Today is the feast of Lorcan Ua Tuathail, better known as Laurence O’Toole (1128-1180) principal Patron Saint of Dublin, Bishop and Confessor.

He was a Saint during a key and tragic stage in Irish history – the Norman invasion under King Henry II of England which laid the foundations for British domination of Ireland for the next seven hundred years.

He was also key figure in the reformation of Irish Catholicism in the Twelfth Century.

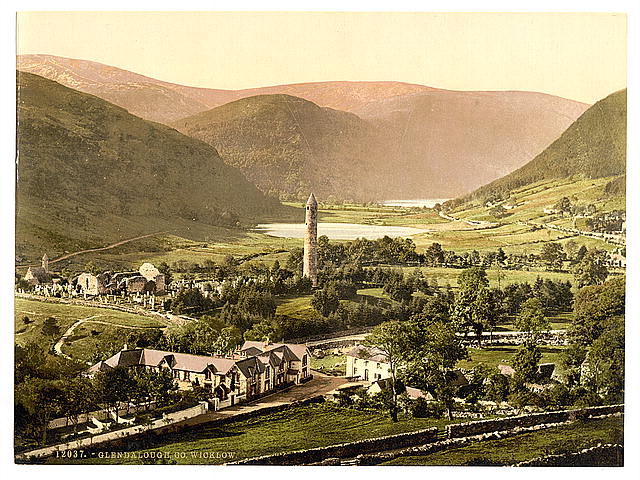

Moreover, he was renowned for his piety, charity and great leadership of two of the principle centres of Irish Christendom, Dublin –where he was Archbishop during the Norman Invasion – and Glendalough – that incredible medieval monastic city, founded by St. Kevin in the Sixth Century.

When my family and I lived in Co Wicklow, our home was between Dublin and Glendalough. And our parish church was dedicated to St. Laurence O’Toole. Often, I would pray, whilst walking through those holy sites of Glendalough – breathing the very air, walking the very steps that St. Laurence breathed and trod.

In the large chapel, the Cathedral of Ss. Peter and Paul, I would stand close to where the high altar once stood – the very place where St. Laurence celebrated Holy Mass – sensing a mystical holiness. Yet, I knew little about the saint. So who was St. Laurence and where did he come from?

Born in Leinster, in the area now known as Co. Kildare, it is said that St. Laurence came from an illustrious Irish family. His father was a clan chief, his mother a princess. Due to a family feud with the King of Leinster, at only ten years of age, young Laurence was taken by the king, as hostage. Badly treated, he suffered greatly.

But his father managed to bargain with the king, placing his son under the charge of the Bishop of Glendalough.

There, young Laurence resided for many years, studying and praying, with the religious community.

Providence had decided his fate, for at Glendalough, he was ordained a priest. It was, in fact, his heart‘s very own wish.

Then, on the death of the Abbot, he was requested by the community to preside in his place. He immediately began a vast programme of reform, bringing the Irish Church more in line with the Church of Rome. Respecting the sacred and traditional aspects of the Gaelic Church, he married them with the liturgical monastic movements in Europe, drawing particularly from the rule and reforms of the Augustinian Canons from the diocese of Arras, Northern France.

This in turn, brought about a spiritual renewal within the abbey, yet also in Dublin, Kilkenny, Carlow, Ferns and Baltinglass, where he founded Abbeys and convents.

In the first months of his administration, Glendalough was struck by famine. St. Laurence proved himself to be a most charitable father amongst his community, offering aid to all those in need. Both his spiritual direction and his charitable heart won him much affection and admiration.

His time in Glendalough, therefore, proved extremely fruitful, in terms of gathering disciples and gaining him a reputation as a great reformer, of saintly wisdom and powerful leadership.

When the Archbishop of Dublin passed away, in 1161, his reputation having spread far and wide, St. Laurence was unanimously elected to take his seat. He was inaugurated in 1162, by Gelaius, Archbishop of Armagh and Primate of all Ireland and took his place in Holy Trinity Cathedral (known also as Christ Church).

This appointment, of a native Irishman to the episcopal seat, marked an important transition in the history of Irish Catholicism. For much of Dublin was ruled at the time by the Viking settlers from Denmark and Norway. In fact the episcopal chair was also under Scandinavian influence, but the ascension of St Lawrence to Archbishop of Dublin can be seen as a turning point towards renewed Gaelic culture in that part of Ireland.

St. Laurence was seen by all, as a fair and charitable man – one who would be diplomatic and humble in his episcopal dealings. He indeed proved worthy of their trust.

In Dublin, St. Laurence continued his reforms of the Irish Church and became renowned for them. He made alterations to Holy Trinity Cathedral and erected many parish churches. He reformed the liturgy, laying greater emphasis on Gregorian Chant.

And he advanced his monastic renewal of Glendalough to the secular canons in Dublin, bringing them under the Augustinian rule, by which he lived himself. He founded a priory in conjunction with the Cathedral, whereby his canons would reside.

