Problems beset me as I begin this review.

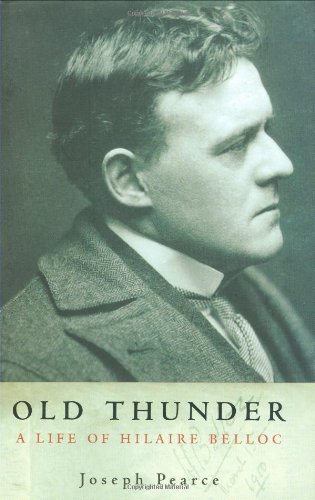

For example, I might say this is a delightful and amiable biography about Belloc – which indeed it is.

But there is a difficulty with such. For the subject of the book – Hilaire Belloc, the man himself – was not simply delightful and amiable.

No, Belloc was also deadly serious.

And it is this profoundly serious side to Belloc that seemed strangely lost to me, reading Pearce’s otherwise rich, well-written, well-researched book.

Still, this was tough, because this was the very thing I sought, as I began consuming one Belloc book after another. I wanted to understand who this pained, passionate man was.

And I could not help but feel a certain disconnect between the man whose books I devoured – and Pearce’s story of his life.

In other words, ‘my’ Belloc and ‘Pearce’s’ Belloc often seemed like two different men. Yet Joseph Pearce clearly devoted a lot of time, love and dedicated research to this invaluable biography.

What was I missing?

‘My’ Belloc – Solemn, Passionate, Radical

Perhaps it is best if I begin articulating ‘my’ Belloc.

Clearly, Belloc was an author with a grim vision of the world he lived in – a world he saw ravaged by Capitalism and Communism alike. He was also a man vitally concerned with how Christianity was being destroyed by modern materialistic theory.

We will shortly consider this latter, ‘theological’ Belloc – a soul earnestly occupied with the menace to the Faith. But let us begin with Belloc, the economic and social thinker.

Here was a man who not only deeply commiserated with the poor, being crushed by a rich plutocracy, but who also confronted the horror of Communism – and the millions it exterminated. (And yet Communism, he saw, was, in the end, only a fatal reaction to Capitalism.)

And so Belloc preached Distributism as an alternative to Capitalism and Socialism. Distributism meant to foster the widest distribution of property possible. It intended, then, on justice for the little man and small business. It also hoped to protect the natural beauty of the rural life in a way that makes Belloc a forerunner of the Green movement today.

Now, Belloc’s Green distributist vision would have relied on massive regulation of business and high corporate taxes to be effective. (For example, under Belloc’s vision there would be small farms – not agribusiness. None of the huge chain or department stores we see today would exist – because they would be taxed or regulated out of existence.)

Needless to say, none of this made him popular in a society as profoundly capitalist as the British Empire.

But Belloc’s radicalism did not stop here. Belloc preached a staunch, uncompromising Catholicism in a still very anti-Catholic England. Indeed, Belloc blamed Anglo-American Capitalism on the Reformation; he saw how Catholic cultures had never succumbed to Capitalism to the same degree as the Anglo-Protestant sphere.

New book from Roger Buck, co-author of this site. Click here to buy!

All this is to say: The man had guts. The man had a radical vision, spread out over a career than spans an astonishing 153 books (not to mention beautiful poetry, time spent as a national politician and journalist – and much else besides.)

Reading Belloc, I see a man with great (Oxford) education and intellectual acuity – especially compared with our ‘dumbed-down’ Twenty-First Century. I see a soul wrought with pain, trying to address the tragedy of the West. I see a thinker with courageous, unpopular views, which isolated him from the rest of the English society he lived in.

Indeed, one thing Pearce’s biography reveals is how well-known Belloc became in his day. Belloc was either publicly admired or abhorred by a host of great British literary figures of the age. All manner of literati made both very vocal approbations and condemnations, including Evelyn Waugh, H.G. Wells, George Bernard Shaw and Virginia Woolf.

On the admiring side, many of these folk followed Belloc into the Church: G.K. Chesterton was one, of course, but I was surprised to see how many more there were, including Siegfried Sassoon.

