By John R. G. Hassard

Introduction:

Here is the second instalment of another old Nineteenth Century Catholic book in our Tridentine Archive. The book is the 1878 Life of Pius IX by John R. G. Hassard and appears here in nine chapters:

- Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 1: Early Years in Christendom Despoiled

- Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 2: The Carbonari and Other Secret Societies

- Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 3: The Conclave Elects a New Pope

- Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 4: Conspiracy, War and Revolution

- Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 5: Annexation of the Papal States

- Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 6: Counter-Revolution and the Syllabus of Errors

- Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 7: Ultramontanism and the First Vatican Council

- Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 8: The Seizure of Rome and the Last Stand of the Papal Zouaves

- Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 9: A Prisoner of the Vatican

In this chapter, we start to encounter one of the outstanding themes of Hassard’s work – that of the secret societies fermenting revolution in Nineteenth Century Europe.

To appreciate Hassard’s claim, it is necessary to know something of the European history of that epoch.

Key to this understanding is recognition of the earth-shattering nature of the French Revolution of 1789, proclaiming a then-very liberal agenda of Liberty! Equality! Fraternity! – whilst initiating a period of bloodshed and genocide in which hundreds of thousands of Catholics loyal to the Church and Throne were massacred.

Then came the Napoleonic wars across Europe lasting till 1815. Whilst Napoleon brought the worst excesses of the French Revolution to an end, it might be said – if somewhat simplistically in this short space – that he nonetheless exported French Revolutionary ideas across Europe as he conquered countries like Spain, Austria and the independent states making up what has now become the state of Italy.

Tremendous destruction was set loose and even when order was restored in Europe in 1815 and the Church and monarchy could flourish once more, revolutionary movements against Altar and Throne continued to spring up in countries like Spain and France (which experienced a second revolution in 1830).

All this Hassard – along with countless others! – believes is deeply indebted to the work of masonic-type secret societies such as the Illuminati and the Carbonari.

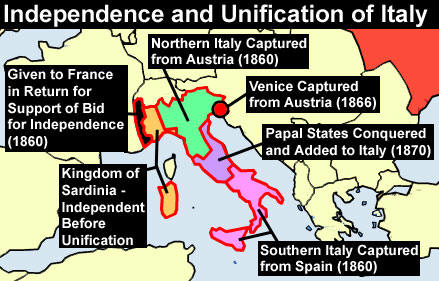

The picture becomes even more complicated when we remember that before 1870, there was no united Italian nation. Instead, the Italian peninsula was divided amongst several reigning powers.

There were, of course, the Papal States which had been ruled by the Popes for centuries. There were also smaller independent Italian states such as the duchies of Tuscany and Parma. Finally, parts of what is now Italy today were commanded by Spain and Austria.

During the Nineteenth Century, a movement of Italian unification arose, commonly known as the Risorgimento. That movement is closely linked with such revolutionary figures as Mazzini, Garibaldi and Cavour.

All of whom – amongst many other largely-forgotten names – we meet in the pages of Hassard’s book and now in the webpages of this site.

The interested reader may be referred to either the old 1917 Catholic Encyclopaedia (available online here) or Wikipedia and other sources on the web to explain who these men were and what they did.

We cannot enter into that level of detail here. Suffice it to say that during the reign of Bl. Pius IX (1846-1878), the Risorgimento succeeded.

Through interlinked processes of insurrection, war and conquest, the once-separate Italian entities were fused to become form the state we know as Italy today.

A map of these processes – though somewhat simplified – may help the modern reader to understand:

Today, many a reader will likely consider all this in anything but positive terms – scarcely realising how much vast numbers of the Italian population were once staunchly opposed to the revolutionary Risorgimento.

For they feared, among other things, that Christian civilisation would be destroyed.

And given how many priests were killed, how many convents and monasteries were ransacked, how many churches were destroyed by the Risorgimento – they had every right to be frightened …

The Risorgimento was not purely and simply a quest for Italian unification. As Hassard observes:

It is certain that the sentiment of unity was not the origin of the revolutionary movement in the Italian States, and will not be its end. The movement was active before national unity was thought of and is still active after national unity has been attained.

