Introduction (by Roger Buck)

We are delighted that Charles A. Coulombe, the Catholic historian – and Papal Knight, knighted by St. John Paul II! – has granted us permission to feature the following lengthy article here at this site.

Long-time readers will know how much I enjoy Charles’ work. I find it fascinating, incisive and intellectually stimulating, filled, as it is, with an encyclopaedic knowledge of history (which moreover is liberated from the secular, Freudian reductionism that thoroughly permeates most academic texts today).

Charles’ great understanding of history also renders him something else: a healthy sense for the tragedy of modernity. Few Catholic hearts can be as pierced today, as his is pierced: realising far more than we, everything that has been lost …

In this piece on Europe, both these aspects of Charles’ work feature side by side: the horror of the soulless, sterile, abstract European Union and a haunting evocation of Christendom, of Abendland.

Some of what Charles writes here will trouble certain folk. Indeed, it troubled me in my own highly liberal past. Even today, I do not necessarily agree with every statement. However, this piece helped me and I pray it can help many others. Moreover, I salute Charles’s considerable bravery (something I imagine will have brought him real suffering over the years). It is hardly easy to stand against the entire tide of modernity like THIS!

Now, I just described Charles’ work as mentally stimulating. Perhaps, however, its greatest value is to stimulate the heart and soul even more.

For beyond the purely mental level of facts and concepts – as well as arguments and counter-arguments this piece may produce – I find something numinous, magical and – to repeat my epithet above, for none other will do – haunting in his evocation of the lost Christian Emperor and the lost Christian Empire.

Put simply, it feeds my soul in a way that my mind can never fully understand.

Thus, it is offered here in the same spirit, dear Reader – something that may stimulate and feed you in mind, heart and soul.

Now, as Charles himself writes below:

Eurosceptics, Pan Europeans, Catholic activists, neo-Imperialists – none of these need agree on all points at this stage. What they must do is talk with each other …

We offer this in this same spirit. Let us talk to one another. Let us listen to one another. Charles will perhaps say things that will confound or upset. But I urge you to keep listening. I was once confounded by Charles. But I kept listening. And how very glad I am I did!

Here I also want to draw a link to Valentin Tomberg’s Catholic masterpiece, Meditations on the Tarot. Charles appreciates Tomberg’s work and includes here a mysterious passage from Tomberg’s letter on the Emperor (or the Fourth Arcanum of the Tarot).

This is to suggest that many striking parallels exist between Tomberg’s Christian political thinking and that of Charles. Both men regard the disastrous course of modernity in recent centuries in a remarkably similar way.

Indeed, a passage from Tomberg’s legal-political theses strikes me as particularly appropriate at this juncture:

The French Revolution was but a stepping stone – a stepping stone that demonstrated with alarming clarity the great trend of revolutions which began with humanism in the Fourteenth Century, then resulted via the Reformation in the Enlightenment of the Eighteenth Century, which in turn, took “fleshly” form in the revolution of 1789.

From there it advanced via 1830 and 1848 to the international community of 1871 [when the Third French Republic arose, among other things – RB] – and to the Russian revolutions in 1905, February 1917 and October 1917.

The beginning of the revolutionary development is harmless humanism, the swooning over laical [i.e. from the French laicité and meaning secular – RB] culture; and it ends with Black and Red Bolshevism – as the final result of the destruction of the great temple of piety, in which and from which the soul of the occident draws its life-force.

The joy of thinking and researching without God in laical humanism led to the first push in the direction towards further “emancipations”, i.e. the severing of the bonds of reverence: reverence for the Church´s tradition, including her saints and sages; reverence for the tradition of chivalry, including its reverence for women and the sancity of word and honour, finally reverence for the human being itself, with its right to life, liberty and property.

One started thinking without God and one ended up with life without God, the push to liberate oneself from one bond (research liberated from religion) led ultimately to the liberation from all bonds.

Thus was created a human without reverence, the psychological Bolshevik … [Tomberg’s emphasis in bold, mine in italics]”

I cannot but imagine that Charles feels precisely the same!

Moreover, Charles most certainly also agrees with the core of Tomberg’s political thinking: humanity is in ‘mortal peril’ – as Tomberg once put it – if we continue our present cultural course of life, thinking – and politics! – without God.

Thus, Valentin Tomberg and Charles Coulombe both call – each in their own separate ways – for nothing less than reversing the Enlightenment demolition of Christendom and restoring the sacred relationship whereby the State serves the Church, as the body does the soul.

Alas, we cannot say much more than this now and most of Tomberg’s political thinking is not easily available in English. However I have a label, Catholic Jurisprudence (here) which features articles pertaining to Tomberg’s legal-political philosophy. (Moreover, my own publisher Angelico Press is interested in bringing his theses out. Contact them if you are interested!)

Without further ado, here is Charles A. Coulombe’s call to a very different future for Europe than that envisioned by the likes of Merkel, Hollande, Cameron and, here in Ireland where I write, Enda Kenny! (Although because the piece is some years old, Charles refers to people like Chirac, Blair and Ireland’s Bertie Ahern. The names may have changed – but not the mentality!)

Possibly, dear Reader, you will object to certain notions here. (Most Westerners in our ‘enlightened’ society will and do!) But I hope you may also agree with me that Charles Coulombe understands what is truly important far better than any of Europe’s sclerotic elites!—Roger Buck

From Charles A. Coulombe:

I am a European. This may sound rather strange, given that I was born in New York, have lived most of my life in Los Angeles, and will be buried in my family plot in Massachusetts. The first Coulombes to come to the New World arrived in the 17th century, and my immediate ancestors have served in the armed forces of the United States in every conflict this country has been involved in since 1900. I myself have so served, and once upon a time swore to defend the U.S. constitution from “all enemies, foreign and domestic.”

Nevertheless, I am indeed a European. The fact is that, save for some Indian blood (visible in my Coulombe cousins, though not in myself), my ancestry hails from the mother continent. Mixed — French, Austrian, English, Russian, Scots, Irish, and various others — to be sure, but nevertheless all European.

None of the languages I speak, however poorly — Canadian French, Yankee English, a fractured Viennese, and Los Angeles Mexican street Spanish — can be considered indigenous to the Americas, and as a result, all of the arts to enjoyed in the languages I understand have European origins — from Shakespeare to Piaf.

In the State of California, where I reside, although the laws covering land, water, and minerals point up our origins as a colony of His Most Catholic Majesty of Spain, the rest of our governance, with its panoply of governor, legislature, judiciary, counties, sheriffs, mayors, coroners and on and on, show the English origins of the better part of our law and institutions.

Above all, I belong to a religion centered in Rome, whose current head said shortly after his accession, “all Catholics are in some way Romans.” It is unlikely that he was referring either to Rome, New York, or Rome, Texas.

Of course, I am not alone in this position. It is true of the larger proportion of my fellow Americans ethnically, and virtually all of us culturally. It is especially true of the Blacks in this country, who have no real, identifiable, ties to Africa (despite all the hype), except mere genetics. If anything, they are, save the Indians, the most completely American cultural element in the population. But that too makes them Europeans.

The truth is, pace the Anti-Colonial League, that we are the most successful of colonies, having succeeded so tremendously that we have dominated all our former metropoles, and their neighbours. Moreover, most of us have forgotten our origins, and unconsciously think of ourselves as autogenetic.