Sir Herbert James Gunn once gave a sketch of Belloc (and Chesterton) to the future Queen Elizabeth, who expressed her delight, saying she would hang it in her quarters. Although this is probably nothing more than royal protocol, it nevertheless reveals Belloc’s cultural impact. He was also welcomed in private audiences with both Popes and political leaders – including President Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

One cannot imagine any deeply traditional Catholic, as Belloc was, having such impact in British and American life today …

These days, G.K. Chesterton is remembered more than Belloc. But Pearce reveals the extent to which Belloc inspired Chesterton. Not only was Belloc instrumental in Chesterton’s conversion – to say the least – but he influenced him profoundly in other ways. As Pearce notes:

Chesterton … openly declared himself a disciple of Belloc as far as their shared advocacy of the political philosophy of Distributism was concerned. ‘You were the founder and father of this mission; we were the converts but you were the missionary’ he wrote in an ‘Open Letter’ to Belloc.

All this testifies to a remarkable, powerful spirit driving Belloc. It is a bold spirit, born of the burning gravitas he possessed. And it is this burning gravitas, I suppose, that best characterises ‘my’ Belloc.

‘Pearce’s’ Belloc?

But coming back to Pearce’s biography, here was the odd thing. I could no longer feel that same gravitas, as when I read the man himself. Now, Pearce regularly speaks of Belloc’s ‘genius’ – but I could not help but feel he fails to capture what makes for authentic genius – the profound spiritual life.

Now, Belloc had other sides of his character, to be sure. He was famously garrulous and noted for the conviviality he shared with men like people such as G.K. Chesterton.

And Pearce captures that side of Belloc very well indeed. There is indeed much that is delightful in his colourful tales of Belloc dazzling Oxford, drinking ale with his friends in his beloved Sussex or tramping around Europe, America and Africa.

Moreover, a particularly beautiful thing that Pearce uncovers is Belloc’s childhood religiosity. As he notes, the young Hilaire Belloc possessed:

A piety that was surely unusual in boys of his age. He also appeared to have inklings of mystical theology beyond that which one would expect of a boy who was not yet thirteen. Commenting in a letter to his mother of how he found it easier to ‘pray beautifully’ on days when the school chapel was ‘all a beautiful grey’ in the evening light, and when ‘the sanctuary lamp looks so bright and yet lights up so small a space’, he expounded on the ‘essence of God’ in beauty and love:

I think that beauty and love, and things which people generally look down upon as not stoic or heroic, are the essence of heroism and manly feeling, and this because they are the essence of God as we hear of Him and understand Him. I felt this in chapel today, that the light feeling which proceeds from love or something beautiful, is not a feeling that will pass, but the happiness of angels in the love of God.

Have you ever felt that in one of those beautiful churches, Notre Dame of St Ouen, how one loves the beauty around one so much that one is convinced that it was the grace of God, as well as man, who helped to build that church?

Pearce also captures the personal tragedy that haunted Belloc’s life – losing a deeply beloved wife at an early age, losing two sons in war and suffering a debilitated old age. But personal pain is one thing and pain for the world is quite another.

Pain for the world: This is partly, I think, what I found missing in this book. For this, I think, must be part at least of Belloc’s passion. At least part, but there must be still more.

What really drove Belloc? What drove this radical Catholic distributist vision that made such an impact on the Protestant Anglosphere? After reading Pearce (almost twice, in fact) I am still hunting answers.

Belloc’s Obsessions?

To be fair to Pearce, my difficulty is not limited to him alone. A similar problem besets numerous commentators on Belloc – even sympathetic ones. Now, these clearly include Pearce’s sources – as I found when I began reading older memoirs and commentaries on Belloc and his work.

For hunting Belloc’s soul, I kept turning to the same source material for Pearce’s biography. There I found a recurrent theme – one which strikes me as dismissive. For example, one old writer, otherwise sympathetic, complained of Belloc’s ‘pet theories’.

Pet theories – it is a way of sneering at Belloc’s radicalism, sneering because (I cannot help but suspect) Belloc refused to conform to comfortable English bourgeois values.

People could appreciate Belloc – but when he stepped outside their comfort zone, they derided his so-called ‘pet theories’.

To my mind, Pearce occasionally succumbs to the same tone. He talks, for example, of Belloc's ‘fixation on questions of history’ - but employing such pejoratives arguably misses the point of the entire raison d'être for Belloc's work as a historian.

Similarly, Pearce criticises his 'theological and historical obsessions'. The latter point comes when Pearce invokes Belloc's horror of Calvinism and his feeling that Calvinism permeated the writing of the Bronte sisters. Pearce would seem to write this off as ‘obsession’, just as earlier generations wrote off Belloc's ‘pet theories’ …

It is as if there is a ‘received wisdom’ about Belloc, passed down from one generation to the next. Belloc had his ‘pet theories’, his obsessions ... It is a ‘wisdom’ which tries to subtly discredit the man by a society - largely English, capitalist and Protestant - that was highly uncomfortable with Belloc.