Again Hassard, like countless others of his time, believes that the Risorgimento was only possible through conspiracy and the skulduggery of masonic-type groups such as the Carbonari and the Illuminati – among others.

How true is this understanding?

To truly answer this question is beyond almost any man, except perhaps the most diligent, competent and unbiased of historians and researchers.

Alas! An unbiased historian is the rarest of creatures!

I can only offer my own opinion, dear Reader – with my own biases.

I think the conspiracy claims of Hassard are worth listening to. That is why we publish them here.

However, ‘worth listening to’ is not the same as as a full endorsement of everything Hassard says in these (web) pages. Again, I myself am far, far from competent to judge these matters.

I only know that today’s liberal sceptical historians – usually hostile to Catholicism – are also far from competent to judge these matters.

People are all-too-easily written off these days as cranks or conspiracy nuts.

So be it – then the great Popes of the Nineteenth Century must also be cranks and conspiracy nuts. For great men such as Bl. Pius XI or Leo XIII frequently warned of the dangers of such masonic groupings to the world.

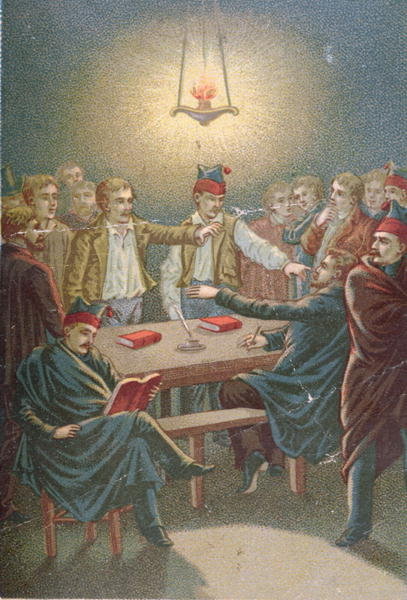

What Hassard writes below is mainly concerned with the Carbonari in Italy. Of these, the 1917 Catholic Encyclopaedia writes:

The name of a secret political society, which played an important part, chiefly in France and Italy, during the first decades of the nineteenth century. …

The association originated as the eighteenth century passed into the nineteenth; it was one of the results of the political movement which accompanied the great French Revolution and of the political principles that were proclaimed at that time ..

The name “Carbonari” was adopted from the charcoal-burners, so also in their secret intercourse they made use of many expressions taken from the occupation of charcoal-burning …

The Carbonari were divided into two classes: apprentices and masters. No apprentice could rise to the grade of a master before the end of six months. The members made themselves known to one another by secret signs in shaking hands. These signs for masters and apprentices were unlike.

One of the underlying principles of the society, it is true, was that the “good brotherhood” rested on religion and virtue; but by this was understood a purely natural conception of religion, and the mention of religion was absolutely forbidden. In reality the association was opposed to the Church. …

The members belonging to each separate district formed a vendita, called thus from the place of assembly. At the head was the alta vendita, to which deputies were chosen from the other vendite.

A small hatchet was the distinguishing symbol of a master, the apprentices were indicated by a little fagot worn in the button-hole. Initiation into the society was accompanied by special ceremonies which, in the reception into the grade of master, imitated the Passion of Christ in a manner actually blasphemous.

The members were bound by a frightful oath to observe absolute silence concerning whatever occurred in the vendita. The similarity between the secret society of the Carbonari and Freemasonry is evident. Freemasons could enter the Carbonari as masters at once.

The openly-avowed aim of the Carbonari was political: they sought to bring about a constitutional monarchy or a republic, and to defend the rights of the people against all forms of absolutism. They did not hesitate to compass their ends by assassination and armed revolt …

On 15 August, 1814, Cardinals Consalvi and Pacca issued an edict against secret societies, especially against Freemasonry and the Carbonari, in which all were forbidden under severe penalties to become members of these secret associations, to attend their meetings, or to furnish a meeting-place for such. …

The Carbonari … secretly continued agitation against Austria and the governments in friendly connection with it. They formed, even in Rome, a vendita, published in the press the most violent accusations against the lawful rulers, and won over to their cause members of deposed sovereign families, among whom was Prince Louis, later Napoleon III.