But on a deeper level still, we know that it is not true. Old Europe still keeps a hold on our imaginations, no matter how much we may try to deny it. Moreover, the fact remains that none of us without tribal ancestry can stand on a bit of land in this country and say, “my people were here a thousand years ago.” The equally unconscious ability of Europeans to do precisely that (and of those few Americans who visit to do likewise) quietly influences the relationship between the two sides of the Atlantic — Canadians, of course, are somewhat more aware of their origins, which gives them a separate mental universe entirely.

From Christendom Our Fathers Came, from Abendland …

For my own part, a large segment of my work as a writer has been to imply the truth: that we Americans are Europeans separated by time and space from our origins. But as with any colonial, it is not the Europe of Tony Blair, Bertie Ahern, Jacques Chirac, and rest of the “generation of ‘68” gone to seed that I have in mind.

There is a reason why the 17th and 18th centuries can still be heard in the French, English, and Spanish spoken in various remote spots in the Americas. It is because we were settled by a different Europe.

The continent that produced our ancestors was the Europe of Dryden, Cervantes, and Moliere — the realm of chivalry and guilds, shrines and legends, for all that (in the northern half, anyway) this was collapsing at a more or less speedy rate. In a word, it was from Christendom that our fathers came, from Abendland.

Echoes of this can be found in the more profound religiosity that characterizes most of the Western Hemisphere — even if much of that religiosity is Calvinism or sects still more bizarre.

It has only been since the ‘60s that our elites have become more or less atheistic, and determined to impose their creeds upon the rest of us (a phenomenon to which neither Quebec or Latin America have been immune, although in the latter case it is still somewhat moderated).

In any case, the malaise that has infected Europe since 1789, and has become more or less triumphant since 1945 and especially 1968, has not gone nearly as far here.

In Europe herself, by way of contrast, American religious attitudes are well-nigh incomprehensible; public displays of religious ceremonial are quite common in Europe (although her current leaders do try to suppress or limit them when possible) to a degree unheard of in the United States; yet the personal faith that is a sine qua non in a politician here is considered rather strange on the other side of the ocean. Marriage and birth statistics reveal that such personal faith is also increasingly rare among the European citizenry at large (a lack, however, noticeably absent in her growing Muslim population).

The altar was one of the two foundations upon which Europe rested: the other was the throne. Of course, since 1776, we have done our best on this side of the water to minimise its contributions to our nationhood; Latin Americans have been doing so since the 1820s, and Canadian politicians and media folk got into the act in the 1960s.

Yet, as earlier mentioned, all of our institutions come to us from Europe — but from a Royal Europe. The same anti-monarchical slant infected Europe in 1789, and received heavy boosts in 1918 and 1945. But European republics still house the dreary old politicians they call presidents in the royal palaces, surround them with more or less cut-rate royal pageantry (guards, households, and orders of knighthood), and pretend that somehow the whole charade has something to with “rule by the people” — as though the general mass of the people were able to live as well as the politicians that batten off them! Much the same is true in Latin America, where current chiefs of state continue to use many of the appurtenances of the long-vanished viceroys.

For all of the differences between old Europe and her children, however, there can be no doubt that, despite the end of colonialism and the attempts at self-assertion of local politicians in such nations as Australia, Europe really extends from San Francisco to Valdivostok, and from North Cape to Cape Town and Buenos Aires.

Like it or not, we are stuck with each other. But culturally and religiously, the health of the periphery still depends upon that of the Mother Continent. Europe’s health, over here, is frequently spoken of in terms of the European Union. But just what is that Union, and how true is it to the European soul, of which Hilaire Belloc once famously remarked that, “the Faith is Europe, and Europe is the Faith!”

One must say, given the disastrous course of European history in the 20th century, that the origins of the EU were promising enough. Solid Christians like Jean Monnet, Paul-Henri Spaak, Robert Schuman, Konrad Adenauer, and Alcide de Gasperi hoped to pull out of the ruins of their countries a new Europe — rooted deeply in the religion and best traditions of her past, but freed of the national hatreds and social conflicts that had spilled so much of the best of her blood from 1914 to 1945.

It was a noble dream, reflected in such efforts as the Karlspreis, the annual award by the city fathers of Aachen, Charlemagne’s Aix-la-Chapelle, to the individual who, in their opinion, had best demonstrated the “European idea” that year.

In time, the ACP (Atlantic-Caribbean-Pacific) scheme was intended to allow the former imperial masters to aid their one-time colonies in a way consonant with those nations’ self-respect. Moreover, European unity would allow Europe to play an effective role in world affairs, independent of both the United States and the Soviet Union. Yet at the same time, the principle of “subsidiarity” would allow towns, counties, and provinces (or their local equivalent) far more freedom to run their own affairs. Successive Popes seconded this goal — and came to prefer it to the older vision enunciated by such as Salazar, Franco, and any number of Latin American rulers.

Alas, the reality was to be far different from what either Pontiffs or founding politicians had hoped. For what we are faced with in the European Union of 2006 is quite another thing, entirely. Far from the sort of Europe envisaged by the Founders, the EU is, to begin with, ever more anti-Christian, as the abortive Constitution’s preamble and the Buttiglione case point up.

Non-marital unions, contraception, abortion, euthanasia — anything calculated to worsen Europe’s already plummeting demographics — are encouraged at every turn by the EU. Instead of subsidiarity, local farmers, artisans, and regular folk throughout the Union find themselves ever more strangled by the Brussels bureaucracy — what seems to be emerging is a personally oppressive superstate upon a foundation of equally annoying national bureaucracies.

Perhaps making up for this has been the EU’s ineffectiveness in foreign affairs: the ACP idea is being abandoned, having done little to ameliorate Third World poverty and less to address bad governance there. Bosnia and Kossovo pointed up the New Europe’s inability to address even nearby conflicts effectively. Needless to say, the U.S. took little notice of Europe when dealing with Iraq — alas, perhaps, to no one’s ultimate advantage. The only thing more pitiful than the awarding of the Karlspreis to Tony Blair in 1999 was Bill Clinton’s reception of it the following year.

As a result, despite the best efforts of a well-healed PR machine, and the views of most European political parties, the EU has yet to win the affection of the common man in Europe. Instead, most folk respond with derision. Yet despite polls and plebiscites, the thing appears to be on its way to commanding ever-greater power over a supine continent. Since the 1980s, a common explanation was to blame the next country over for the EU. British blamed the French, Frenchmen blamed the Germans, Germans blamed the Italians, and so forth. In recent years, this sort of round robin of finger-pointing has subsided.

The Elites of Europe

That is probably just as well. Because the plain truth is that the EU’s failings are not to be laid at the door of any single nationality.

Rather, responsibility for them rests communally with the greater part of the dominant elites in each country of Europe, with such as the earlier cited Blair and Ahern, Belgium’s Guy Verhofstadt, Spain’s Jose Luis Rodriguez Zapatero (he masculinised it from “Zapatera;” in light of his support of homosexual marriage, he need not have bothered), and the now cashiered French and German premiers Jospin and Schroeder.

What all of these worthies and their numerous hangers-on, concubines, and flunkies in government, the judiciary, and media have in common is a shared vision.

Products of the 1960s, they simply hate their respective countries, at least as they inherited them.

Naturally, this hatred does not extend to the organs of power, ultimately the gift in most European countries of Bonaparte and such unconscious successors as Bismarck and Cavour, but rather is aimed at the countries themselves — at whatever gave each their own identity.

