Apparently, the English singer Morrisey has Irish roots. Morrisey, however, seems passionately devoted to English culture. Thus, he once wrote a song called Irish Blood, English Heart.

With myself, it is something of the reverse. Although I was born in America, my blood appears to be mainly British (English and Scots) with a little Irish thrown in. (My late mother’s name was Conneeley and her grandfather came from Galway. There is also possibly more Irish mixed with the Scots – though I have not yet established that.)

But since first coming to live here in 2004, I have felt haunted by Ireland. Simply put, Irish culture is far more fascinating and compelling to me than either American or British civilisation.

This Hibernophilia remains deeply mysterious to me. I feel a passion for this land, that neither can I explain, nor can I feel for either my native America or Britain (where my parents were born).

All this finds expression in my new book The Gentle Traditionalist.

Indeed, this is so much so that, in the book’s introduction, I describe it as ‘a Valentine for Catholic Ireland’.

I am grateful if the Irish feel I have succeeded to express my love for their nation. And thus I was extraordinarily gratified that Irish journalist Mary Kenny (and author of Goodbye to Catholic Ireland – reviewed here) clearly recognised this in her review for my book:

This is one of the most unusual books I’ve ever read. It’s a spiritual journey, a romance and a quest; a reflection on history and a discourse on faith and tradition; a fable and a meditation about place and location. It’s sometimes surreal, sometimes eccentric, sometimes didactic, but written throughout with passion and engagement, with a touching and deep-seated love for Ireland and for the sweetness and humanity that have been embedded in Irish country values.

Some readers will want to argue with the text. Others will be stimulated to ponder the question whether in the course of modernisation globalised Ireland has lost the essence that was its soul.

Still, lest we give the wrong impression, let me hasten to add my book is not only about Catholic Ireland!

No, there are many other themes to the book – global themes – which, not surprisingly include the major themes of this website.

These include, for example, the crisis in the Church today and why secularism gets away with murder …

Nonetheless, despite the global themes, Ireland obviously plays a major part in the book.

Thus, writing it was a tricky balancing act: trying to pen both my valentine for Ireland AND a book that might appeal to Catholics across the planet.

Still, I think I pulled it off.

Because the book is very much about the global situation of the Church and whilst Irish elements are prominent, I think these are sufficiently explained so that non-Irish readers can easily understand them. (Indeed, the Irish may think I have overly simplified complex Irish issues in presenting them to a global audience!)

At any rate, although my book is mainly a fictional dialogue, I also included a non-fiction introduction where I talk about Ireland, trying to explain her situation for a non-Irish audience.

Now, we recently we have presented numerous fictional extracts from The Gentle Traditionalist– including the first chapter here.

Today, we have something different: two non-fiction extracts from that introduction, which have to do with explaining my Irish Valentine.

It’s tricky ripping extracts like this from a greater context. But hopefully they will make some sense. Here they are . . .

First Non-Fiction Extract: Ireland and My Native America

In the first shorter extract, I venture a somewhat controversial notion which I expand on in the book. It concerns what I consider a sometimes overlooked factor in explaining Ireland’s extraordinarily rapid liberalisation in recent decades.

That factor is the influence of my own native culture. As I write:

We now face a grave situation whereby Anglo-American culture dominates the planet.

All this has been poignant and painful for me since coming back to live in the northwest of Ireland, just over two years ago.

I am gravely concerned for the fate of Catholic Ireland, overwhelmed as it is by the two cultures, from which I stem.

Daily, I ask how the Irish spiritual genius can be preserved, so that Ireland does not simply become a second-rate clone of the liberal Anglo-American world.

Some may wonder if I excessively blame my own countries of origin. What of homegrown Irish cultural and political leaders who have steered Ireland on her present course? What, for example, of current Prime Minister Enda Kenny, who (against electoral promises and without a referendum!) recently legalised abortion in Ireland?

Of course, Kenny and Irish folk of his ilk must be held accountable! And, admittedly, there is a native Irish liberal tradition (even if much of that owes to the small Anglo-Irish Protestant population that remained after Ireland achieved independence from Britain in 1922).

Obviously, there are also other factors destroying Irish Catholic culture. Most notably, the appalling sexual abuse that occurred in Ireland—which we consider in these pages [see my extract regarding this here]—has taken its toll. Clearly, an entire complex of issues is at work, rather than simply “Anglo-Americanisation.”

Nonetheless, it is often remarked how much the young have transformed Irish culture, abandoning the “faith of their fathers.” And the young—along with by now middle-aged Irish elites—have grown up in an age wherein Ireland became awash in British and American media like never before.

Thus, for example, the rock stars who pervaded these generations’ formative years were, above all, British, but also American. They were not, however, Italian, French or Spanish!

Being British and American myself, I cannot help but feel acutely conscious of how much my own culture has thoroughly pervaded this country.

