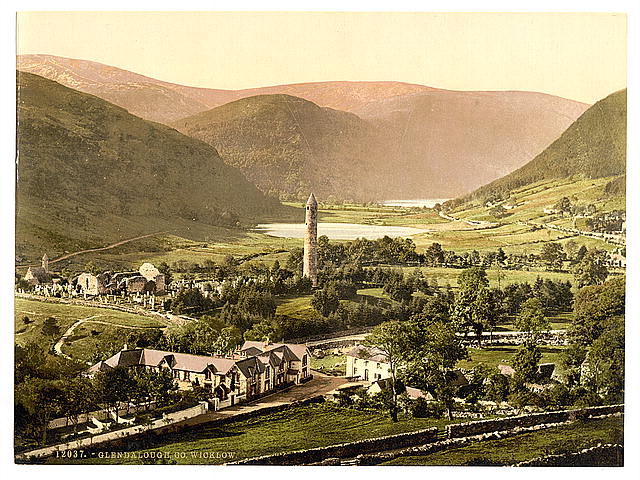

We turn, at last, to a project I have intended for long years now: reviewing Goodbye to Catholic Ireland by Mary Kenny.

Perhaps it would be better to say paying tribute rather than reviewing. Because for twelve years now, I have cherished this acute, haunting evocation of what Irish culture once was, before the rise of modern, globalised, secular Ireland.

Indeed, I needed this book, after first moving to Ireland in 2004. Living amidst the ruins of Catholic Ireland, I had to understand what destroyed her. And, personally, I did not buy the secular narrative foisted on us these days: Catholic Ireland collapsed under the weight of her archaic, overly-clericalised, ‘priest-ridden’ past, filled with scandal.

Whilst that narrative contains a small portion of alluring truth – similar to the way a heresy always contains alluring truth – it is not only simplistic, but pernicious and false. I needed better answers and Mary Kenny’s magnificent book provided a personal compass, whilst navigating my way through the destruction. That, and talking, talking, talking to countless Irish people who remember what the past was actually like and do not buy the secular narrative either.

I am speaking now more personally than is customary in a book review. I will continue in that vein. Because whilst this piece remains a review, it is more, as well. It is a tribute, like I say. But even more, I mean to sound a call: a summons to really think about Catholic Ireland and what it was and is.

Really think: Trying to do that about Catholic Ireland is difficult indeed in the climate of propaganda, lies, sometimes even near-hysteria, that now prevails in this country. Thus, what is desperately needed is balance and perspective. Goodbye to Catholic Ireland supplies that admirably. And for that reason, it is desperately needed.

For that reason, too, I will quote the book at greater length than is customary in a book review. I hope I may be forgiven here. The need to hear what Mary Kenny says is great.

Before we commence: a side note. We will also be repeating the name ‘Mary Kenny’ more than is customary. The reason is that, unusually, Mary Kenny requests this herself:

It would please me greatly if any review of this book did not refer to me as ‘Kenny’, as I have an abiding dislike of this vogue for describing women by their surnames only. In Ireland, a surname was a clan name, with no individual application, and certainly no Christian allusion: and Mary is an honourable baptismal praenomen to bear, which echoes so meaningfully the faith of our mothers.

The Heart of the Book

Moreover, the book is not simply about the Church. There is a great deal, too, concerning other aspects of Irish culture, including the Gaelic revival and the Easter Rising of 1916 which led to 1922. And much else besides.

Still, the focus, naturally, is on Catholicism and the approach is diverse: on the one hand, personal and subjective, one the other intensely analytical and immensely erudite on the subject at hand.

Perhaps the best single word for the book is: enquiry. There is an intensive search for truth here. The best way to illumine Mary Kenny’s quest is to listen to her:*

It is possible for a group of overseas visits say, to stay in Dublin for a week and to remain unaware of the Catholicity, as it was sometimes called, that once marked the capital and that was the most salient feature for visits and Dubliners alike in the past.

In the 1900’s, as C.S. Andrews remarked in his beguiling memoir Dublin Made Me, Catholicism gave Dublin its special flavour; as late as the 1960’s, Tony Farmar notes, young people at a university library could be seen getting to their feet and standing in prayer while the Angelus bell rang. No more. Holiness there will be, but it is, increasingly now, a private faith; the faith is not now an elemental manifestation of the culture, which it once was.