In all cases, this includes not merely Christianity, but its affect on society and culture; on traditional mores in the family and in the arts.

To make all things anew after their own image was their desire in the 60s, and it remains so today.

Yet each of these nations is a building block in what had been the very real but difficult to define entity called “Europe,” nee Christendom.

Just as, in their hands, their respective countries have begun to morph into something very different to what they had been, so too with the European Union. Nothing is sacred to these folk! Hunting and the House of Lords must go in Great Britain, indissoluble marriage in Ireland, school crucifixes in Belgium and Spain, and strange and unusual means of producing goods in every rural hamlet on the continent, and smoking everywhere (were public health really a concern, these mandarins might turn their attention to limiting such things as the behaviours which spread AIDS).

Behind these lie greater alterations — the self-same all-important demography-busting marriage, life, and family issues earlier referred to.

Is There a Viable Alternative to the EU?

Disastrous as these measure would doubtless be in the long-run, their practical harm is multiplied by the fact that they are all the rulers of Europe have to throw back at militant Islam — managing at once to convince the Muslims of their own moral supremacy, and to limit the ability of Europe to resist. The problem is that the EU has been recast in the leadership’s own image.

All of which having been said, we need to look and see if there is a viable alternative to what is on offer. I once told a German friend of mine (as it happened, in Aachen, outside of Charlemagne’s resting place in the cathedral there), that I was not “opposed to the union of Europe, but to this union of Europe!” He responded, “no, Charles, you are really opposed to the union of this Europe.”

He was right, but is there another Europe to choose? Indeed there is. The noted French Royalist, Charles Maurras, coined the notion of France being divided into two: the pays reel, the real France, Catholic and Royalist; and the pays legal, the legal France, anti-clerical and republican.

Georges Bernanos wrote of life in the former France in his brilliant work Nous Autres Francais — “We Other French.” Perhaps inspired by Bernanos, Phillippe de Villiers called his quondam organisation Nous Autres Europeens. It is the “Other Europe,” the Europe that drew its origin from Rome and Jerusalem that we must look at, rather than the one that is rooted in Brussels (much as I personally love that pleasant city!).

Two centuries ago, faced with the similar problem posed by the new Europe then a-borning, Romantic writer Friederich von Hardenberg (better known as Novalis) penned his best known essay, Christendom or Europe? Its opening paragraph was a battle cry, a challenge thrown down to everything that had happened to Europe since the Reformation:

There once were beautiful, splendid times when Europe was a Christian land, when one Christendom dwelt in this continent, shaped by human hand; one great common interest bound together the most distant provinces of this broad religious empire. Although he did not have extensive secular possessions, one supreme ruler guided and united the great political powers. A numerous guild which everyone could join ranked immediately below the ruler and carried out his wishes, eagerly striving to secure his beneficent might. Each member of this society was honoured on all sides, and whenever the common people sought from him consolation or help, protection or advice, being glad in exchange to provide richly for his diverse needs, each also found protection, esteem, and a hearing from the more mighty ones, while all cared for these chosen men, who were armed with wondrous powers like children of heaven, and whose presence and favour spread many blessings. Childlike trust bound people to their pronouncements. How cheerfully each could accomplish his earthly tasks, since by virtue of these holy people a safe future was prepared for him, and every false step was forgiven by them, and every discoloured mark in his life wiped away and made clear. They were the experienced helmsmen on the great unknown sea, under whose protection all storms could be made light of, and one could be truly confident of a safe arrival and landing on a shore that was truly a fatherland.

This was high-flown Romanticism, to be sure, but not without some basis in historical fact, unlike the visions of the ruling revolutionaries of his day—or ours, for that matter. Certainly Novalis had uncovered the ideal of Medieval society in this passage, if not always its reality. One shudders to think of what the idealism of our current masters, with its glorification of perversion, conformity, and death, would look like, if reduced to writing.

At any rate, the Medieval Christendom of which Novalis wrote so glowingly was not, like modern Europe, a patchwork of more or less stable nation-states, but rather a crazy quilt of minor fiefdoms, principalities, duchies, free cities, ecclesiastical lordships, and strange local groupings not easily described (like the first three forest cantons of Switzerland or Holstein’s Dithmarschen). These in turn were grouped together, for the most part, into various kingdoms — although some of the lesser entities split their allegiance between two or more kings. The monarchs of these countries were sometimes elected, but usually hereditary.

But they were not heads of state in the modern understanding of the term, because the countries they presided over were not states, as we know them now. Lacking secret police or internal revenue services, they had none of the appurtenances of governance we would recognise. Indeed, to our eyes, these countries would have been mere bundles of anarchy.

This is because our ancestors lived in a very different mental universe to ours. Allegiance meant much more than merely being draughted or taxed. Although the King may not have had the ability through his guards to impose his will much beyond his palaces, his subjects loyally upheld the local equivalent of “the King’s Peace.” Did a desperado “play the robber on the King’s Highway?” The neighbours would send up the hue and cry, hunt him down, and kill him in the name of the King — and the consider the “King’s Peace” restored. The nation, to our way of thinking, was a mutually imagined illusion.

But it was certainly real to them, in the sense of Platonic realism. Key to understanding how the mediæval kingdom worked is to realise the difference between power and authority: the former is the ability to make things happen, the latter the right to say how that power should be used.

In Medieval times, power was diffuse, the lords, churchmen, commoners, guilds and so on all claiming their share. Authority however was in the hands of the King. A good King was like an orchestra leader. But under a bad King, (apart from annoyances meted out to his immediate companions) the result was not dictatorship in the modern fashion, but anarchy. When such times occurred, locals would often group together to “keep the peace,” forming a confraternity for that purpose. These bodies often served as local police and militia — such as the famous Santa Hermandades of Spain.

As a side note, it is fair to say that Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II probably has little more power than did her pre-Tudor ancestors (as much the founders of the modern state as anyone — like Louis XIV — else). But because, in our day, power is concentrated in the hands of the elite, while authority is scattered amongst a more or less oblivious electorate, her position looks much less impressive. Such is the modern state.

Binding all of these kingdoms and so on together were several institutions, first of which was the Church, with her several networks of dioceses and religious orders; she in turn gave her blessing to the complementary circuits of guilds and universities. Some of the same benediction touched Chivalry, the “corporation,” as it were of knighthood; this would come in time to include the great military orders, who partook of both the Church and Chivalry.

The Sanctum Imperium

But in, with, and under all of these was the idea of the “Holy Empire,” Roman in the West, Byzantine in the East. We really need to take a close and somewhat detailed look at this Imperial idea, because it provides the great alternative to the notion of the European Union.

Despite many future conflicts between the Imperial and Papal powers, there was an underlying unity between the two which was unbreakable. This is admirably summed up by James, Viscount Bryce, in The Holy Roman Empire (pp.102-105):

The realistic philosophy, and the needs of a time when the only notion of civil or religious order was submission to authority, required the World State to be a monarchy: tradition, as well as the continued existence of a part of the ancient institutions, gave the monarch the name of Roman Emperor.

A king could not be universal sovereign, for there were many kings: the Emperor must be universal, for there had never been but one Emperor; he had in older and brighter days been the actual lord of the civilised world; the seat of his power was placed beside that of the spiritual autocrat of Christendom.

His functions will be seen most clearly if we deduce them from the leading principle of mediaeval mythology, the exact correspondence of earth and heaven.

