Before pronouncing something truly great, prudence demands caution. Whether it be a book, a poem, a symphony, or any other work of art, longer consideration—a certain test of time—is needed.

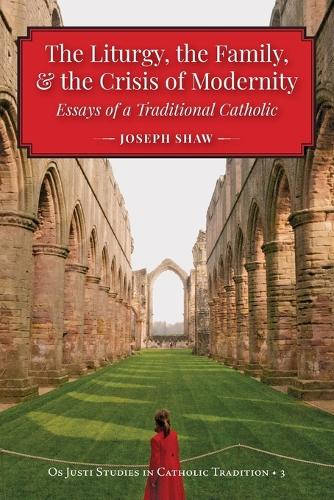

Closing the pages of Joseph Shaw’s first book, I needed to remind myself of this! For the temptation to over-hasty hyperbole was present, after finishing this wide-ranging set of essays entitled The Liturgy, the Family, and the Crisis of Modernity.

What can I say? I am moved, moved more deeply than I know how to say. I am startled, startled because although I expected a worthy, well-argued effort from Shaw—whose judiciousness and clarity of analysis have long impressed—I did not expect an impact like this.

Broadly speaking, the impact came on two fronts: both Shaw’s understanding of modernity’s crisis and his profound articulation of my only hope for this crisis—which is that the Catholic Church finds her way back to her true nature.

But let us begin with the first: the crisis. The excavation of the depths of sheer chaos, deepening chaos, of the modern world is truly remarkable. Now, conservatives and traditionalists have a well-known set of narratives to explain this calamity, which ranges from morality to epistemology, from the collapse of ethical standards to the despair of knowing whether anything is really true.

At least, the good books possess such accounts. Other books, alas, too easily descend into vilifying enemies as evil foes of the righteous, whether these be certain progressive politicians, sinister economic cabals, secret societies, or even ethnic groups.

I have read both sorts of books for twenty years at least. Picking up Shaw, I felt confident of a careful, nuanced narrative of the first type: an admirable examination of territory that is, nonetheless, familiar.

Again, though, I was startled. For after all these years, it is rare to find something as fresh, as thought-provoking, as original as the exploration of the crisis in these pages – one that marries acute, up-to-the-minute observation of unfolding secular trends with a striking inquest into the deep, underlying reasons for these trends (or rather tragedies).

To be clear, there is no overarching examination of the chaos here. As its title suggests, Shaw’s book is thematic rather than comprehensive and systematic. Only selected shards of the crisis – e.g. feminism, Freudianism, the castigation of custom, ritual and authority in favour of an often-manic search for ‘authenticity’, etc.—are held up to the light.

But what light! Depths of darkness are dispelled by a careful, original mind that has self-evidently sought for answers (no, thirsted for answers) over long years. Shaw is also bold, daring to go places where other conservative thinkers hesitate. Just how bad is patriarchy, Shaw asks, shunning the kind of reflexive concessions to feminism that too many of us indulge in without a moment’s thought.

And more in the book reveals a courageous refusal to kowtow to the automatic idols of the modern age. Then, there is the judicious tone throughout. Here is no frenzied, vitriolic quest to smash these idols to smithereens. Just question them, even gently question them. For God’s sake. For humanity’s sake. So that we are all not swept away in an unconscious confession to the Feminist Creed being unquestionably correct in everything it ever says of patriarchy …

But I began by saying I was impacted by more than just deconstructing of crisis. No, Shaw’s response to this crisis not only moves me, it also, as I shall come to, nourishes. Now, the book is subtitled Essays of a Traditional Catholic. No one should be surprised, then, that the solution offered here is a courageous, consistent commitment to the Faith, with particular emphasis on the Latin Mass, as capable of meeting deep spiritual needs that a modern rationalist liturgy fails to reach.

In other words, Shaw stands for a staunch Catholicism. Yet with a difference! Too much staunch Catholicism these days is marred by aggression, even viciousness. This is sadly understandable, inasmuch as traditionalists have long been treated like lepers. (As Shaw notes, even Joseph Ratzinger pointed this out as long ago as 2002!) Moreover, traditionalists register the sheer scale of the ecclesial catastrophe like few others.

Awake as they are, it is surely forgivable if their pained hearts sometimes react to those who remain comfortably numb, let alone those who actively seek to subvert and destroy.

Alas, though, aggression all too easily alienates. And here I mean not only extreme progressives in the Church, but also middle-of-the-road layfolk who might more easily listen to traditionalists, did they not sound so shrill.

No, Shaw proffers something decidedly un-shrill. His arguments are reasoned and fair-minded with, one may add, often brilliant philosophical precision and questioning (again with fairness) of the inherent contradictions and unquestioned assumptions at the heart of modernity.

But beyond all this is something more elusive, harder to capture in words. Perhaps there is no more apt adjective than the word rich. Now, Shaw’s new book is enriched by erudition and tradition, but I mean something still more by that term. That ‘more’, though, is, again, elusive. But certainly, it relates to the self-evident fruit in these pages of a man striving over years to live and think, really think, in committed, consistent conformity to Catholic faith and tradition. Such striving must yield integration and substance, and perhaps these, more than anything else, lie at the root of what so deeply nourishes me here.

At any rate, nourished I am. And I feel galvanised into further effort towards striving for the same—as the only real response I see to the grim, growing horror confronted in these pages.

Prudently, I wait before declaring this book a true great of our age. But that does not stop me feeling a certain greatness therein, still working in my heart after closing the pages.

Buying Books at Amazon Through These Links Gives Us a Commission. This Supports Our Apostolate. Thank You if You Can Help Us Like This!