Indeed, one of the reasons why I wanted to explore this subject of the culture of Catholic Ireland was that it seemed to have been so overlooked in Irish studies. To be sure, there has always been serious scholarship about the early Irish Church, and about other sometimes ecclesiastical, sometimes political, aspects of the Catholic Church in Ireland; yet I was astonished, when I looked at the syllabus, at the end of the 1980s, of an ‘Irish studies’ course at a British university tha everything except Catholicism seemed to be included.

There was much material on colonialism and post-colonialism, on race, ethnicity and gender conflict and exploitation; class, pre-industrial and post-industrial social studies were attended to; but the overwhelming item, the irresistible magnet, the immovable force that had been as essential a part of the Irish mentalité as the very earth, the very skies, the very sea – tha faith – went unmentioned. It is assumed in many quarters that religion is simply ‘reactionary’: but it was, and for many, it still quietly remains, the faith of the people.

I suppose that when my mother died in 1991, I felt that, too there was an old hymn once called “Faith of our Fathers’, but truly, it was the faith of our mothers: and when an Irish mother died, the well-worn prayer-book with its holy pictures and sweet Novenas, the Rosary beads so often employed in love and protection for the whole family, were often the last witness to her enduring faith.

I wonder what bleak philosophy our generation will leave behind? Many of my own contemporaries in Ireland now declare themselves to be atheists or agnostics; this can be an honest admission of the way one sees life, but it certainly denies and invalidates all those prayers the grandmothers said, and sets at naught the sacrifices they made for the sake of all our immortal souls.

Riding the ‘Pill Train’: Mary Kenny’s Liberal Background

Is this, then, the work of a sentimental Catholic traditionalist, nostalgic for a rosy past, which never existed? All that talk about making sacrifices for ‘all our immortal souls‘ is bound to arouse suspicion! At least, if you belong to that coterie of doctrinaire secularists with knee-jerk reactions to any such language . . .

This is a pity – because such people are likely to be blinded to the sheer amount of erudition, nuance and shrewd analysis in this book.

Moreover, they may be blinded to just how liberal Mary Kenny’s credentials actually are, something which emerges when the author speaks of her youth:

I became involved in a campaign to launch a contemporary feminist movement in Ireland, calling itself the Irish Women’s Liberation Movement.

And she goes on to tell how Mary Robinson – future liberalising President of Ireland – was a fellow member of this feminist group. Robinson, however, appears to have been less radical – or at least sensationalist – in her youth than Mary Kenny. Thus, Robinson did not accompany the author on a crusade for contraceptives which took the form of what became known as the ‘Pill train’. As Mary Kenny describes the ‘Pill train’.

A group of Irish feminists – myself included – staged a defiant stunt in 1971 ostentatiously bringing contraceptives from Belfast [in the U.K. where they were legal] to Dublin [where they were not] by train and declaring them at Connolly Station.

‘Agitprop was not her style,’ Mary Kenny writes of the future president.

A Digression via G. K. Chesterton: ‘You Can’t be Moderate with a Battle-Axe’

At any rate, Goodbye to Catholic Ireland is neither traditionalist, nor simple-minded. Whilst simplistic secular agitators may not readily appreciate it, the author brings her own complex past to the book. And as a result, complex sensitivities inform everything she writes.

Another result is, in my view, remarkable balance. Everything here is treated with respect to liberal and conservative sympathies. For this very reason, the book can work as a healing agent for the malady that presently afflicts Ireland (the malady I described above in terms of near-hysteria).

Now, key to this malady is powerful propaganda, which works by focussing on the crimes of Catholic Ireland …

And crimes, there were, of course, aplenty. And hypocrisy. Just like there are plentiful crimes in modern secular Ireland. And plenty of hypocrisy.

And just like there was and is plenty of crime in every other time and culture too. And hypocrisy. And always will be.

For example, it is a sad fact that European children of the past – less so than American children I think – used to be beaten in school. In Ireland, unlike other countries, virtually all the schools were run by Catholics. And so one hears awful stories – sadly true – about severe Catholic nuns, brothers etc. And in the near-hysteria prevailing today, one blames the Church.

It is not that the Church should be exonerated from her manifold failures in the past. It is that one-sidedness is used to fuel hysteria.