When Pearce would appear to dismiss Belloc's criticism of the Brontes, one may wonder if the real problem is this: The Brontes are unassailable paragons of English literature. If Belloc chooses to assail them on the grounds of Calvinism, well ‘tut, tut, old man’, it must be that obsession of yours.

It is as though it is self-evidently crankish to critique the great Brontes like this. I wonder, I wonder. I myself do not know the Brontes. I do think, however, that Belloc's heart was bleeding in ways few people will ever understand.

As a historian, he knew - more importantly felt - the dark sides of Calvin's legacy, like few of us can today. His pained, passionate heart was the font of his genius, as Pearce puts it. But if Belloc was possessed of genius - as Pearce regularly writes - is it not possible his so-called 'theological and historical obsessions' are indebted to that genius?

Reading Old Thunder, I wonder whether Pearce has ever wrestled with this question: Could it be the Brontes actually are Calvinistic in some sense of that word? Could it be that he is passing on an ‘old, received wisdom’ regarding Belloc's ‘pet theories’?

None of this is to say that Belloc's thinking is beyond reproach! He was flawed, fallible, blinded - fallen like the best of men are, in any age. We come to this below. My point is simply that the real Belloc may be obscured by the accumulated clichés around him. And someone as radical as Belloc will inevitably accumulate antagonistic interpretations ...

Against the Modern World

In writing this, I am reminded of words I once published at this website, courtesy of Paul Kingsnorth.

Kingsnorth is, in certain limited respects, like a modern, secular version of Belloc. He is an Englishman with a love of English rural life and tradition that is being destroyed by modern capitalism. Both are men against the modern world.

Now, Kingsnorth never makes Belloc's connections, as far as I know, between Capitalism and the loss of Catholicism. Yet he represents, it seems to me, a moral vision which very much attracts the same kind of opprobrium Belloc once suffered. As Kingsnorth writes:

Any positive evaluation of the past, and any analysis emphasising continuity over change is branded as indicative of reactionary politics, emotional regression, or both: an irrational scramble for shelter from the vagaries of the modern world.

Yes, men like Belloc or Kingsnorth are branded. Even if Kingsnorth suffers none of the anti-Catholic stigma that Belloc did, the branding still goes on. Kingsnorth describes it thus:

You are a nimby, a reactionary and a Romantic idiot. You want to go back to a Golden Age, in which you can play at living in prettified village poverty because you have never experienced the real thing. You are a privileged, bourgeois escapist. You dream of a prelapsarian rural idyll, because you can’t cope with the modern multicultural, urban reality.

You are a hypocrite. You are personally responsible for the misery of a lot of poor people in Africa who need you to buy their beans. You need to get real. This is the Twenty First century, and there is business to be done. There is poverty to eliminate, an economy to expand, a planet to be saved. You are not helping by playing at being William Cobbett or William Morris. Snap out of it. Grow up.

These are some of the things you can expect people to say to you if you dare to talk, today, about the land.

Specifically, if you are foolish enough to suggest that there may be anything positive about rural life, about working the land ... or about the possibly simpler or more essential life it may represent, you can expect to call down a firestorm upon your unsuspecting head.

Yes, Belloc was a clear predecessor for Kingsnorth's moral concern here. But, as we say, he was also radical about much, much else besides. Radical: It is from the Latin radix meaning root. Kingsnorth, I think, wants change without going to the root of the problem. For Belloc, the root of the problem lay in a secular materialistic society that was, in its turn, rooted in the Reformation's devastation of the Sacramental Church. All this was sufficient to ensure that the ‘firestorm’ called down upon Belloc's ‘unsuspecting head’ was probably beyond anything Kingsnorth has ever imagined.

Legitimate Criticism of Belloc

All this is hardly to say everything Belloc said or did was beyond criticism! Belloc, as we have said, was a man of passionate conviction. Passion cuts both ways. Without his passion, Belloc would not have had the impact he did.

Yet, by the same token, Belloc was, no doubt, excessive at times - as all men of passion are liable to be. An excess of passion, however, is not the same as obsession. I object to objections of Belloc as obsessed - as I do to talk about ‘pet theories’ by genteel folk who do not care about the world like Belloc obviously did.