Pope Pius VII issued a general condemnation of the secret society of the Carbonari, 13 September, 1821. The association lost its influence by degrees and was gradually absorbed into the new political organizations that sprang up in Italy; its members became affiliated especially with Mazzini’s “Young Italy”.

We cannot say much more in this short space. More will be said in the succeeding introductions to this series …

But the interested reader must follow up these matter for himself.

Again, either the old Catholic Enyclopedia of 1910 (online here) or Wikipedia can explain much that is forgotten in these webpages – although Wikipedia, I think, certainly suffers the biases of contemporary liberal historiography. Caveat Lector!

Let us now turn to Hassard, who after considering the early years of Cardinal Mastai – the future pope, Bl. Pius IX – now turns his attention to the political situation of 1846, the year of the conclave in which Cardinal Mastai was elected pope.

On Anti-Christian Conspiracy

WHEN Cardinal Mastai drove out of the city of Imola in June, 1846, and, followed by the prophetic cries of the admiring populace, ‘Long live our Pope!’ proceeded to Rome to attend the conclave, he left forever the peaceful life which had become dear to him, and entered upon a long course of anxiety and pain.

The aspect of almost the whole world was threatening. The anti-Christian conspiracy which had kept Europe in turmoil for nearly a hundred years was ripe for revolution and the least acute observer could see that a great political crisis was near at hand.

It might be said without much exaggeration that men stood for a moment with ear intent and bated breath waiting for the inevitable explosion.

It would be idle, in the compass of this little book, to explore the causes of the convulsions of 1830-1848. They were complex and deep rooted.

The revolutionary propaganda of this period found almost every country of Europe ready for combustion.

Some states were rotten with social and moral disorders of long standing; some, like Poland, writhed under an oppression which moved the sympathies of the whole world.

Some fretted under the restrictions of antiquated forms of government unsuited to the wants of an expanding society.

Some were cursed with bad rulers, some with an infidel population.

The vitality of the principles of the great French Revolution had not been exhausted. On the contrary, they had been disseminated all over the continent, and everywhere they bore fruit.

Recent writers have represented the pontificate of Pius IX as a prolonged struggle between priestly despotism and the unconquerable popular yearning for national unity.

But it is certain that the sentiment of unity was not the origin of the revolutionary movement in the Italian States, and will not be its end. The movement was active before national unity was thought of and is still active after national unity has been attained.

The Carbonari, the Illuminati and other Masonic Type Societies

The central influence which animated and directed the tendencies towards revolt in the various countries of Europe was the conspiracy of the secret societies.

There was not a corner of the continent in which their power was not felt and at the death of Gregory XVI they had become one of the chief forces in European politics.

Intimately allied with Freemasonry, their origin dates back to a remote, uncertain period. They were strong and dangerous before the world suspected their existence.

The Illuminati, founded by Weishaupt among the Masonic lodges of Bavaria, and aiming at the most radical disintegration of society as well as the overthrow of Christianity, are regarded as the immediate progenitors of the secret societies of our day.

They were formidable a hundred years ago. From Bavaria, Illuminism was introduced into Austria, Saxony, Holland, Italy, and Switzerland; it; was carried to Paris by Mirabeau, who was initiated in Germany and it was united with Masonry all over France.

Carbonarism, the worst of its numerous offspring, was organized in the Neapolitan States about 1814 or earlier, and in five or six years it not only spread over the whole Italian peninsula but obtained a firm foothold in France and Spain.

Other secret societies the Adelphi, the Federati, the Decisi, the Guelphs, the Reformed Emancipated Patriots were formed in various parts of Italy, all pursuing the same revolutionary and anti-Christian objects, and all more or less regu larly affiliated both with the parent Carbonari and with the Masonic lodges.

Yet while they co-operated in the work of destruction they were utterly at variance in their ideas of what ought to come after.

The Italians were so far from regarding themselves as one people that a real union did not occur to them as desirable.

And even when the Carbonari attempted in 1831 to drive the Austrians out of North Italy and form a federation under the Duke of Modena, they did not dream of including in it the whole peninsula or of creating an Italian nation.