Yet much of his work, as Archbishop of Dublin, was taken up in political affairs. This involved dealing with the chaos and destitution resulting from the second siege of Dublin, in 1170, by the Norman invaders. This was in great part why he had been unanimously chosen for the post. For aside from his piety and strong leadership, he was a diplomatic soul.

Therefore, he was thought to possess those very qualities needed to form relations and to deal with the various differing factions and peoples who made up the city of Dublin at the time. This involved dialogue between the native Irish and the Norman and Viking settlers.

It also included relations with the English King, Henry II, who recognised himself to be Lord of the Norman settlements in Ireland.

King Henry visited Dublin in 1171, to further establish his Lordship, desiring not simply to be Lord of those areas of Norman settlement, but of all Ireland. Initially, the King’s motives went unrecognised, so he was cordially welcomed by the Archbishop.

But, once the King had departed, back to England, his motives were seen in their true light. Hurriedly, St. Laurence left as emissary, for England, to renegotiate with the King. He sped to Canterbury, where the King was staying. There, he reputedly spent a night’s vigil, in prayer beside the tomb of St. Thomas of Canterbury, only recently assassinated (in 1170) imploring the saint’s help.

Tradition has it that on making his way to the altar the following morning, to celebrate Mass, he was attacked. He suffered a terrible blow to the head with a staff. So violent was the blow that poor St. Laurence fell to the ground unconscious, believed to be mortally wounded. Yet, some moments later, he revived and ordered for some water to be brought to him.

He blessed the water and asked that his great head wound, from which blood poured, be bathed with this now holy water. Once administered, the bleeding immediately stopped. The saint celebrated Holy Mass and continued with his mission. (Apparently on his death, the crack in his skull was discovered.)

St. Laurence’s prayers were answered and his skills at diplomacy excelled. For the Archbishop negotiated an agreement between King Henry II and the High King of Ireland, Ua Conchobair (Rory O’Connor).

Known as the Treaty of Windsor, it stated the rights of Lordship for each king over parts of Ireland. It acknowledged that Henry II would only rule over those areas in which his Norman subjects resided.

St. Laurence sought further protection for the Irish Church from Rome, when, at the request of Pope Alexander III, he attend the Lateran Council of 1179.

Hearing his sincere and pious petitions for his country, the Pope appointed him legate of the Holy See for all of Ireland. This position gave the saint more power and impetus to reform the Irish Church.

Although St. Laurence had now secured political stability for both Irish nation and Church, problems still arose.

Rory O’Connor, High King of Ireland offended King Henry II of England and trouble broke out. St. Laurence journeyed again over the Irish sea to renegotiate with the King, but Henry would hear nothing of it. Instead, he took to Normandy. The saint followed him to France. Arriving there, he fell ill. So, burning with fever, he took refuge at St. Victor’s Abbey at Eu.

Tradition has it that St. Laurence knew his end was nigh. And, as Alban Butler wrote, he spoke these words of the psalmist:

This is my resting place for ever: in this place will I dwell, because I have chosen it.

There, on November the fourteenth, 1180, he gave up his spirit to God. His remains were buried in the Abbey cemetery, where they rested, until being brought to England in the mid fifteenth century.

But his heart travelled to its true resting place, in his beloved Dublin, where it resided in Holy Trinity Cathedral (Christ church), to which he personally gave it, on the day of his inauguration there.

Sadly, St. Laurence’s remains disappeared at the time of Henry VIII’s plundering of the monasteries. And perhaps just as tragic, in 2012, his heart was stolen from Holy Trinity (Christ Church) Dublin.

St. Laurence O’Toole, renowned for his leadership and charity, was also well known for his asceticism. Beneath his Bishop’s vestments, he wore a hair shirt. He refrained from eating meat, fasted each Friday and returned to Glendalough each year, where he made his annual retreat, in St. Kevin’s bed, or cave.

Many miracles are attributed to him. And they were so plentiful shortly after his death that he was canonised only forty-five years later, by Pope Honorius III.

Imploring the intercession of St. Laurence O’Toole, let us turn to the liturgy today:

O God, Who hast adorned blessed Laurence, Thy Bishop and Confessor, with countless miracles: grant unto us that by his merits and intercession we may be worthy to obtain health for our bodies and salvation for our souls. Through Our Lord Jesus Christ Thy Son, Who livest with Thee, in the unity of the Holy Ghost, One God forever and ever. Amen (Collect – from the Marian Missal, Dublin, 1959).

St. Laurence O’Toole, pray for Holy Church in Ireland.

St. Laurence O’Toole, pray for the faith in Ireland.

St. Laurence O’Toole, pray for us.

Foreword for Monarchy by Roger Buck

Buying Books at Amazon Through These Links Gives Us a Commission. This Supports Our Apostolate. Thank You if You Can Help Us Like This!

Comments

comments are currently closed

One response to “Feast of St. Laurence O’Toole”

Bishops are not “inaugurated” which is a poor choice of words. St. Lawrence O’Toole would have been consecrated a Bishop and then taken over the see. Bishops are not installed or inaugurated. They are always consecrated Bishops in the sacrament of holy orders.