However, it does not follow - ipso facto - that I think Belloc is pure and unproblematic. There are undoubtedly serious problems with Belloc's extensive, complex legacy. Some of these stemmed from his conviction, in old age, that parliamentary democracy was anything but democratic. To his credit, Belloc had actually been twice elected to parliament (as a radical Liberal MP - which is to say on the left wing of the major party of the Left at the time.) That experience would disillusion him forever. He became convinced British society was not the real democracy he yearned for - but rather controlled by a plutocracy.

Still, his bitter experience of the sham nature of parliamentary democracy led him, later on in life, to highly questionable attitudes. Tragically, both Belloc and Chesterton, for example, spoke of Mussolini approvingly - at least early on. Clearly, they hoped Mussolini might offer protection from both the Capitalists and the Communists. What Pearce writes of Chesterton would seem likewise applicable to Belloc:

Chesterton was nonetheless insistent that his discussion of the political situation in Italy should not ‘be mistaken for a defence of fascism’ ... In spite of this, he still felt that Mussolini's fascist syndicalism was preferable to the institutionalised plutocracy of multinational capitalism or to the dictatorship of the proletariat [in]Bolshevik Russia.

Yes, whilst Belloc deplored Hitler from the start, he seems to have been gulled - somewhat at least - by the early Mussolini.

There is an even more serious matter regarding Belloc's alleged anti-semitism. It is a matter we will explore at this weblog at some point. I still need to ponder it, in fact, much more deeply myself.

For the moment, let us clearly state that Belloc's attitudes were not anti-semitic. They had nothing to do with racism - perceiving inferiority through the blood.

Rather, a certain - albeit limited - parallel to Belloc's view might be found with the way certain Europeans are anti-American today. I once knew a European who regretted his personal necessity of flying to America - because he did not want to yield a single tourist penny to a system he perceived as war-mongering and ruthlessly capitalist. I thought this was overblown indeed, given that Europe is far - very far! - from innocence in these matters.

Belloc perceived Jewish groups as complicit in both the capitalist plutocracy he detested, as well as the Bolshevik revolution (amongst other revolutions). This led him - like so many others, prior to the Third Reich - to deplorable statements at times (particularly when taken out of context).

Today, the true Christian heart can do nothing but weep for anything - any remark, any piece of writing - that fostered the climate in Europe which led to the unspeakable horror of the Shoah.

Belloc may have said terrible things on occasion regarding Jewish people, but they had nothing to do with an ‘inferior race’ to be suppressed or exterminated, anymore than anti-American Europeans believe Americans belong to an inferior people.

The tragedy, the horror here is a matter of (perceived) ideology and attitudes - not racism.

It is to Joseph Pearce's credit that he illumines this highly-problematic aspect of Belloc's legacy - and neither ducks it, nor succumbs to the illusion that Belloc was anti-semite. He reveals, for example, how mild Belloc was compared to the much of the mainstream of the day.

For example, he quotes both Winston Churchill and The Times of London as being considerably less moderate than Belloc on this topic. And he shows how Belloc chillingly predicted, in the 1920s, renewed Jewish persecution with deep concern that this should never happen.

Helpfully, Pearce also quotes Belloc himself on the matter:

There is not in the whole mass of my written books and articles, there is not in any one of my lectures (many of which have been delivered to Jewish bodies by special request because of the great interest I have taken). there is not, I say, in any one of the great mass of writings and statements extending over twenty years, a single line in which a Jew has been attacked as a Jew or in which the vast majority of their race, suffering and poor has received, I will not say an insult from my pen or my tongue, but anything which could be construed even as dislike.

For myself, I trust that Belloc was a sincere, humane man and that these are sincere, humane words. Unfortunately, Belloc may have been unconscious of his words, at times - as the best of men are.

He also had an unfortunate habit of teasing, even taunting those he disagreed with: Protestants, scientific materialists, wealthy capitalists - and Jews.

But the first three groups never suffered the Shoah. The last did - and in this terrifying, unimaginable truth, we have cause to weep for anything Belloc, or anyone else, may have said which contributed in any way.

But I must stop with this. This is a book review and not a book! I include these notes on Belloc's shadow (as a Jungian would call it) or his fallen nature (as a Christian would call it) simply to say that I am not advocating - ipso facto - everything Hilaire Belloc ever said or did …

New book from Roger Buck, co-author of this site. Click here to buy!

Rescuing Belloc

And yet I am haunted, haunted by Hilaire Belloc. His true nature, his real legacy must be recovered.