As God, in the midst of the celestial hierarchy, rules blessed spirits in Paradise, so the Pope, His vicar; raised above priests, bishops, metropolitans, reigns over the souls of mortal men below.

But as God is Lord of earth as well as heaven, so must he (the Imperator coelestis) be represented by a second earthly viceroy, the Emperor (Imperator terrenus), whose authority shall be of and for this present life.

And as in this present world the soul cannot act save through the body, while yet the body is no more than an instrument and means for the soul’s manifestation, so there must be a rule and care of men ‘s bodies as well as their souls, yet subordinated always to the well-being of that element which is the purer and more enduring.

It is under the emblem of soul and body that the relation of the papal and imperial power is presented to us through out the Middle Ages. The Pope, as God’s vicar in matters spiritual, is to lead men to eternal life; the Emperor; as vicar in matters temporal, must so control them in their dealings with one another that they are able to pursue undisturbed the spiritual life, and thereby attain the same supreme and common end of everlasting happiness.

In view of this object his chief duty is to maintain peace in the world, while towards the Church his position is that of Advocate or Patron, a title borrowed from the practice adopted by churches and monasteries choosing some powerful baron to protect their lands and lead their tenants in war.

The functions of Advocacy are twofold: at home to make the Christian people obedient to the priesthood, and to execute priestly decrees upon heretics and sinners; abroad to propagate the faith among the heathen, not sparing to use carnal weapons. Thus does the Emperor answer in every point to his antitype the Pope, his power being yet of a lower rank created on the analogy of the papal…

Thus the Holy Roman Church and the Holy Roman Empire are one and the same thing seen from different sides; and Catholicism, the principle of the universal Christian society, is also Romanism…

Of course Voltaire, that great pioneer of the modern mindset, gibed that the HRE was “neither Holy, nor Roman, nor an Empire,” nor had been for many years.

Indeed, that was what any modern would see. But for most of its history, as an overarching framework of Christendom, it was at least as real to its denizens as “France,” “Germany,” or “Poland.”

As with Chivalry, any given guild, the “republic of letters” of the universities, or the Church herself, the Empire was as real as its subjects conceived it to be — no matter how much they might fight over or even against it.

Proof of this contention may be found in the work of Dom Prosper Gueranger, O.S.B., who, as both a 19th century Frenchman (and restorer of the Benedictines in that country as well as of Gregorian Chant throughout the Church), and, as an Ultramontane (he was instrumental in bringing about the 1870 definition of Papal Infallibility) may not be accused of partiality in this matter.

At the time of his writing, most commentators in English favoured the Medieval Emperors against the Popes because of their partiality toward Prussia and the nascent German Empire of Bismarck. This makes Dom Gueranger’s description of the imperial coronation in his entry for St. Leo III in his magisterial The Liturgical Year all the more telling:

Space fails us, or gladly would we here describe in detail the gorgeous liturgical function used during the middle-ages, in the ordination of an emperor. The Ordo Romanus, wherein these rites are handed down to us, is full of the richest teachings clearly revealing the whole thought of the Church.

The future lieutenant of Christ, kissing the feet of the Vicar of the Man-God, first made his profession in due form: he “guaranteed, promised, and swore fidelity to God and blessed Peter pledging himself on the holy Gospels, for the rest of his life to protect and defend, according to his skill and ability, without fraud or ill intent, the Roman Church and her ruler in all necessities or interests affecting the same.”

Then followed the solemn examination of the faith and morals of the elect, almost word for word the same as that marked in the Pontifical at the consecration of a bishop. Not until the Church had thus taken sureties regarding him who was to become in her eyes, as it were, an extern bishop, was she content to proceed to the imperial ordination.

While the apostolic suzerain, the Pope, was being vested in pontifical attire for the celebration of the sacred Mysteries, two cardinals clad the emperor elect in amice and alb; then they presented him to the Pontiff, who made him a clerk, and conceded to him, for the ceremony of his coronation, the use of the tunic, dalmatic, and cope, together with the pontifical shoes and the mitre.

The anointing of the prince was reserved to the Cardinal Bishop of Ostia, the official consecrator of popes and emperors. But the Vicar of Jesus Christ himself gave to the new emperor the infrangible seal of his faith, namely the ring; the sword, representing that of the Lord of armies, the most potent One, chanted in the Psalm; the globe and sceptre, images of the universal empire and of the inflexible justice of the King of kings; lastly, the crown, a sign of the glory reserved in endless ages as a reward for his fidelity, by this same Lord Jesus Christ, whose figure he had just been made. The giving of these august symbols took place during the holy Sacrifice.

At the Offertory, the emperor laid aside the cope and the ensigns of his new dignity; then, clad simply in the dalmatic, he approached the altar and there fulfilled, at the Pontiff’s side, the office of subdeacon, the servitor, as it were, of holy Church and the official representative of the Christian people. Later on, even the stole was given him: as recently as 1530, Charles V on the day of his coronation, assisted Clement VII in quality of deacon, presenting to the Pope the paten and the Host, and offering the chalice together with him.

The Imperial office was considered as sacred with Charlemagne and his successors as ever had been under Constantine, Theodosius, or Justinian. The Emperor was enrolled as a canon of St. John Lateran, and the church at Aix-la-Chapelle. He was considered to have some power over the weather by the people — in German today, fine sunny weather is still called Kaiserswetter.

Hence, as Dom Gueranger further tells us, this ceremony for the seventh lesson of Christmas Matins (dealing with the order of Caesar Augustus for the census which brought Mary and Joseph to Bethlehem) at St. Peter‘s:

This seventh Lesson, according to the Ceremonial of the Roman Church, is to be sung by the Emperor, if he happen to be in Rome at the time; and this is done in order to honour the Imperial power, whose decrees were the occasion of Mary and Joseph going to Bethlehem, and so fulfilling the designs of God, which he had revealed to the ancient Prophets. The Emperor is led to the Pope, in the same manner as the Knight who had to sing the fifth lesson; he puts on the Cope; two Cardinal-Deacons gird him with the sword, and go with him to the Ambo. The Lesson being concluded, the Emperor again goes before the Pope, and kisses his foot, as being the Vicar of the Christ whom he has just announced.

This ceremony was observed in 1468, by the Emperor Frederic III, before the then Pope, Paul II. This was echoed by the prayers of the Roman Missal, until 1955. Among the “Occasional Prayers, “ (sets of collects, secrets, and post-communions for various intentions, to be said by the priest after finishing the propers), we find the following, “For the Emperor:”

COLLECT O God, the Protector of all Kingdoms and in particular of the Christian Empire, grant to Thy servant our Emperor N. always to work wisely for the triumph of Thy power, that being s prince in virtue of Thy institution he may always continue mighty by virtue of Thy grace. Through Our Lord. SECRET Accept, O Lord, the prayers and offerings of Thy Church for the safety of Thy suppliant servant, and work prodigies habitual to Thine arm for the protection of nations faithful to Thee: that, the enemies of peace having been overcome, Christian peace may allow of Thy being served in security. Through Our Lord.

POSTCOMMUNION O God, Who hast prepared the Roman Empire to serve for the preaching of the Gospel of the Eternal King: present Thy servant our Emperor N. with heavenly weapons, that the peace of the Churches may not be disturbed by the storms of war. Through Our Lord.

