom’ being fought over was the Heaven of God’s glory. The enemy, the archenemy, the only enemy, was Lucifer. The weapons Jesuits used were supernatural: the Sacraments, preaching, writing, suffering. The objective was spiritual, supernatural, and otherworldly …

The renewed Jesuit mission debased this Ignatian ideal of the Jesuits. The ‘Kingdom’ being fought over was the ‘Kingdom’ everyone fights over and always has: material well-being.

The enemy was now economic, political, and social: the secular system called democratic and economic capitalism.

The objective was material: to uproot poverty and injustice, which were caused by capitalism, and the betterment of the millions who suffered want and injustice from that capitalism.

The weapons to be used now were those of social agitation, labor relations, sociopolitical movements, government offices …

What Martin sums up here in precis, he then unfolds in erudite detail throughout the book – including the kind of detail only an insider, that is to say a former Jesuit himself would know.

Added to this picture of the transformed spirit of Jesuitism, is also – as we noted before – a dark picture of how that spirit has declared covert war on the Papacy …

As disturbing as all this is, it forms required reading I think, for anyone who genuinely wants to get to grips with the crisis in the Church today.

Yet as important as all the above is, the book has had yet another very valuable function for me.

For in the course of a 500 hundred volume, largely devoted to the present day crisis and its origins – there is a 150 page exception.

One might even say these 150 pages or so constitutes a book within a book – a little book that could stand on its own, if need be.

For in this immensely valuable section, Father Martin tells the story of St Ignatius of Loyola, and the story of his distinct spirituality and the Society he created.

Martin is an exciting, engaging writer. Really these crisp, clear 150 pages about the history of the Jesuits render a real service, just in themselves.

Again, I think I can do no better here, than to give a flavour of this subsection of the book by quoting Father Martin at length.

Here he is he speaking of St Ignatius Loyola himself, although he calls him by the more intimate name Iñigo, which was the name the Saint was baptised under before he romanised it to Ignatius. And he is invoking the Saint’s origins as a former soldier for the Spanish monarchy and the crisis that transformed him a soldier for the king to soldier of the Church at the very moment of the Reformation:

Out of this crucible of trial, self-examination, and anguished yearning for peace and light there emerged in Iñigo de Loyola that balance of spirit and matter, of mind and body, of mystical contemplation and pragmatic action that has ever since been recognized as typically and specifically “Ignatian,” as distinct from the spirituality of, say, St. Benedict or St. Dominic or St. John of the Cross and St. Teresa of Avila.

Iñigo desired nothing more ardently then to meet the Risen Christ in person in his glorified body, and to venerate each of Christ’s wounds-in his hands, his feet, his side, to kiss those wounds and to adore them, to cover them with his love and adoration expressed by his lips and his eyes and his hands.

He had discovered that secret of Christian mysticism that makes it totally different from the disembodied-almost anti-body-mysticism of the Buddhist; a secret which in our time has eluded the minds and experience of far more illustrious men, humanly speaking, such as Aldous Huxley, Teilhard de Chardin, and Thomas Merton.

Automatically, the promise of Christ was fulfilled: “Who sees me, sees the Father.” Through the very humanity of Christ, Inigo was introduced into the bodiless, eternal being of the Trinity apparently ascending, like Paul of Tarsus in his out-of-body ecstasy, to the “Third Heaven,” to participate in the most hidden secrets of divinity for which human language has no words.

God the Father, the Son, the Holy Spirit, as Three and as One, admitted Iñigo to an intimacy that few mortals every approach while alive on this earth.

This characteristic of genuine Christian piety – ascension to a bodiless spirit, God, through the humanity of a real man, Jesus is a stumbling block for the non-Christian mind. But it is the touchstone by which you can find out what is authentically Christian or non-Christian in the turmoil of religion today.

When he had gone through all this travail of spirit and achieved the balance that would always mark the Ignatian way-balance between spirit and matter, between contemplation of the divine mysteries and implementation of their meaning in concrete actions-he had also finished putting together his book of Spiritual Exercises.

He was ready now to test in action his ideals of service in the Kingdom. His basic categories of judgment remained from the earlier part of his life: love of the leader, service in the Kingdom, war against the Enemy across the recently opened-out battlefield of the world, the absolute necessity of total education, love expressed in unconditional service.