Pearce makes a genuine contribution to this necessary task - for which I am truly thankful. Still, I cannot help but wish he had penetrated deeper.

We might conclude with this. Pearce writes beautifully when he describes the younger Belloc, the pious, even mystical child or the convivial, loquacious Belloc drinking ale with Chesterton.

We are also indebted for his portrait of the Irish-American Elodie Hogan who became Belloc's beloved wife.

Indeed, I think Elodie's immense contribution to Belloc's mission has not yet been sufficiently appreciated. And Pearce reveals how her profound Irish piety rescued Belloc's soul ...

But to my mind, Pearce falls short when dealing with the older, grimmer Belloc. And it is to this Belloc that we owe such great works as Survivals and New Arrivals - perhaps the most important I have yet read.

Pearce does not do sufficient justice, I think, to the fact that here was a man vitally concerned with nothing less than the death of Western Civilisation.

But years later, many of us can only feel Belloc was a prophet: for we appear to be staring the death of Western Civilisation in the face.

Yes, Hilaire Belloc was a prophet, seeing the West crushed by plutocratic capitalism on the one side, socialism on the other and everywhere a ‘dumbing down’ through a capitalist-controlled media.

Here was a non-complacent spirit suffering the agony of acute insight into the world drama - as it unfolded over centuries. But this spirit needs rescuing from the complacent commentaries of generations bent on trivialialising his thought.

This needs to be seen, I think, and Pearce's Old Thunder falls short of the mark in helping us to see it.

Ironically, what Pearce sometimes misses may be intimated in the very title of his book. Old Thunder - it was his mother's pet name for a small child born in 1870, just outside Paris.

For on the afternoon that Belloc was born, a mighty thunderstorm erupted in the French skies above his home.

His English mother soon took to calling the small boy ‘Old Thunder’.

But one might ask: Why not ‘Young Thunder’ - or even ‘Little Thunder’?

My guess is that Belloc's intense nature was apparent at a very early age; he was already old, old before his years ...

But perhaps I am being too harsh on Pearce. It cannot be an easy task to do real justice to a nature as profound, as complex and as multi-faceted as Hilaire Belloc's.

For whatever its limitations, the book has also rendered me real joy, extending fresh, rich insights. I have, as I said, nearly read it twice now and I can imagine myself turning to it, in one way or another, for the rest of my days, as I continue my quest for Belloc's soul.

/

Foreword for Monarchy by Roger Buck

Comments

comments are currently closed

6 responses to “On Old Thunder – Joseph Pearce’s Life of Hilaire Belloc (Review)”

[…] « On Old Thunder – Joseph Pearce’s Life of Hilaire Belloc (Review) […]

[…] We find fragments of a letter from her in Joseph Pearce’s biography of Hilaire Belloc: […]

Tragically, both Belloc and Chesterton, for example, spoke of Mussolini approvingly – at least early on. Clearly, they hoped Mussolini might offer protection from both the Capitalists and the Communists.

What is tragic about that?

“Today, the true Christian heart can do nothing but weep for anything – any remark, any piece of writing – that fostered the climate in Europe which led to the unspeakable horror of the Shoah.”

Even “I am fond of Jews, but oh, it’s funny when they lose”? Though that one was GKC.

Even statements in Rzycierz Niepokalanej (Knight of the Immaculate), a paper by Father Maximilian Kolbe OFM?

Even though the latter was “canonised” by a “Pope” who is himself “canonised” in 2014?

Did Belloc and these other ones really foster that climate? And did no writings of any Jews do so?

Quickly, Hans- Georg, I fully stand by what I wrote.

This is not to say that in the often terrible history of Jewish-Christian relations, there is not enough blame to go around on both sides.

Also saints and great men like GKC can make mistakes and yet still be saints and great men. But if Chesterton was rejoicing in others’ misfortune (?) here, it troubles me. Nonetheless I know GKC was very beautiful. Still, we are each of us fallen.

For me, it is the part of humility to recognise what we Catholics have been guilty of and need to do penance for.

I weep for the holocaust and really I am sure I do not know how to weep deeply enough.

There are very complex, terrible realities here and while it certainly doesn’t help that our new politically correct “though police” ban any any enquiry into these issues, I do weep and ask that God open my heart to weep even more …

As for Mussolini …

You are right there is nothing tragic in wanting to offer protection from Capitalists and Communists!