Nor was this the only liturgical treatment the Emperor received. Twice a year, all Catholics came into contact with the Imperial idea. Among the Good Friday Collects was inserted the following:

Let us pray also for our most Christian Emperor N., that Our God and Lord may, for our perpetual peace, subject all barbarous nations to him. Let us pray. Let us kneel down. R. Arise. O Almighty and Eternal God, in Whose hands are the powers of all men and the rights of all Kingdoms; graciously look down upon the Roman Empire, that the nations that confide in their fierceness may be repressed by the power of Thy right hand. Through Our Lord. R. Amen. Then again, on Holy Saturday, during the Exsultet, the prayer blessing the Paschal Candle, the priest would chant:

Regard also our most devout Emperor N., and since Thou knowest, O God, the desires of his heart, grant by the ineffable grace of Thy goodness and mercy, that he may enjoy with all his people the tranquillity of perpetual peace and heavenly victory.

The Empire in the East fell to the Turks in 1453, after which the Russian Tsars claimed that post for themselves. The last Holy Roman Emperor abdicated in 1806, and this is generally accepted as the end of the Institution, although legal experts always point out that the abdication of a sovereign does not dissolve his throne.

This last Emperor had, two years earlier, declared himself Emperor of Austria. That line continued until 1918, when Bl. Charles I (of Austria—he would have been Charles VIII of the Holy Roman Empire), whose cause for sainthood is now complete, was forced off the throne at the behest of Woodrow Wilson.

It is rather ironic that the line begun with one Charles I, who is a Blessed, should have ended with another Charles I. The year before, Nicholas II abdicated the Russian throne. No longer does any government claim connexion with Constantine.

Valentin Tomberg on the Emperor

What is the importance of all of this history for the modern age? Well, as Valentin Tomberg put it:

The post of the Emperor…what an abundance of ideas concerning the post—its historical mission, it functions in the light of natural right, and it role in the light of divine right – of the Emperor of Christendom are to be found amongst medieval authors!

As it is suitable that the institution of a city or kingdom be made according to the model of the institution of the world, similarly it is necessary to draw from divine government the order of the government of a city — this is the fundamental thesis advanced by St. Thomas Aquinas (De regno xiv, 1).

This is why the authors of the Middle Ages could not imagine Christianity uster an Emperor, just as they could not imagine the Universal Church without a Pope. Because if the world is governed hierarchically, Christendom* or the Sanctum Imperium cannot be otherwise.

Hierarchy is a pyramid which exists only when it is complete. And it is the Emperor who is at its summit. Then come the kings, dukes, noblemen, citizens, and peasants. But it is the crown of the Emperor which confers royalty to the royal crowns from which the ducal crowns and all other crowns in turn derive their authority.

The post of the Emperor is nevertheless not only that of the last (or, rather, the first) instance of sole legitimacy. It was also magical, if we understand by magic the action of correspondences between that which is below and that which is above.

It was the principle itself of authority from which all lesser authorities derived not only their legitimacy but also their hold over the consciousness of the people.

This is why royal crowns one after another lost their uster and were eclipsed after the imperial crown was eclipsed. Monarchies are unable to exist for long without the Monarchy; kings cannot apportion the crown and sceptre of the Emperor among themselves and pose as emperors in their particular countries, because the shadow of the Emperor is always present.

And if in the past it was the Emperor who gave lustre to the royal crowns, it was later the shadow of the absent Emperor which obscured the royal crowns and, consequently, all the other crowns — those of dukes, princes, counts, etc. A pyramid is not complete without its summit; hierarchy does not exist when it is incomplete. Without an Emperor, there will be, sooner or later, no more Kings. When there are no Kings, there will be, sooner or later, no nobility. When there is no more nobility, there will be, sooner or later, no more bourgeoisie or peasants. This is how one arrives at the dictatorship of the proletariat, the class hostile to the hierarchical principle, which latter, however, is the reflection of divine order. This is why the proletariat professes atheism.

Europe is haunted by the shadow of the Emperor. One senses his absence just as vividly as in former times one sensed his presence. Because the emptiness of the wound speaks, that which we miss know how to make us sense it.

Napoleon, eye-witness to the French Revolution, understood the direction which Europe had taken — the direction towards the complete destruction of hierarchy. And he sensed the shadow of the Emperor. He knew what had to be restored in Europe, which was not the royal throne of France — because Kings cannot exist long without the Emperor — but rather the Imperial throne of Europe. So he decided to fill the gap himself. He made himself Emperor and he made his brothers kings. But it was to the sword that he took recourse. Instead of ruling by the orb — the globe bearing the cross — he made the decision to rule by the sword. But, “all who take up the sword will perish by the sword.” Hitler also had the delirium of desire to occupy the empty place of the Emperor. He believed he could establish the “thousand-year empire” of tyranny by means of the sword. But again —“all those who take up the sword will perish by the sword.”

No, the post of the Emperor does not belong any longer either to those who desire it or to the choice of the people. It is reserved to the choice of heaven alone. It has become occult. And the crown, the sceptre, the throne, the coat-of-arms of the Emperor are to be found in the catacombs…in the catacombs — this means to say: under absolute protection.

We are dealing with deep and strange matters here. But the fact remains that the Empire, both East and West, is gone. The vision of the Holy Empire haunted the soldiers and administrators who pioneered the Spanish, Portuguese, French, and British colonial Empires.

Of the latter, Ernest Barker wrote in his article “Empire,” for the 1911 Encyclopaedia Britannica:

The British Empire is, in a sense, an aspiration rather than a reality, a thought rather than a fact; but, just for that reason, it is like the old Empire of which we have spoken; and though it be neither Roman nor Holy, yet it has, like its prototype, one law, if not the law of Rome — one faith, if not in matters of religion, at any rate in the field of political and social ideals.”

The First World War, three years later, would weaken that Empire fatally, even as it would destroy the German Empire, the other great Protestant exponent of the Imperial idea.

In any case, across Europe, and in Latin America, Canada, the Philippines, and elsewhere, in institutions, customs, and buildings, the mark of the Empire can be seen. Even in our own United States, in places settled before Independence or by the French and Spanish, there yet linger traces; visible only to those who know what to look for, perhaps, (like the double-eagle over the Spanish Governor‘s Palace in San Antonio, Texas), but still present.

In many ways, starting with the United States and their electoral college, such federal unions as Canada, Australia, South Africa, Mexico, Brazil, Argentina, and India all owe elements of their constitutions to the Empire, and its idea of unity within diversity. The founders of the European Union hoped that their creation would, in some way, take its place, as did all the Popes from Pius XII to Benedict XVI. Instead, we have what we have.

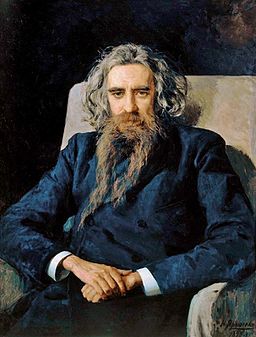

Vladimir Soloviev on the Organic Union of Church and State

But does this matter? Indeed it does, especially as the aging hippies of Brussels seem hell-bent on taking the place of Bonaparte and Hitler, albeit in a dull, “compassionate” kind of way. Back in 1900, the great Russian philosopher, Vladimir Soloviev, declared:

For lack of an Imperial power genuinely Christian and Catholic, the Church has not succeeded in establishing social and political justice in Europe. The nations and states of modern times, freed since the Reformation from ecclesiastical surveillance, have attempted to improve upon the work of the Church. The results of the experiment are plain to see.