My family is basically British and I have spent most of my adult life in Britain. In the course of time, I have heard hair-raising stories of corporal punishment in British schools. But people never use this as a propaganda tool to lambaste the secular British establishment of bygone years!

Not so in contemporary Ireland. These terrible stories of Catholic teachers are used to beat the Church.

Why do we not beat secularism, I wonder, for all its failures in the past and present?

For example, in Ireland today we have levels of crime, murder, suicide, mental illness and social breakdown that would have made Catholic Ireland’s blood run cold. We are also on the way to massacring the unborn.

Is it not possible that, in future days, the Irish will berate today’s prevailing secularism, the way they now berate Catholicism? Personally, I hope not: hysteria helps no-one.

However, a time will come, when Ireland, along with the rest of the West, will do massive penance, not only for the massacre of the unborn, but for unleashing the forces that have led to the dreadful anguish of our age.

What I am writing now is hardly subtle. You will readily realise I want to make a point, good reader! In doing so, people may regard me as a Catholic zealot anxious to defend the faith.

I declare my intentions openly: I see an agenda of hate and hysteria in Ireland 2015 that has advanced significantly since Mary Kenny first wrote her book in 1997. And I see Mary Kenny’s book as a means to address the destruction wreaked by that agenda.

G.K. Chesterton once joked: ‘You can’t be moderate with a battle-ax’. I am not a moderate. Make no mistake, reader. In what follows you may feel someone wielding a battle-axe. However, it is I – not Mary. Compared to mine, Mary Kenny’s style is subtle, moderate and liberal.

Contextualisation, Censorship and Catholic Ireland

Writing in 1997, I do not imagine Mary Kenny felt the same horror I do today. Still, I find her more moderate approach invaluable. Besides seeking balance, another beautiful feature of Mary Kenny’s book is contextualisation.

Here I mean the author constantly aims to provide context, accounting for the fact that people in the past thought and acted differently – and not just Catholics.

For example, let us take the issue of censorship. Today, Catholic Ireland is widely portrayed as prudish, repressed – an authoritarian kill-joy which did not cater sufficiently to our basic human needs for sex, drugs and rock and roll.

All this is commonly ascribed to Ireland being ‘priest-ridden’. This, of course, is exactly how Britain always described Ireland. Mary Kenny quotes Britain’s Observer in 1995:

Political vision and world-class talent have transformed Ireland from a priest-ridden backwater to a confident nation.

And the fact that many Irish now accept the ‘priest-ridden’ propaganda as fact shows how Ireland trusts British secular attitudes more than her own past. ‘Britain was right; we were wrong: unconfident, backwards and “priest-ridden”.’

Yes, something simplistic like this transpires in many Irish minds today. But truth, as Mary Kenny demonstrates, is something is infinitely more complex than soundbites.

Thus, she discusses how Irish censorship was hardly limited to Catholicism, but, in many ways, was initiated by the Gaelic League (itself originally a Protestant phenomenon, associated with Irish Protestants such as the poet W.B. Yeats):

The Gaelic league began to crusade against the ‘vulgarity’ of ‘English commercial culture’ in the early 1900s . . .

It may seem ironic that the censoring spirit was in part activated by the … agenda spelled out in 1900 by [Protestant Gaelic Leaguers] Douglas Hyde, AE, Lady Gregory and Yeats, but it is also quite logical. As soon as you begin to arouse aspirations about constructing a pure and unsullied culture, you are effectively on the road to censorship.

Mary Kenny further contextualises Irish censorship by indicating how much the Protestant community supported it after independence in 1922:

The Church of Ireland Gazette … the official voice of Protestant Ireland … wholeheartedly supported censorship of the cinema which had been introduced in 1923. ‘We are in complete agreement with [the film censor],’ it wrote in 1925. ‘There is no more insidious danger to public and private morals than the cinematograph …

Cinema shows are visited by people of every class and every walk of life … For that reason it is highly important that films should be subjected to a strict censorship.’ Even so their readers wrote to complain about the ‘savagery’ permitted on the screen at the picture house – and on Sundays too!

Taking all things into account, then, it is not surprising that:

From the end of the 1920s until the middle of the 1960s, Catholic Ireland was to develop an increasingly fierce reputation for censorship.

The censorship in question, though it enraged writers, seems to have been broadly supported by the majority of the people who, whenever the subject came up, called only for more of it, or deplored the laxity of its practice.