Belloc and Chesterton saw that need very clearly and our politically correct “thought police” would like to obscure their valid concerns about the evils of plutocracy and Marxism.

The plutocracy that controls our media is evil – this I know.

But both men saw through Mussolini in the end – thank God!

“But if Chesterton was rejoicing in others’ misfortune (?) here, it troubles me.”

The context was the Marconi case.

Jews were very well integrated in English society, indeed a bit too much into the House of Lords, if Belloc and Chesterton were right about it.

Some Jew had confused his public position with his’ fellow Jews’ private commercial interests, and FOR ONCE an English court had condemned a corrupt Jew.

Hence “it is funny when they lose”.

On the other side, it was very tragic when they won Palestine through Auschwitz – both in Auschwitz and in Palestine. But if they lose a court case for corruption again, I will not cry tears of blood over it, I will very much like to quote the full poem by GKC.

It also says “I am fond of Jews” – and he was since the school days, when a Jewish comrade actually admitted to having a family and being proud of it, contrary to the school ground mores of ignoring the fact one had one.

“But both men saw through Mussolini in the end – thank God!”

Neither of them was fooled by Mussolini, because when Benito came off as an anti-racist in the interview he gave the English Journalist GKC, he still was one. He swung over to racialism in 1938, with Carta della Razza -when GKC was already dead. Even so, GKC gave a reserved praise of Benito. And no praise at all for his usual English admirers, among whom Mosley and the cousin A. K. Chesterton.

Both liked the fact that though Journalists were more muzzled about government, they were, unlike England, unmuzzled about Freemasons. This however more written in GKC, in the relevant chapter of Eternal Rome. Both liked the fact that corporations were given official status and comprised both employers and employees. Belloc thought that Distributism could take care of itself without becoming a Servile State via farm monopoly in the countryside, but needed a Corporatist protection in the City branches of business. I can’t recall exactly where he wrote that, but I think it is true.

I also totally prefer electing according to proportionality of the voters’ professions, than proportionality of the voters’ preferences in party demagogues. Also because the professions are not classes, they cut across the division of rich and poor.

There was nothing to regret about having said that.

Ethiopia was another question. GKC was impressed, like the gentleman he was, that Ethiopians outside Italian rule were doing horrible things to women. I have heard that excision is not just North African Muslims, but also Ethiopians. I have heard about the Ethiopian custom of bride ravishing. Note, in 1943, Pius XII’s Rota discredited at least the latter excuse for Ethiopian venture, by saying that there was not enough evidence to prove such and such women were really forced to marry. In other words, Chesterton and those who considered “forced marriages” as “horrible things done to women” may have been fooled by appearances. Note also, in Ethiopia, Mussolini was not original as fascist, he was heir of Italian 19th C. liberalism.

I have seen papers of immigrants from Italy to Sweden, with women who left school after 5 or 3 or even 2 years. I think this is vastly preferrable and much less totalitarian than the West today enforcing school attendance up to age 16. Especially I think Bill Clinton in 1995 when hearing of a 12 year old girl who had quit school by marrying an old man was MUCH more totalitarian than Benito Mussolini about schools. As to limit of matrimonial age, the Italian 18/18 limit was also a bad heritage from 19th C. Liberal Kingdom of Italy.

I recently learned or learned again that I had lost a “quasi grandfather”. He was raised in the schools of Mussolini, while Istria was under Italian rule and retained a good impression of Il Duce.

I learned also very many years ago how, when the latter became a puppet of Hitler and started delivering Jews to camps, the Mayor of Assisi was endorsing the rescue campaign with very specific references to early Fascism not being antisemitic and also to Jews having done Fascism a good turn.

I think a Catholic SHOULD take some distance from régimes like Hitler or Ustashi, but apart from those two, I think most Fascisms were comparably good. Apart from Fascism, so was Christlich Soziale Union and partly Christ-Democratische Union (Franz Joseph Strauss and Conrad Adenauer), and of course Eamonn DeValera.

If you ask about the Military Junta of Argentina, I agree they were definitely NOT good, but they are less entitled to be considered Fascists than Peron. The Swedish Fascist movement Nysvenskarne retain references to both Mussolinis Carta del Lavoro and to Peron’s legislation about social relations between employers and employees. I would very much like the Nysvenskar, if they had not, like other Protestants, a certain Racist bent back then and ranging to Seventies. But the Swedish Social Democrats were the main culprits on that one.

I have no reason either to regret the words of GKC or Belloc or to exchange them for Mosley and AKC.