The idea of Christendom as a real though admittedly inadequate unity embracing all the nations of Europe has vanished; the philosophy of the revolutionaries has made praiseworthy attempts to substitute for this unity the unity of the human race — with what success is well known.

A universal militarism transforming whole nations into hostile armies and itself inspired by a national hatred such as the Middle Ages never knew; a deep and irreconcilable social conflict; a class struggle which threatens to whelm everything in fire and blood; and a continuous lessening of moral power in individuals, witnessed to by the constant increase in mental collapse, suicide, and crime—such is the sum total of the progress which secularised Europe has made in the last three or four centuries.

The two great historic experiments, that of the Middle Ages and that of modern times, seem to demonstrate conclusively that neither the Church lacking the assistance of a secular power which is distinct from but responsible to her, nor the secular State relying upon its own resources, can succeed in establishing Christian justice and peace on the earth.

The close alliance and organic union of the two powers without confusion and without division is the indispensable condition of true social progress.

It remains to enquire whether there is in the Christian world a power capable of taking up the work of Constantine and Charlemagne with better hope of success. More recent authors have written in much the same vein. Journalist Gary Potter, in his 1991 work, In Reaction, wrote:

Words express ideas, and some of them now being quoted signify notions likely to be totally foreign to anyone unfamiliar with history prior to a few decades ago: “world emperor,” “imperial office,” AEIOU itself. This is not the place to lay out all the history needed to be known for thoroughly grasping the notions. However, the principal one was adumbrated by Our Lord Himself in the last command His followers received from Him: to make disciples of all the nations. In a word, the idea of a universal Christian commonwealth is what we are talking about.

To date, it has never existed. Today there is not even a Christian government anywhere. However, from the conversion of Constantine until August, 1806 — with an interruption (in the West) from Romulus Augustulus in 476 to Charlemagne in 800 — there was the Empire. It was the heart of what was once known as Christendom. Under its aegis serious European settlement of the Western Hemisphere began and the Americas’ native inhabitants were first baptized, which is why the feather cloak of Montezuma is to be seen today in a museum in Vienna.

After 1806 a kind of shadow of the Empire, the Austro-Hungarian one, endured until the end of World War I, when its abolition was imposed as a condition of peace by U.S. President Woodrow Wilson. Since 1438, when Albert V, cousin of Frederick III, was crowned Roman Emperor, all the Emperors were Habsburgs.

The last was Archduke Otto’s father, Karl. The malaise of Europe and her daughters is in great part traceable to her renunciation of the Faith that created her. But that renunciation itself owed much to the death of the Imperial idea, and the philosophical basis upon which it rested. The horrors Soloviev described have only worsened — not only on the national and continental levels, but the personal one as well.

Given this difficulty, and the others concerning demographics and Islam earlier mentioned, just what is to be done? It is evident that the Blairs and Zapateros are never going to wake up to reality (although, if Blair does convert to Catholicism after leaving office — which I hope for his sake he will — he will probably spend his dotage condemning the evils resulting from his own policies, without ever noticing their origins).

It is just as evident that the rulership of Europe committed to the EU becoming an ever more encompassing superstate. It is truism to say that “the rulers rule and the subjects serve,” but they do in all societies, and never more than in the 21st century. In all likelihood, things will continue along the route they are proceeding, until at last the EU is a true prison of the nations, or Islam cleans Europe’s cuckoo clocks in a bath of blood. Neither is a particularly appetizing outcome, in all honesty.

Towards a Counter-Revolution

But “while there is life, there is hope,” to quote a cliché, and much can yet be done. The first thing is an acceptance of reality. Despite the best (and truly noble) efforts of the Eurosceptics — and occasional partial and temporary victories here or there — I think that it must be admitted that the European institutions at Brussels, Strasbourg, and Luxembourg, with their attendant bureaucracies, are not going away, nor are their hideous buildings. In a political sense, then, the struggle for control of these bodies must be begun in earnest. What is required is a sort of political counter-revolution.

But counter-revolutions most often fail because their leadership (and sometimes their rank and file) have no real political ideas or ideology of their own, save opposition to the usurpers. Indeed, they often share many of their opponents’ basic beliefs, so successful has the revolution become. Moreover, conservatives, men of the right, call them what you will, not usually driven by hatred and envy, are usually not driven much at all. Why bother about the cause and some future, when the present can be so enjoyable?

Yet if Europe is not to sink beneath a sea of either blood, boredom, or both, those with the love of her as she was and to some degree yet remains at heart must be animated by a desire for political success the equal of her present rulers. Thankfully, the bits and pieces are still around to be picked up and perhaps re-sewn into a new garment.

The EU has divided European Conservatives in twain. On the one hand, there are the Eurosceptics, who quite rightly fear the loss of national, regional, and provincial liberties. On the other, Conservative proponents of an integrally united Europe, such as the Paneuropa Union, invoke the Crown of Charlemagne for their work.

These two sets must realise that in reality, they compliment one another, and ought not to be opposed. France and Estonia, Asturias and Bavaria, all need to be preserved as fully functioning entities with legitimate lives and ethoi all their own; but this understanding needs to be blended with a true realisation of Europe’s legitimate cultural and spiritual unity, the need in to-day’s world for this unity to be expressed in a concrete way (especially in terms of trade and defence), and the importance of the civilisation that unity has engendered for the rest of the world — especially, but far from solely, the daughter nations.

Nor should these realisations be restricted by race. Many a Goan, Tahitian, or Cape Coloured is a better European than those who crawl the corridors of power in the Mother Continent. Much the same could be said for the Christians dying for their Faith in China, the Sudan, India, Pakistan, or Indonesia.

The Religious Dimension of Europe

This brings up another point, doubtless an uncomfortable one for many. That is the religious dimension. As earlier quoted, dear old Belloc declared, “the Faith is Europe, and Europe is the Faith.” Now, as many of the aforementioned Christians in Africa and Asia might tell you, there is some oversimplification there — but only some.

Since Europe has, since 1945, done her best not to be the Faith, she has done an extremely effective job of being nothing at all. But Islam’s challenge cannot be countered with mere affirmations of an empty and weary pluralism. A positive thing can only be checked by another positive thing, not a negation.

Nor can this be a mere question of, as some churchmen have put it, of Europe regaining a sense of her Christian “roots” and “values,” any more than Islamic “roots” and “values” are posing a serious threat to the West. It is the conviction of individual Muslim militants that their personal salvation is bound up with their political and military actions that make them formidable, even as it was similar conviction on the part of Christians that allowed first the establishment of Europe herself, and then her expansion across the globe.

Cynical historians may point to the part that lust for power and thirst for wealth played in these developments, and they are certainly correct to a degree. But those elements alone would never have brought armies of settlers across the seas, nor battalions of missionaries to exceedingly unpleasant climes. However given up to the worship of Mammon in all his forms my current home may be, it was neither the quest for power or wealth that led to the founding of this City of Angels.

Even though such figures of the Right as Maurras, Bolingbroke, and Santayana might have been comfortable as unbelievers, citing religion’s mere utility in preserving the culture and institutions they loved, personal belief is required, if the Europe of the future is to be one worth living in.

It was for this reason that, in his homily on the occasion of the beatification of Emperor Charles I of Austria, John Paul II declared

From the beginning, the Emperor Charles conceived of his office as a holy service to his people. His chief concern was to follow the Christian vocation to holiness also in his political actions. For this reason, his thoughts turned to social assistance. May he be an example for all of us, especially for those who have political responsibilities in Europe today!