But in his conversion, these ancient categories of his were filled out with totally different ideals and dimensions.

Iñigo himself described minutely how he now saw everything.

The Enemy was that “murderer from the beginning,” Lucifer, “the chief of all the enemies [who] summons innumerable demons and scatters them throughout the whole world to bind men with chains [of sin].”

The Kingdom was “the whole surface of the earth inhabited by so many different peoples…. The Three Divine Persons [of the Trinity] look down upon the whole expanse or circuit of the earth filled with human beings … some white … some black … some at peace … some at war, some weeping, some laughing, some well, some sick, some coming into the world, some dying….”

The summons of Their Most Catholic Majesties he heard no longer.

It was Christ, the Supreme Leader, who was calling him now, and … how much more worthy of consideration is Christ Our Lord, the Eternal King, before whom is assembled the whole world.

The dominating question for Iñigo now concerned loving service of his new leader, Christ. How could he serve? And where?

Alone? If not, then with whom? How was he to know what service God required of him?

In 1523, in a quest for answers, he made a pilgrimage to Jerusalem. When he returned, he had made up his mind: He decided that the first step would be to become a priest. For this, he needed to study.

He began his studies in Spain, at the age of thirty-three or thirty four; but in 1527 he made his way to the largest and most renowned university of his day, in Paris …

By 1535, Iñigo’s vision of the world around him was quite defined and definitive: There was, universally, a war in progress.

It was not to be confounded with local wars- as, say, the Turks who under Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent had reached the walls of Belgrade in 1521, or the Spanish imperial army that had sacked Rome and the Vatican in 1527.

It was not even the war being waged against the Lutherans, the Calvinists, and others who had revolted against the authority and teaching of the Roman Pope.

Nor was it the war being waged by a few zealous and compassionate souls against the endemic poverty, disease, and injustice that characterized the social conditions of the masses of people throughout Europe of his day.

The war Iñigo saw was the war against Lucifer, chief of the fallen angels, who roamed the human environment seeking to destroy-whether by the homicide of war, by the destruction of religious culture, or by the degradation of poverty, injustice, and suffering-the image of God and the grace of Christ in the souls of men and women everywhere.

As Lucifer’s war against Christ and his grace and salvation was universal, so the war against Lucifer and his followers had to be correspondingly universal.

Iñigo, therefore, had a basic operating principle: Quo universalius, eo divinius. The more universal your operation is, the more divine it is.”

From such beginnings, the late Father Martin will then trace the entire history of the Jesuits.

And of particular relevance to this website, he will also tell the story of why it was that Devotion to the Sacred Heart of Jesus was once the premiere devotion of the Jesuits.

Once, but no longer …

In sum, here is a tremendously erudite and penetrating telling of the story of Jesuitism, from its beginning to what the author starkly calls its betrayal: the betrayal of its founder’s intentions, the betrayal of the Papacy in the present epoch under Paul VI and Bl. John Paul II …

This author and book have rendered great value for me—on numerous fronts at once.

Foreword for Monarchy by Roger Buck

Buying Books at Amazon Through These Links Gives Us a Commission. This Supports Our Apostolate. Thank You if You Can Help Us Like This!

Comments

comments are currently closed

5 responses to “The Jesuits – Malachi Martin (Review)”

[…] dark. I recall how years ago I first came to Malachi Martin. … View full post on roman catholic – Google Blog Search Tagged with: book • Jesuits • Malachi • Martin • Review If you […]

[…] I have not gained permission for the following lengthy quote from Malachi Martin. However I recently reviewed his book The Jesuits and as something of an adjunct to that review I offer this material from […]

[…] As the former Jesuit Malachi Martin detailed in his study of The Jesuits (reviewed here), this tendency is now full blown in modern Jesuitism. […]

[…] Colombiere provided the bridge by which her vision of the Sacred Heart of Jesus became central to Jesuitism … (The interested reader may find much more by following the links I have given as well as […]

[…] Malachi Martin powerfully sums this up, in his book, The Jesuits: […]

An amazing book that tells in detail what happened and is happening to our church. Now with a deluded Jesuit as our Pope even more relevant.