The most zealous agents of censorship were the library committees whose fervour in suppressing literature ‘likely to subvert public morality’ is ascribed to the fact that they were responding to complaints from the public. The censorship, often described as an authoritarian, even a ‘fascist’ control of Ireland was, or became, largely market-driven [Italics mine].

And the author continues to contextualise:

At the time that the Censorship Act was passed in 1929, it was not out of tune with the spirit of the age elsewhere. At this period many books were still banned in Britain (including Joyce’s Ulysses, quixotically never banned in Ireland, and much of D.H. Lawrence), and the works of Zola and Thomas Hardy were regarded by the National Purity League in England as ‘pornographic’ and were liable to be confiscated at Dover if found in an Englishmen’s suitcase.

All this reveals how very, very different Western attitudes were until, very, very recently. Alas, our sound-bite ridden world fosters cultural amnesia, which only fuels simple-minded judgments about ‘priest-ridden’ Ireland.

Birth Control and Catholic Ireland

Here is why balance and contextualisation is so urgently needed. To her great credit, Mary Kenny continues in this same vein, concerning the ban on contraceptives that once existed in Ireland.

Thus, many years later, the angry young woman who once boarded the ‘Pill Train’, now writes with mature equilibrium:

Everywhere, birth control had to fight for respectability over decades. The French only legalised contraception in 1967.

Perhaps some might object that even hyper-secular France was still a Catholic country, unduly influenced by priests. What is telling, then, is where Mary Kenny turns her attention to Protestant Britain:

Birth control did not begin to be respectable in Britain until 1958, when a government Minister, Iain McLeod, daringly agreed to pay an official visit to a family planning centre, and even then it was still a matter of spacing children rather than avoiding them; certainly birth control was not available so that sex could be indulged in for mere pleasure, then democratic called ‘the avoidance of responsibility’ [Italics mine].

The author also considers Humanae Vitae – Bl. Pope Paul VI’s 1968 encyclical affirming the Church’s ban on artificial birth control:

The Catholic Church itself travelled quite far in Humanae Vitae – a sensitive and even poetic document, actually, and still a good read – in acknowledging the case for family limitation, for respecting women’s changing role, and for population concerns.

And she treats with respect, conservative concerns that:

The pill did deal a serious blow to marriage – certainly divorce increased, as did cohabitation, after its introduction, as though once children became an optional extra to the relationship, marriage itself became less meaningful.

Was Catholic Ireland Insular?

Let us turn from the familiar issues of birth control and censorship to another common trope in modern secular culture: the claim that Catholic Ireland was closed-off from the world. As Mary Kenny writes:

I have frequently … heard it alleged by well-informed people, that the culture of Catholic Ireland was essentially ‘insular’ and ‘anti-intellectual’. Yet the evidence is quite to the contrary. Catholic Ireland was anything but ‘insular’.

It was, indeed, persistently outward-looking, partly in consequence of its great involvement with and concern for the universal Church.

To substantiate her claim, the author intensively studied Irish journalism from the past, pouring over archived periodicals from the 1890s onwards. What she found reveals an Ireland in no way as closed as people imagine:

An extraordinary debate in 1897 [in the parliament in France was] reported in close detail, when the anti-clerical deputies proposed the demolition of the Sacré Coeur basilica in Montmartre … The Irish Catholic’s parliamentary report must be one of the best archives in the English- speaking world for reporting such debates. It also had detailed and knowledgeable front-page reports from London, Rome and Madrid. …

Yet the Irish Catholic was not a specialist, foreign-affairs publication, but a middle-market Catholic paper aimed at ordinary Catholics who liked a weekly newspaper with a variety of items. Neither was the more populist – some would even say ‘simple’ – devotional monthly, the Irish Messenger of the Sacred Heart in the least degree insular. It, too, was concerned to defend the universal Church and to look outward towards missionary endeavours …

It really is a little naïve to claim … that the Irish are, for the first time, becoming truly international through the benefices of the European Community. There is much ground for claiming that Irish Catholics were in some respects more international in the 1890s, through the benefices of the Latin Church.

The charge that Catholic Ireland was ‘anti-intellectual’ also seems to me to be at least in some senses mistaken. It is true that Irish Catholicism did not encourage too much independent thought – there was a certain horror of ‘private judgements’ – and it is true that Catholic Ireland was zealously keen on censorship, a policy wholly supported by the democratic will, and overwhelmingly market-led.