I will outrage modern sensibilities even further, and say that a vague “Christianity” will not serve for this purpose. Rather, that Church that gave birth to Christendom in the first place is the only one that can truly serve as a religious basis for a revivified Europe. But for that to happen, she must regain the sense of self she has dissipated since the 1960s — a need her current Pontiff and the rising generation of clerics understand very well.

Catholics, however, if they are to be politically effective, must learn to think once more of personal salvation, and of political, social, and charitable action as a means to that end. Many of the newer orders and movements in the Church, as well as revivals of older ones (like the Templars in Italy and the Hieronymites in Spain) are hopeful signs in that direction.

In this light, ecumenism will have to be rethought. On the one hand, dialogue with moribund ecclesial bodies that are no longer sure of doctrinal realities is pointless. But dialogue in search of union with such groups as the Traditional Anglican Communion, the Hochkirchliche Vereinigung, and the Nordic Catholic Church (which body recently received the Apostolic Succession from the Polish National Catholics, with Papal approval and encouragement) assumes a real urgency. All of that is even truer as regards the Orthodox and “lesser” Eastern Churches.

The rediscovery of pilgrimages and refurbishing of pre-Reformation shrines in Northern Europe that has gone on since 2000 is a promising development along these lines. Official bodies (such as the European Institute of Cultural Routes) and private ones (like the Confraternities of St. James in various countries) have done much to revive the pilgrims’ routes, especially to Compostella, that did so much to bring the peoples of Catholic Europe together in both movement and devotion.

We also need to regain a love for Europe as Christendom, for our own country’s heroes and traditions, as well as those of the others. From Aetius and Arthur to von Stauffenberg, the great ones who defended Europe against her enemies, and who spread her religion and civilisation throughout the world, should be vindicated. No longer ought we to apologise for the Crusades (save for when folly or treachery on the part of those paladins frustrated their high purpose).

We should honour, as part of our common heritage, folk like the Chouans and Vendeens in France, the Cristeros in Mexico, the Cavaliers and Jacobites in the British Isles, the Carlists in Spain, the Pontifical Zouaves, and on and on. It needs also to be remembered that, at their best, they fought under the standard of Jesus and Mary; at their worst, they were still better, as men, than the “heroes” the modern world offers us, such as Norman Bethune, Margaret Sanger, and Che Guevara.

Christendom Awake!

This being the case, it would be well for theologians and others concerned with European institutions and holding at least some of the views heretofore outlined to take another look at the vision of the Empire. This too is already happening. Fr. Aidan Nichols, O.P., for example, in his Christendom Awake! would call the Holy Roman Empire back into being:

Catholicism, as Orthodoxy, has, historically, regarded the monarchical institution in this light: raised up by Providence to safeguard the natural law in its transmission through history as that norm for human co-existence which, founded as it is on the Creator, and renewed by him as the Redeemer, cannot be made subject to the positive law, or administrative fiat, or the dictates of cultural fashion. Let us dare to exercise a Christian political imagination on an as yet unspecifiable future.

The articulation of the foundational natural and Judaeo-Christian norms of a really united Europe, for instance, would most appropriately be made by such a crown, whose legal and customary relations with the national peoples would be modelled on the best aspects of historic practice in the (Western) Holy Roman Empire and the Byzantine “Commonwealth” — to use the term popularised by Professor Dimtri Obolensky.

Such a crown, as the integrating factor of an international European Christendom, would leave intact the functioning of parliamentary government in the republican or monarchical polities of its constituent nations and analogues in city and village in other representative and participatory forms. As the Spanish political theorist Alvaro D’Ors defines the concepts, power — that is, government — as raised up by the people can and should be distinguished from authority.

Power in this sense puts questions to those in authority as to what ought to be done. It asks whether technically possible acts of government, for co-ordinating the goals of individuals and groups in society, chime, or do not chime, with the foundational norms of society, deemed as these are to rest on the will of God as the ultimate power of the shared human goal. Authority, itself bereft of such power, answers out of a wisdom which society can recognise.

Given that Fr. Nichols belongs to a rather influential school of theology, it is far from impossible that some future Pope may well see the need for the sort of restoration here envisaged. If such a Pontiff mounts the throne of St. Peter at a time when the then-leadership of the European Union feel a need to animate their machinery with a soul, we may well see something of a new Empire emerge.

This development would profoundly affect the European daughter nations of the Americas, Australasia, and elsewhere; moreover, it might well be the only real answer Western Civilization can make to a resurgent Islam.

Eurosceptics, Pan Europeans, Catholic activists, neo-Imperialists — none of these need agree on all points at this stage. What they must do is talk with each other and write up their ideas. A body of discourse should be built, “knitting up the fragments” as it were, of past traditions and present needs.

Above all, folk minded in this direction who do not care to go into European or national politics (or find no opportunity thereat) should consider two equally or even more important areas of endeavour: academia, and the production of reference materials, such as encyclopaedias and dictionaries. Samuel Johnson saw the importance of this latter area of the conflict, and it has been well said that the history of the world, at least its English-speaking component, would have been far different had the Encyclopaedia Britannica been produced at Oxford rather than at Cambridge.

All of this labour in the macrocosm may well take generations, even as the opposition’s work did — and it could certainly be that we do not have the time. Worse still, most of us will never play any role at all on the Continental or National stage, whether in a political, academic, or literary role. What, then about the rest of us? Ought we simply to sit back and hope for the best?

By no means! Each of us needs to cultivate a personal Faith, simply because, presuming we have souls, each of us will be around far longer than the current political scene, and our own damnation or salvation depends upon it. Beyond that, though, the creeping of “that Hideous strength” into every corner of Europe and the West requires resistance — resistance in our own particular sphere, in which we find ourselves.

Whether it be larger issues, such as abortion or euthanasia, or smaller local ones, such as protection of the built heritage or unspoiled areas, looking after the poor or disabled, defending the Monarchy, hunting, or other traditional institutions and practises, or just fighting for the right of local cheese or sausage makers to continue their craft as their fathers did, we each have a battle to fight.

But, if we are in Europe, we should remember that we are fighting in what appear to be parochial conflicts the local battle of a great war, and get in touch with similarly-engaged folk throughout the Continent, exchanging ideas and tactics. The threat is Europe-wide, so should be the defence.

What of the future? Who knows? Should ever something along the lines of Fr. Nichols’ proposal become likely, the case can be made that the abdication of Francis II in 1806, which is generally considered to be the act that ended the Empire, simply began a new interregnum, comparable to that opened by Romulus Augustulus’ renunciation of the throne in 476 A.D., and concluded by Charlemagne’s coronation in 800 (although, to be sure, the Eastern Empire continued uninterruptedly all that time). As Viscount Bryce himself points out:

Great Britain had refused in 1806 to recognise the dissolution of the Empire. And it may indeed be maintained that in point of law the Empire was never extinguished at all, but lived on as a sort of disembodied spirit. For it is clear that, technically speaking, the abdication of a sovereign destroys only his own rights, and does not dissolve the state over which he presides. Perhaps the Elector of Saxony might, legally, as Imperial Vicar during an interregnum, have summoned the electoral college to meet and choose a new Emperor. Bryce, op. cit., p. 416, note o.