They were almost as busy fomenting revolutions in France and Spain as in regenerating their own country. France, indeed, they never left at peace. Secret societies were busy simultaneously in Russia, in Greece, in Ireland, and even in the Swiss republic.

In 1821 the Italian revolutionist, General Pepe, founded at Madrid ‘an international secret society of the advanced political reformers of ail the European states.’

And from Spain he carried the organization into Portugal and France.

Mazzini made a much more effective union of the revolutionary elements in 1834 when, with the aid of Italian, Polish, and German refugees, he founded at Berne the society of Young Europe.

The organisation of Young Germany, Young Poland, and Young Switzerland dates from the same time and place, and Switzerland became the centre of all the agitations of the Continent.

Many of these and similar associations professed an excellent object. The Tugendbund, for instance, founded by the Prussian Prime Minister Stein in 1807, originally aimed at the deliverance of Germany from the foreign yoke imposed by Napoleon I.

Young Poland captivated the noble, the ardent, and the patriotic. The Carbonari had an alluring watchword in the Independence of Italy.

Opposition to Catholic and Christian Civilisation

But there was an ulterior purpose known only to the initiated, and perhaps not always contemplated even by them at the beginning of their enterprise.

That purpose the bond which united all the leaders of the conspiracy from the Irish Sea to the Grecian Archipelago, from Gibraltar to Nova Zembla was the establishment everywhere of an atheistic democracy. Kings and priests were equally hateful to the ‘Illuminated.’

There was to be no recognition of God in their republic.

They were hostile not only to the Catholic Church as an organisation but to Christianity as a moral influence. Illuminism sounded as early as 1777 the key-note of the whole movement.

Findel, the Masonic historian of Freemasonry, declares that ‘the most decisive agent ‘ in giving the order a political and anti-religious character was:

That intellectual movement known under the name of English deism, which boldly rejected all revelation and all religious dogmas, and under the victorious banner of reason and criticism broke down all barriers in its path.’

But Weishaupt found still too much ‘ political and religious prejudice ‘ remaining in the Freemasons, and consequently devised a system which, as he expressed it, would ‘ attract Christians of every communion and gradually free them from all religious prejudices. *

The ‘illumination ‘ of the brethren was to be accomplished by a course of gradual education in which Christianity was carefully ignored.

It was only in the higher degrees that the initiated were taught that the full of man meant nothing but the subjection of the individual to civil society; that ‘illumination ‘ consisted in getting rid of all governments; and that:

The secret associations were gradually and silent ly to possess themselves of the government cf the states, making use for this purpose of the means which the wicked use for attaining their base ends.’

We quote this from the discourse read at initiation into one of the higher degrees, and discovered when the papers of the fraternity were seized by the Elector of Bavaria in 1785. The same document continues:

Princes and priests are in particular the wicked whose hands we must tie up by means of these associations, if we cannot wipe them out altogether.

Patriotism was defined as a narrow-minded prejudice; and, finally, the illuminated man was taught that everything is material, that religion has no foundation, that all nations must be brought back, either by peaceable means or by force, to their pristine condition of unrestricted liberty, for ‘all subordination must vanish from the face of the earth.’

The ceremonies of initiation into the lodges of the Carbonari remind us strongly of this explanation of the principles of Illuminism.

The recruit was taught the same doctrine in both: that man had every where fallen into the hands of oppressors, whose authority it was the mission of the enlightened to cast off.

Here, however, as in the earlier society, the pagan character of the proposed new life was only revealed by degrees to those who were prepared for it.

The conspirators seem to have accommodated their system of education to the peculiarities of national training and disposition.

For example, they humored the religious tendencies of the Italians by retaining the name of God and the image of the crucifix in the ceremonial of the lower degrees, and even published a forged bull, in the name of Pope Pius VII, approving the Carbonari; while in the training of Young Germany just a contrary course was adopted.

‘We are obliged to treat new-comers very cautiously,’ says a report from a propagandist committee established among the Germans in Switzerland, ‘to bring them step by step into the right road, and the principal thing in this respect is to show them that religion is nothing but a pile of rubbish.’