Yet it was not anti-intellectual in the sense of being philistine. …

There was a genuine, deep-seated love for learning and scholarship …

A sermon published in the Irish Catholic in 1940 mentions Marx, Rousseau, Croce, Gentile, Voltaire, Darwin, Huxley and Haekel and uses the word ‘Weltanschauung” (‘world-view)’ quite casually. It also refers to Oscar Wilde as a beautiful example of redemption through suffering …

The Catholic Church in Ireland was traditionally prudish, repressive and authoritarian, to be sure. It could also be very fierce. But it was not, in my judgement, anti-intellectual, and it was certainly not insular.

A Rich, Haunting Evocation of Catholic Ireland

Thus far, we have focussed on Mary Kenny’s ability to bring balance to contentious issues. Really, I should say: restoring sanity.

That, however, could give the impression the book is mainly concerned with these things. It is not! (Once again: I am the battle-axe here. Not the author.)

No, there is so much more to the book. Through an eclectic mix of consulting academic studies, old archives and her own personal memories, Mary Kenny evokes how very different Catholic Ireland once was, not only from herself today, but, indeed, the rest of the English-speaking world.

For example, it is striking how much Irish Catholic culture still permeated even urban and middle-class Dublin well into the 1960s:

In the libraries at University College Dublin, in 1963, the majority of students still stood up for the Angelus to pray, at midday and at six o’clock in the evening.

V. S. Pritchett observed, in 1963, that nearly everyone still crossed themselves when passing a church in Dublin. On the Feast of St. Blaise in February 1963, it took twenty-two priests to bless the throats of the thousands attending a blessing service Mass at Merchants Quay, Dublin …

The main complaint, in one study, was that the priests were in such demand that they were ‘run off their feet’ performing pastoral duties; far from being ‘priest-ridden’, people said there weren’t enough priests to perform the full range of parish duties.

Staying with the 1960s, Mary Kenny also notes:

The American Jesuit, B. F. Biever, in a study carried out in 1963-4, found that nearly ninety per cent of his sample agreed with the proposition that ‘The Church is the greatest force for good in Ireland today.’

Eighty-eight per cent of the sample refused to declare the Church ‘out of date’. Respondents said things like, ‘When you’ve got the truth, lad, you don’t worry about keeping up with the times,’ and ‘I wouldn’t change a thing the Church is doing.’ … ‘The church may not be getting us jobs, but it is keeping our people happy and with their feet on the ground.’

How all this flies against ‘received wisdom’ today! But reading Mary Kenny’s book and living in Ireland, I cannot shake the conclusion: Ireland was a far happier place then, than it is today.

It was also more honest, in many ways at least. Mary Kenny herself seems quite affected by the recurrent emphasis on honesty, she finds in old Catholic journals:

The Irish ecclesiastical authorities were sticklers for honesty … and extremely keen to underline the point that you could not be absolved at Confession for dishonest acts unless you made restitution to the person you had cheated or defrauded, at least to the best of your ability …

Exhortations to honesty must have had their effect (they certainly had an effect on me when reading them): the Irish newspapers in the 1950s had long ‘lost and found’ columns, in which people advertised the objects that they found on buses, trains, in cafeterias, and so on …

[All this seemed] to give people a sense of conscience about honesty and there were beneficial effects in the extraordinarily low rate of crime. Outside of Dublin the crime rate was about ten offences per thousand of the population [including things like] riding a bicycle without a light; in 1950 there were four hundred and sixty-nine men in prison in the Republic, and sixty-eight women. (By 1990 this had more than quadrupled.)

What can I say? I have no figures handy, but one knows, today, twenty five years later, it is likely much worse.

More recently, however, I have seen a reliable report indicating a sixfold increase in suicide and fourfold increase in murder since 1970 (rather than 1950) and if present trends continue, there is still worse to come …

An atrocious irony exists here – indeed scandal. In Ireland’s recent gay ‘marriage’ referendum it was frequently argued that voting no might lead to gay people committing suicide! And yet secular Ireland is far more suicidal than Catholic Ireland ever dreamt in its worst nightmares …

Vatican II and the Rise of Modern Secular Ireland

Moving on, the book’s final chapters contain a nuanced, probing account of how and why Catholic Ireland changed from the 1960s onward.