What made Great Britain’s refusal of recognition of the Emperor’s act so important is that her King, at that time Elector of Hanover, had a voice in the governance of the Empire and a vote in the election of any future Emperor. But much the same case is made by Klaus Epstein:

While there is no question that Francis was personally entitled to abdicate a crown he was no longer willing to wear, he certainly had no constitutional power to dissolve the fabric of imperial obligation per se. The empire, like all sovereign states, was intended to be perpetual and the emperor had sworn to maintain it to the best of his ability. He broke his coronation oath when he declared it dissolved, and he failed to consult the Stände assembled at Regensburg about his highly irregular procedure. One can argue, therefore, that the imperial death warrant was technically ultra vires and therefore null and void, and that the empire “legally” continued to exist after 1806. (The Genesis of German Conservatism, p. 668)

Should such a Pontiff emerge as we just spoke of, given that by the Empire’s law the Pope was in fact “Imperial Vicar” during an interregnum (pace Viscount Bryce), he would have a firm legal base from which to conjure the Empire back into existence.

But that is all speculation. Should Europe be overwhelmed by external enemies or collapse into some horrible Orwellian nightmare, or both, the Faith and the notion of the Empire will survive her. No doubt a new civilisation will arise on her ruins, even as she did on those of old Rome.

Yet there will be continuity of some kind; it may be that Brazilians or Congolese will free the Mother Continent from her occupiers, and retransform her cathedrals from mosques into churches once more, as happened so many times in Spain and Hungary.

In truth, while we may be confident of future victory, at this time we can no more predict what form that victory will take than Ss. Ambrose and Augustine could have foretold Clovis and Justinian.

But what of us as individuals? What have we to look forward to? The work that has been laid before us, done with all our might, as part of our quest for Heaven. In one way, Bl. Charles of Austria was a complete failure. Nothing he tried in the political sphere succeeded: World War I did not end early, his peoples were not able to settle down as equal partners in one house, and even his attempts to regain Hungary came to miserable ends. He died a tubercular exile on a far-off island. Bl. Thomas Percy tried, in the Rising in the North, to restore England’s Church and State; he failed, and was executed in the Tower of London. St. Louis IX attempted to re-ignite the Crusades, and died a prisoner of the Turks.

The Church did not raise these men to her altars for their political efforts, but for their personal holiness; nevertheless, those efforts played a role in their ascension to Heaven. So it may be for us, God willing, regardless of whatever may come from our poor actions this side of the grave.

The Crown of Charlemagne rests in Vienna‘s Hofburg, while his throne is in the upper gallery at Aachen‘s cathedral. Though the last Imperial claimant went into exile in 1918, the ghost of the Empire remains; it will do so, so long as there are folk of Faith and valour left upon the Earth. Those who come after may well look more like Indians, Chinese, or Africans than ourselves, but they will be worthy successors of Arthur, Charlemagne, and Godefroi de Bouillon all the same.

Buying Books at Amazon Through These Links Gives Us a Commission. This Supports Our Apostolate. Thank You if You Can Help Us Like This!

Comments

comments are currently closed

6 responses to “GUEST PIECE: Europe and the Empire by Charles A. Coulombe”

[…] Peladan’s works are hardly available in English. And for those wishing to understand Tomberg’s own Ultramontane revolution, I particularly recommend Belloc, who honestly strikes me as hermetic genius. I do not use the last word lightly. Pondering the vast sweep and originality of his 153 books leaves me in no doubt of that whatsoever. Here I would also recommend reading a modern author, Charles A. Coulombe, of French descent himself, who seems something of a modern day heir of Bellocianism. Moreover, Coulombe’s political thinking is redolent of Tomberg’s politics in many respects. (I enter into a comparison of Tomberg and Coulombe in my introduction to a numinous piece from Coulombe here.) […]

[…] And unsurprisingly I’ve done numerous pins now for the great Hilaire Belloc and Charles A. Coulombe. […]

[…] Europe and the Empire — by Charles A. Coulombe at Cor Jesu Sacratissimum […]

[…] Yes, Charles Coulombe, I am indebted to you, along with the great Valentin Tomberg and Hilaire Belloc, for helping to set me free … (Indeed, I had also discovered Tomberg’s Catholic legal-political thought in Spain, where I began a series of posts devoted to them. I was also struck by the many parallels between Tomberg’s and Coulombe’s political thinking regarding Christendom, as I have expanded on here.) […]

The only power taking steps in this direction, however small they be, is the Russian Federation, in close cooperation with the Orthodox Church. Yes, it is still far from actualizing the Christian imperial ideal, but the fact developments appear to be slowly heading in this direction at all can be deemed miraculous when we remember that the Soviet Union was one of the worst atheist regimes in the world only a few decades ago, and that the other European powers continue on the path to de-Christianization. Certainly we are here seeing the effect of…

We are reminded of the Virgin Mary’s call at Fatima for the consecration of Russia to Her Immaculate Heart and its conversion, in which it was implied that Russia instead of being a leading persecutor of Christianity, would perhaps become its foremost defender. Was Our Lady indeed hinting that Russia might become the power to correspond most closely with the Christian Empire in the last days?

We should obey the request of the Blessed Virgin and push more than ever for the consecration of Russia. It is almost unimaginable today how the nations of the EU will rise as defenders of Christendom, but it is easier to envision that Russia can be pushed further in that direction, enough to become a balancing influence in the dangerous Godless world-order today, because the Orthodox Church in Russia is expanding and Putin is already making decisions for its protection that would be almost unthinkable in the EU. I don’t know who Putin really is or why he is doing this, but the fact is, he’s doing it. Whatever be the dark sides of Russian power, we should struggle to have such a process continue.

If Russia can be made an Orthodox Christian power, that would be a great aid for all of Christendom in the dangerous times ahead, approaching global rule by Antichrist.

My suggestion is to make Russian Orthodox believers realize the importance of Fatima for Russia. To plant this seed among them and have it grow into a movement may be what we need in order to finally have Russia be consecrated properly. Such a manifestation would remind the world of the message and miracle of Fatima, and also reinforce the principle of a holy Christian mission for Russia, a special election by the Theotokos, which can become the new Russian idea.

I said that: “If Russia can be made an Orthodox Christian power, that would be a great aid for all of Christendom in the dangerous times ahead, approaching global rule by Antichrist.” But it should be added that there may be dark, alluring temptations hiding within such a scenario also. For there are ways in which such a power, as a wolf in sheep’s clothing, may end up seducing and leading Christians astray by compromising them through identification with a corrupt worldly power, perhaps causing as much, if not more, harm to Christianity as it offers protection to it. Russia can easily become a pseudo-religious Fascism that only exploits religion in service of Russian stateism, nationalism, militaristic imperialism and collectivism, reducing Christians supporting it to partisans obsessed by an ideological spectre that is worldly and profane at heart. (A strategy of seducing and compromising conservative Christians is part of the strategy of the Trump regime too.)

Nevertheless, there may be a mysterious destiny for Russia implied in the Fatima message, a positive role it is meant to play in the last days, so I still stand by what I said. This strategy should be attempted. Maybe you will have some time to reflect on it.

The world is situated right at the edge of the abyss now. So many destructive developments are converging. For example, see the genome editing technology that was awarded the Nobel prize these days. Now they are literally able to ‘cut out’ and ‘paste in’ DNA in living human beings!

[…] Europe and the Empire — by Charles A. Coulombe at Cor Jesu Sacratissimum […]