Just so when Carbonarism was introduced into France: the religious phraseology and ceremonies which had been grafted upon its ritual for the satisfaction of Italian neophytes did not harmonize with French ideas, and all Catholic expressions were consequently expunged from French copies of the statutes.

Indeed, the rampant atheism of the secret societies of Germany and France has always been notorious.

Of the horrible manifestations of impiety among the higher degrees in Italy I hesitate to speak, lest I be accused of sensational exag geration.

Most of what I have thus far said of the principles and practices of the Carbonari and the Illuminati is quoted from their own authorities, and may be found in the work of their apologist, Thomas Frost (The Secret Societies of the European Revolution, 1776-1876. By Thomas Frost. London 1876).

For a more startling picture of their inner mysteries, the reader is referred to Father Bresciant who lived in Rome in 1848 and had direct testimony of facts which almost defy belief.

Mr. Frost, however, gives a glimpse of the worse than pagan spirit of Carbonarism when he describes the initiation into the second degree a ceremony wherein the candidate, crowned with thorns and bearing a cross, personated our divine Lord, and knelt to ask pardon of Pilate, Caiphas, and Herod, represented by the grand master and two assistants, the pardon being granted at the intercession of the assembled Carbonari!

In all the societies an abstract morality was taught which was not the morality of Jesus Christ, and laws were laid down at variance with the laws of the state.

Indeed, the members were carefully taught, by direct precept and by still more effective insinua tion, that the supreme authority for them, above the secular power and above the Church, was the lodge.

The society sought to detach them completely from the state by means of a code of laws distinct in form, and they were even forbidden to refer cases of litigation to the ordinary tribunals until they had been brought before the grand lodge, and reasons assigned for permitting a further investigation in a ‘pagan court.

Oath of Initiation and Penalties

But the chief agency which separated the assnciates from the outside world was the dagger. In the oath of initiation the newly-admitted member was required to invoke the most terrible penalties upon his own head if he violated his pledges to the order, and what those penalties were may be seen from the following articles of the secret statutes:

Members who disobey the orders of this secret society, and they who unveil its mysteries, shall be poignarded without remission.

The secret tribunal shall pronounce sentence by designating one or two associates for its immediate execution.

The associate who shall refurc to execute the sentence pronounced shall be deemed a perjurer, and a:} such put to death on the spot.

If the condemned victim try to escape by flight, he shall be pursued everywhere without delay, and struck by an invisible hand, even though he should fly for refuge to the bosom of his mother or to the tabernacle of Christ.

Each secret tribunal shall be competent not only to judge guilty members of the society, but also to put to death all the persons whom it may devote to death.

Such was the terrible hidden agency which promoted the revolutions of the whole continent during the first half of the present century.

The ‘True Esoteric Doctrine of Many’

I have said that it was only in the work of destruction, in hostility to the Christian religion and to social order, that the affiliated societies had their bond of union. Unity and Independence became after a while the cry by which they deceived the Italian people.

But they were quite as active in France and Spain, where national unity was always secure, and in Switzerland, where popular rights were guaranteed by republican institutions, as in Italy, where petty states were governed by absolute princes and Austrian armies.

And if there had been any doubt as to their ultimate purposes, that doubt must have been dispelled by their course during the past few years. The secret societies are now plotting as desperately against United Italy as they plotted before 1870, against the governments of divided Italy.

Mazzini never pretended that their work was done when a king was set up in the Pope's palace. He died conspiring against Victor Emmanuel and urging Italy to press on to ‘the goal of the revolution.’

The anniversary of his death was celebrated in March, 1877, by democratic demonstrations all over Italy, which the government was unable to suppress; the speakers at these meetings declared the commemorative ceremonies to be not merely a token of remembrance but a ‘promise,’ and they referred openly to a time for action ‘which was yet to come; while simultaneously a seditious circular, claiming for the Carbonari the right ‘to indicate and open the way to the kingdom of liberty, to the triumph of justice, to social amelioration upon earth,’ was distributed among the ranks of the Italian army.

A few days later several bands of Internationalists raised a revolt near Naples; and on the person of one of the conspirators arrested at that time was found the following declaration of principles:

INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF WORKING-MEN.