This is needed immensely. For these days, many blame the collapse of the Irish Church on the appalling abuse that emerged in the 90s – something we consider shortly. Decidedly, this is a factor – amongst others, I would say, including globalisation, secularisation and increasing capitalism everywhere.

However, on re-reading Mary Kenny’s book recently, I was struck by how much she ascribes the fall of Catholic Ireland to the 1960s changes in the Church.

Again, the author has studied the archived Catholic journals of the day. What she finds is a testimony to destabilisation and disorientation. All of which is not surprising, when, seemingly out of nowhere, strange novel concepts began popping up, including a startling new left wing emphasis:

Having been ferociously anti-communist when communism posed the international threat to Christianity, now the Irish Church seemed to have a softer view of Marxism, as indeed it had softer views on everything. The Irish Messenger of the Sacred Heart made several indulgent references to Karl Marx and his ideals, and at one point bracketed [Marx] with John F. Kennedy and Patrick Pearse as ‘men who live on in the memories of people, inspiring them to continue work which they themselves started.

This sort of volte-face was, of course, only one amongst many shifts, most notably in terms of liturgy and ecumenism. It is not surprising how much sheer confusion was generated – something Mary Kenny discovered in old letters that Catholics wrote to these periodicals. Some examples:

‘I have heard it said that we Catholics should not talk too much about Our Lady as it embarrasses Protestants and could be an obstacle to unity.’

‘Why do they keep on changing the Mass? I wish they would stop and leave it alone.’

‘I get very upset by the strange ideas I sometimes hear nowadays even from some priests.’

‘I’m still terribly muddled about this “follow your own conscience” business.’

‘I am worried about priests’ casual attitude to the Sacred Heart.”

‘My niece who is a nun told me I should not be fussing around with devotions – not indeed that I have many. I … always try to get to Mass and Holy Communion on the First Friday. Are these things no longer approved of by the Church?’

‘My parish has a new altar which is very plain, with no decorations or carvings. Why does it have to be so plain?’

Another issue that comes up is a new spirit of laxity:

‘A young priest said to me the other day that the Church should never have made things tough for its people,’ wrote a trade unionist in 1969. ‘He said evening Mass was better than getting up early on Sunday morning and that the old parish sodalities were well gone and that religion should be made handy for everyone.’ What was comfortable and accessible was now replacing what was vigorous and demanding.

The new laxity, of course, was tied to a decided shift from old notions of sin to new notions of tolerance and acceptance, particularly where sexuality is concerned. As the author writes:

Out go Thomas Aquinas and … the distinction between the higher nature of man’s soul and the lower nature of man’s flesh – and in come Freud, Erikson, Adorno, D. H. Lawrence and Carl Rogers, some of the writers now admired by Catholic theologians. ‘Repression’ was the new evil: sexuality was a part of our ‘personhood’ to be accepted, not repressed and kept forever under control.

Along with this, homosexual acts began to be defended:

There was, also, a noticeable new questioning of traditional attitudes to homosexuality, which had previously been pronounced ‘against nature’ – Christianity, Judaism and Islam having historically held this view in common. A characteristic example of the new liberal tone among the clergy was a strong article in the Furrow in 1979 about the pastoral care of homosexuals, written by Father Gallagher.

Gallagher warns his fellow clergy; we must challenge the notion that homosexual acts are intrinsically evil or ‘imperfect’. Homosexuality must be seen as part of a proper understanding of sexuality ‘in its wider sense’.

And this wider sense was arising because sex was no longer simply about procreation: birth control had altered perspectives. ‘We must take cognisance of the change emphasis on procreation in a theological understanding of sex. It can no longer be regarded as the single dominant norm by which all sexual behaviour is judged. The reality of personal sexual encounters is too wide to be compressed into the univocal notion of procreation.’

Hugh Hefner had said that after the pill, sex was about recreation, not procreation and this change the whole approach to sexuality. Here was a Redemptorist using (perhaps unconsciously) the ideas of the founder of Playboy magazine as source text.

To my mind, the former 1960s militant feminist gets to the crux of the matter, when she writes:

As the 1960s slogan had it – if it feels good, do it! What feels natural, is natural. The crucial change that the 1960s had brought about was this shift from reasoning to feeling.

To this, there is little else to say, except, perhaps: amen.

However, the author raises a telling issue, one that seems to me particularly relevant to the largely homosexual abuse scandals that would rock the Church thirty years after Vatican II:

What is interesting is why, at this point, from about 1979 onwards, homosexuality moved centre-stage in the texts of Irish Catholicism. It may be – is likely, indeed – that a higher percentage of priests were now homosexual, since so many of the heterosexual men were quitting the priesthood to marry, or that more heterosexual man were deciding against the priesthood as a vocation because they wished to marry. It is thus probable that the percentage of homosexual clergy became more dominant.

Abuse in the Irish Church

Thus we arrive at the appalling sex scandals that erupted in the Irish Church as the 1990s began. Here is a terrible, all-too-familiar story and we will not enter into it extensively here. You can find copious amounts of it in the mainstream media. In this review, my purpose has been to air the issues that are not familiar.

Again: I mean to bring balance—as Mary Kenny does—by pointing out the factors the mainstream media ignores (often deliberately).

Here I may sound heartless to the immense suffering of a small section of Irish children who suffered terrible sexual abuse. For the popular idea in the Irish mind – at present – is certainly not that Irish Catholicism has been ruined by post-Vatican II de-sacralisation! Nor is globalisation or capitalism talked of much.

Rather, it is widely supposed Irish Catholicism destroyed itself by its own criminal activity. What many Irish will tell you, today, is that revolting sexual abuse by priests, followed by appalling attempts by Bishops to conceal it – here is what shattered the Church in Ireland.

Undoubtedly, a pathological evil has afflicted a small percentage of Irish priests in recent decades. And it seems to me that it was exacerbated by the liberalisation of the Church after Vatican II.

But no-one can or should deny that innocent young people have been violated – often scarring them for life. Nor can anyone ignore the sick clericalism, which cared more about protecting the Church’s reputation than safeguarding the lives of the innocent. No-one can doubt how many Irish felt betrayed. As Mary Kenny writes:

People were flabbergasted … And bitter. ‘These are the men who were telling us how to behave,’ a woman in Kinsale … said to me resentfully.

Yet, as ever, the author contextualises by remembering the vast number of Irish priests (around ninety-six percent) who were innocent. She also invokes situations in other non-Catholic countries, such as Wales (which is almost as Protestant as Scandinavia):

Paedophile scandals begin to change perspective as time passes and data grows: Ghastly child abuse crimes [occurred] in British care homes … The Waterhouse report in Britain uncovered an extensive system of child abuse in Welsh children’s homes during the 1980s: hundreds, perhaps thousands, of children were subjected to paedophile cruelty and abuse.

Expert opinion is now tending to the view that anywhere there are children, paedophiles are drawn. This excuses nothing, but it explains something.

One should never seek to excuse the inexcusable. Yet, one should always seek to create understanding … I salute Mary Kenny for this. For now, we move on, but I write more about this subject elsewhere at this site (for example here) and I have also addressed it at length in The Gentle Traditionalist, my upcoming book about Catholic Ireland.

In Conclusion: An Ark to Save the Soul of Ireland

How much there is in this book. Far, far more than we can cover here! Other topics include Irish missionary activity abroad, the Troubles in the north of Ireland, and the immense role women played in Irish Catholicism. As the author writes:

Despite accusations of ‘patriarchy’, no one has forged, sustained, or upheld the faith of Catholic Ireland more purposefully than the women of Ireland: that also is a historical fact. There is a famous Irish hymn of old called Faith of Our Fathers, but it is even more the faith of our mothers, and our grandmothers, and that emerges whenever people in Ireland tell the story of their childhood, even to this day.

It was the mothers and the grandmothers who transmitted the faith. In remembering and recalling the essence of Catholic Ireland, perhaps I, in my turn, feel that it is part of my historical duty as an Irish mother to transmit and recall what we inherited from this faith of our mothers and grandmothers, which they regarded as our Irish soul and a pearl beyond price.