FEDERATION OF ROME AND LATIUM.

CLUB OF THE ROMAN SOCIALIST PROPAGANDA.

The club of the Roman Socialist Propaganda, accepting the general statutes of the International Association of Working-men as the rule of conduct which the proletariat must observe for its complete emancipation, estab lishes the following principles, which will constitute its revolutionary programme :

In the first place, the said club wishes the supernatural removed from all the ties of life, as it tolerates no tyranny, either human or divine. Nevertheless, it has no intention of imposing atheist principles on the consciences of the members. It declares that it respects in the members themselves any religious principle whatever which they may cherish.

It reserves to itself the right to combat superstition and error everywhere, confident that the development of science and instruction in the working- classes will destroy all idea of the supernatural, or of religion which betrays itself under any form of worship.

Nevertheless, since the society of the future which it undertakes to found must consist only of producers, and since from this follows the disappearance of all consumers who are not producers.it denies emphatically the right of any one to make capital or to speculate on the belief of others.

As for individual property, the said club, considering that the source and first cause of misery, of degradation, of servitude among the working-classes is precisely the accumulation in the hands of a few of the primary instruments and material of labour, declares it to be, on these grounds, supremely necessary for the emancipation of the working-men to destroy this accumulation in all its manifestations.

Moreover, recognising on the other hand that collective property, and hence the collectivism of the instruments of labor and production, are the only means for the total emancipation of the proletariat, the said club proposes to fight with all its strength, moral and material, for the destruction of individual property, and for the triumph and constitution of collectivism.

And since it recognizes that under the name of the state is summed up the first cause of the slavery of the human race, and since the state can only have in view, under whatever complexion it mayb,e presented, the main tenance of the existing economic and social privileges the said club declares itself, on these grounds, in favor of true anarchy as the negation of all power whatever which is imposed from high to low, or vice versa.

Denying the supernatural and denying the state, it follows as a necessary consequence that the club makes it its business to destroy the actual legal family, there not being in the future any other hereditary duty than that of working with all energy for the development of science and industry, and there being no recognition among the men of the future of any other tie than that of mutual as sistance and of the natural and brotherly affection which nature imposes upon man.

Further, and as a logical consequence of the above reasoning, recognizing as the basis of justice and morality that all religious and social ties whatever must give way to the full liberty of union between man and woman, the said club declares in favor of this latter, knowing as it does that man as well as woman has the full right of free union without the intervention of any othe: in this purely personal act.

However, as complete justice ought to be the foundation of the society of the future, the club recognizes that such union ought to be founded on reciprocal affection, esteem, and respect. Moreover, the said club desires that the society of the future should exercise surveillance over such union, in order that the rights of woman, as of man, be not prejudiced by any caprice whatever.

Furthermore, the club recognizes in male and female the duty to rear and educate children always under the surveillance of the society, as long as these are not in a fit state to be taken as children of the society itself, to be thereafter trained and disciplined in the several institutions, and finally sent to those trades and arts which they shall freely select without pressure on the part of any one.

It denies, however, any mastership by parents over children, recognizing these as children of society, to which they shall be bound by special duties and rights.

On this basis the Roman Socialist Club declares that it will co-operate with all its might for the foundation of the social organism of the future as that which it recog nizes to be the genuine bulwark of morality, of equality, and of justice.’

Undoubtedly these destructive and atheistic principles were not held by a large proportion of the revolutionary party in any country, but they constituted the true esoteric doctrine of many of the secret societies, and whenever the revolt gained a temporary success they were sure to manifest themselves and to shape the course of the insurgents.

Europe Awash in Revolution

[caption id="attachment_13088" align="alignright" width="382"] Statue of Pope Gregory XVI - predecessor to Pius IX[/caption]

Statue of Pope Gregory XVI - predecessor to Pius IX[/caption]

During the first half of the century the outbreaks were almost incessant. France lived in perpetual alarm. Every capital in Germany was in nightly danger of the dagger, the torch, and the barricade.

Italy was a wretched and distracted land of conspiracies and assassinations, suspicious princes and iron laws.