To transmit and recall: here is the great merit of this book. Mary Kenny opens out a rich, fascinating account of forgotten beauty in Irish Catholic culture and she analyses meticulously what destroyed that beauty. I cannot resist quoting her one last time:

At all times in history, the Catholic church in Ireland came from the heart, soul and will of the Irish people. It was not an invading or occupying force: it grew organically out of the soil, the land, the sea, the climate, the sky. At all times it reflected the values of Irish society, as well as reacting to values and trends in universal culture. …

Mrs Catherine Broadberry, who was born in Co Meath in 1930, wrote to me in the middle 1990s and described the Catholic values of her childhood. The faith, she say, was ‘very precious really, something very wonderful, still ongoing and deeply imbedded with us: part of us. We learned so much from our parents, within our own homes, and saw also the results of our labours, which to me were “labours of love”.’

I have with me still my mother’s well-thumbed prayer book, with its devotions ad prayers so ardently offered up: thus the faith was transmitted, as a pearl beyond price, which should raise our hearts and fill our souls with rapture.

What else to say? Mary Kenny ‘s writing is warm, lively and accessible – often humorous. This is not an academic book, yet it is far more acute, probing and original than the vast majority of academic books I have read!

I should also note the book exists in different editions. I mainly used the original 1997 version for this review. But I recently bought an updated 2000 American edition. The latter has a new foreword by the author and an appendix by noted Irish figures – such as Pierce Brosnan and Andrea Corr – who recall growing up in Catholic Ireland.

Also, the author appears to have rewritten it somewhat, inserting new passages. I sense the later edition has been adapted to render it more accessible to an international audience. Beware, however! The updated American edition is missing copious notes from the earlier 1997 edition, which, perhaps, the Americans thought would only interest Irish specialists. (There is also a British edition published in 2000. I imagine it is the same as the American one, but have not been able to check.)

Whichever version you read, this book is quite simply indispensable to anyone who cares about Irish Catholic culture. Yet Goodbye to Catholic Ireland is likewise invaluable for understanding Catholicism’s fate anywhere in the modern West. The book also bears repeated readings. I have read it something like four times myself now – and I still profit with every re-reading.

Thus, I have meant to review this book for years now. I am so glad to have finally achieved that task. With The Gentle Traditionalist – my own book about Catholic Ireland – about to be published, I am launching into more public activity to guard the Soul of Ireland.

For, as I recently wrote here, it seems to me an Ark must be constructed to carry Catholic Irish culture amidst the deluge of secularisation and indeed, the modernist tendencies within the Church herself.

Mary Kenny’s book is critical reading for the construction of that Ark.

Truly, I cannot recommend it highly enough.

*Note: Here in this passage and throughout this review I have taken the liberty of breaking down longer passages in the book into shorter ones on-screen. (I often do this at this site: books and screens are two different media and comprehension benefits from much more ‘white space’ on a screen than the printed page. I heartily wish other websites would adopt this practice. My own tired eyes would certainly appreciate it!)

Foreword for Monarchy by Roger Buck

Buying Books at Amazon Through These Links Gives Us a Commission. This Supports Our Apostolate. Thank You if You Can Help Us Like This!

Comments

comments are currently closed

6 responses to “Goodbye to Catholic Ireland by Mary Kenny: Review and Commentary”

[…] « Catholic Traditionalists and Liberals: The Tragic War Goodbye to Catholic Ireland by Mary Kenny: Review and Commentary » […]

“Undoubtedly, a pathological evil has afflicted a small percentage of Irish priests in recent decades.”

Who says it is pathological?

Criminal – certainly.

“The old morality accused a man of stealing and shut him up for a year. The new morality accuses him of kleptomania and shuts him up for life.”

Manalive, G. K. Chesterton

+JMJ+

Thanks for this review. I will be ordering this book soon.

Another great read about Ireland prior to it’s secular collapse is The Soul of Ireland by W J.D. Lockington, a priest. It is bittersweet. In it are the roots, the foundations of the restoration of Catholic culture, once so rooted in the family, now being blown to bits by pagan/Marxist/Masonic infiltration of the Church, and Western Culture as a whole.

Our Lady of Fatima, Pray for Us.

AMDG

James

[…] « Goodbye to Catholic Ireland by Mary Kenny: Review and Commentary […]

[…] of sexual abuse and the Catholic Church in Ireland, I also want to point the interested reader to one of the personally most important pieces I’ve yet published on Catholic Ireland (here). I pray that it might help, in its own very small way, to bring clarity and balance regarding […]

[…] nation. And thus I was extraordinarily gratified that Irish journalist Mary Kenny (and author of Goodbye to Catholic Ireland – reviewed here) clearly recognised this in her review for my […]