And in whatever foreign country the standard of local revolt might be raised, at once the beacon-lights of rebellion seemed to flash from the Italian hills. The Spanish insurrection in 1820 was the signal for a rising at Naples.

The French Revolution of 1830 inspired the outbreak in the Romagna.

The weak and uneasy states of Italy became a standing menace to all the absolute governments of the continent; and Austria in particular, mistress of Loinbardy and Venice, made it her ungrateful part to keep the whole peninsula in subjection.

It was Mazzini who first perceived that the secret societies, defeated in all their isolated attempts at revolution by this stem and formidable power at the north, must change their policy, drop the old methods of conspiracy for a while, cultivate the popular aspirations for independence, and concentrate their energies upon the ejection of the foreigner and the consolidation of all the Italian states.

The fate of pope and priests, kings and princes, could be settled afterwards.

It was with this view that he organized at Marseilles, in 1831, the Society of Young Italy, whose watchword, Union and Independence, captivated at once the generous, the ardent, the impulsive, the ambitious, and brought to the same work poetry, patriotism, and religion, the pistol, the dagger, and the poisoned cup.

What was to be done with Italy when it was united and rid of the Austrians was one of the secrets of the initiated never explained to the common people. But remarkable illustrations of the inner character of the movement were found in 1844 among certain papers seized by the police in Rome.

‘Our watchword,’ wrote one of the leaders:

must be Religion, Union, Independence. As for the King of Sardinia, we should seek some favorable opportunity to poignard him. I recommend the same course to be pursued in regard to the King of Naples. The Lombards may second our efforts by poison, or by insurrection against the Germans, after the example of * The Sicilian Vespers. Function aries or private citizens who show a hostile spirit must be put to death. Let them be arrested quietly during the night, and the report be circulated that they have been exiled or sent to prison, or have absconded.’

The conspirator Ricciardi wrote:

Independence can only be acquired by revolution and war; we must put aside all considerations founded on the progress of knowledge, civilization, industry, the increase of wealth, and public prospe rity. . . . The fatal plant, born in Judea, has only reached this high point of growth and vigor because it was watered with waves of blood. . . . Soon a new era will begin for men the glorious era of a redemption quite different from that announced by Christ.’

And Mazzini himself a little later, in an address to Young Italy, gave a significant explanation of his scheme:

In great countries it is by the people that we must seek regeneration; in yours it is by the princes. Get them on your side. Attack their vanity. Let them march at the head, if they will, so long as they march your way. Few will go to the end.

The essential thing is not to let them know the goal of the revolution. They must never see more than one step at a time. Profit by the least concession to assemble the masses, if it be only to testify gratitude. Fetes, songs, assemblies, relations established between men of different opinions, stimulate the growth of ideas, give the people a feeling of strength, and make them exacting.

You must manage the clergy, because the people believe in it; already it holds half the doctrine of socialism, for, like us, it has the sentiment of fraternity, which it calls chanty. and habits make it the imp of authority that is, of despotism. We must take what it has of good and leave the bad. Try to make equality penetrate the Church, and all will go well. Associate! Associate!Associate! Everything is in this one word.

Secret societies confer an irresistible force on the party which can avail itself of them. When a large number of associates, receiving the countersign to spread a certain idea and to make it public opinion, shall be able to concert a movement, they will find the old structure riddled in every part and ready to fall as if by a miracle at the first breath of progress.

They will be astonished themselves to see kings and princes, the priests and the rich, who formed the ancient social edifice, flying before the sole power of opinion. Courage, then, and perseverance.

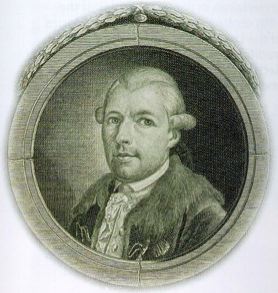

Vincenzo Gioberti - Priest and Philosopher

[caption id="" align="alignleft" width="360"] Vincenzo Gioberti 1801-1852[/caption]

Vincenzo Gioberti 1801-1852[/caption]

In the prosecution of this new scheme of revolution the conspirators obtained invaluable help from a most unexpected ally.

The erring genius of the brilliant, learned, but unfortunate priest and philosopher, Vincenzo Gioberti, did more for them than the machinations of the lodges.

Carried away by visions of a new Italy and a new Catholicism, he forgot the divine mission of the Church in speculations as to what she might accomplish in purely secular enterpiises.

His great error was in thinking of religion as an agent of civilization rather than an instrumentality for saving souls.

And thus he was led into the blunder of attempting to unite God and the world in an equal partnership.

He conceived the idea of an Italian federation with the King of Sardinia as military head and the Pope as spiritual president: a sort of dual empire like that of Japan, with a tycoon at Turin, a mikado at the Vatican.

He affirmed that the clergy had failed to recognize the progress of civil and social culture and had therefore lost its influence over the human mind.

Nations had reached their majority and could no longer be held in tutelage.

The priests must give up a dominion incompatible with modern civilization, throw themselves into the front of the new social movements, and, hand-in hand with the political agitators, lead Italy to a material glory such as no nation on earth had ever seen.

His book, Del Pimato morale e civile degli Italiani, was welcomed with unbounded enthusiasm. The charm of a glowing style, the force of an original, cultivated, and poetic mind, the glamour of a philosophy which seemed to meet the wants of an exciting and uneasy time, turned the heads of the whole nation.

Gioberti, Cesare Balbo, Massimo d Azeglio, were the creators of a new literature, and Italy read them with flashing eyes and quicken impulse.

Theirs was a reform which seized upon the fancy of good and bad alike, and hurried into a common delusion the heedless Christian and the veteran Carbonari, the young, the imaginative, the adventurous, and the artful.

Mazzini, who after wards became one of Gioberti's bitterest enemies, was too shrewd to undervalue this influence. He sought an interview with Gioberti in Paris; he offered terms of co-operation.

He even went through the form of renouncing what he styled his own ‘more narrow views,’ and suggested a National Association which, adjourning all questions of forms and spirit of government, faith or scepticism, God or the devil, should unite Italy in the single purpose of creating an Italian nation.

Different as the aims of the two men were for Gioberti included even the Austrian government of Lombardy and Venice in his proposed union they embraced each other for the moment.

Together they swept the peninsula. Every city from Palermo to Milan was aflame with the new ideas. The soberest patriots lost their composure, and some of the clergy began to dream wild dreams of political change, and to see visions of reformed conspirators kneeling at the feet of a democratic pope.

We look back upon those days from the vantage-ground of experience, and we wonder that men should have been so deceived.

But 1848 had not then given the lie to the professions of 1846.

Devout Italians at that time did not see that the secret societies which assailed the Church on one side of the Alps with fire and sword could not be sincere in offering to place it in a new position of power and glory on the other.

Such was the moral and political ferment which agitated Italy during the last days of Gregory XVI. That much-maligned Pope spent the whole fifteen years of his reign in violent efforts to keep back the threatened explosion.

Whether any policy that lay within his choice would have sufficed to set to rights such evil times may be doubted.

The policy of strict repression, at any rate, did not, and at the beginning of the year 1846 a catastrophe appeared to be inevitable. Perhaps it was the age and infirmaries of the Pontiff, after all, that postponed the outbreak. He was plainly nearing his end; and the leaders of Young Italy preferred to wait.

Buying Books at Amazon Through These Links Gives Us a Commission. This Supports Our Apostolate. Thank You if You Can Help Us Like This!

Comments

comments are currently closed

7 responses to “Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 2: The Carbonari and Other Secret Societies”

[…] Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 2: The Carbonari and Other Secret Societies […]

[…] Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 2: The Carbonari and Other Secret Societies […]

[…] « Feast of St. Brigid in Ireland Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 2: The Carbonari and Other Secret Societies » […]

[…] « Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 2: The Carbonari and Other Secret Societies Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 4: Conspiracy, War and Revolution » […]

[…] Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 2: The Carbonari and Other Secret Societies […]

[…] Life of Pope Pius IX – Ch 2: The Carbonari and Other Secret Societies […]

[…] by the mid-1800s, the Church in Europe was beset with countless problems. Revolutions, fomented by secret societies, were attacking the old structures of Christendom […]