Thus, I also sadly note that the majority of newspapers the Irish read are of British origin. And, on the rare occasions I watch Irish television, something hits me in the guts: just how many English or American productions I see. It runs the gamut from talk shows and Hollywood blockbusters to soap operas and cartoons: everything from Oprah to The Simpsons.

I am hardly alone in these concerns. Rachel Shearer at the internet site IrishCentral writes:

There are many American traditions that we slowly adopt over the years. Nickelodeon had a lot to answer for in the late 1990s as Irish children began to develop inexplicably strong U.S. accents and the country was met with an epidemic of juvenile eye-rolling and answering “whatever” to almost everything. I have strong memories of saying “duh!” about 400 times a day thanks to Sabrina the Teenage Witch and thinking I was the coolest kid on the block for having learned this spicy, exotic lingo.

“Duh” and “whatever” are obvious manifestations. More subtly, I maintain, contemporary Irish cultural attitudes owe far more to the liberalism stemming from London and Hollywood than is often acknowledged. Very recently, Ireland voted for same-sex “marriage” and the yes vote was carried by the young. In France and Spain, I noticed a marked difference. There the Anglo-American influence is comparatively much reduced and even with the young, there are mighty movements against same-sex “marriage” that would confound the liberalized youth of Ireland today.

Second Non-Fiction Extract: Pearse, Dev, 1916 and more

Later in my introduction, I speak of the 1916 Easter Rising in Dublin, whereby mainly Catholic rebels commandeered key buildings in the city. There, Patrick Pearse proclaimed the Irish Republic, free from Britain.

The rebellion, of course, was immediately suppressed by the British and the rebel leaders immediately executed by the British—except for Éamon de Valera who, mysteriously, was spared.

And having recounted that briefly for the non-Irish reader, I then I go further into the crisis Ireland faces today and what can be done . . .

Before closing, I should like to venture a few last things about Ireland. My debt to this ancient Christian land is enormous. How much unfathomable treasure I have drawn from her profound wells of Christianity! And how my heart has been warmed by the uncommon kindness of her people! I have lived in seven countries in all and Irish society, still strikes me, even today, as the most human.

All this is beyond anything I can possibly express here […]

Suffice it to say, I have a love affair with Ireland and I consider this little book a love letter: a valentine for Catholic Ireland.

However, it is not enough to wax maudlin. True love entails more than sentimentality. It demands care, compassion and effort for the beloved who suffers. Today, the Ireland that I love suffers greatly.

I write these words in the latter half of 2015, as this country anticipates a milestone in her history: the one-hundredth anniversary of the 1916 Easter Rising, which led to the modern Irish Republic.

Today, secular Ireland appears distinctly uncomfortable with this centenary. There are different factors for this. Some strike me as noble in essence, others less so.

On the noble side, some feel the Rising was not a Just War. They also rightly recoil at the terrible violence committed by the IRA in recent decades and start to wonder whether the 1916 revolutionaries—including the aforementioned Patrick Pearse and Éamon de Valera—might be little more than terrorists. (Truly, their attitudes would shock many of my fellow Americans who never entertain such thoughts about their own founding revolutionaries – even though the Irish revolution was far less bloody than the American one.)

Less nobly, modern Ireland uses different routes to circumvent the “problem of 1916.” One route is to dismiss the rebels as Catholic fanatics, whilst another is precisely the opposite: to claim the revolutionaries were, in reality, more groovy, “Progressive” and multicultural than the facts attest.

Admittedly, Pearse’s words in 1916 occasionally lend themselves to this sort of interpretation. However, the more I study the Rising, the more clearly I see, what R.F. Forster writes in his historical masterpiece, Modern Ireland:

An intrinsic component of the insurrection (for all the pluralist window-dressing of the Proclamation issued by Pearse) was the strain of mystic Catholicism identifying the Irish soul as Catholic and Gaelic.1

This notion is only strengthened by what transpired after the Rising. Upon achieving independence, Ireland opted—with vast popular support—for a far less secular system than Britain, one in which Church and State were interwoven in ways unthinkable in other English-speaking countries. Thus, for example, new laws were passed—again with democratic support—promoting tighter censorship and restricting divorce and sale of contraceptives, amidst other measures favoured by the Catholic morality of the vast majority of its citizens.

As noted above, a new constitution was voted in, which rooted ultimate authority not in simply the “consent of the governed,” but rather the Triune Christian God:

In the Name of the Most Holy Trinity, from Whom is all authority and to Whom, as our final end, all actions both of men and States must be referred,

We, the people of Éire,

Humbly acknowledging all our obligations to our Divine Lord, Jesus Christ, Who sustained our fathers through centuries of trial,

Gratefully remembering their heroic and unremitting struggle to regain the rightful independence of our Nation,

And seeking to promote the common good, with due observance of Prudence, Justice and Charity, so that the dignity and freedom of the individual may be assured, true social order attained, the unity of our country restored, and concord established with other nations,

Do hereby adopt, enact, and give to ourselves this Constitution.

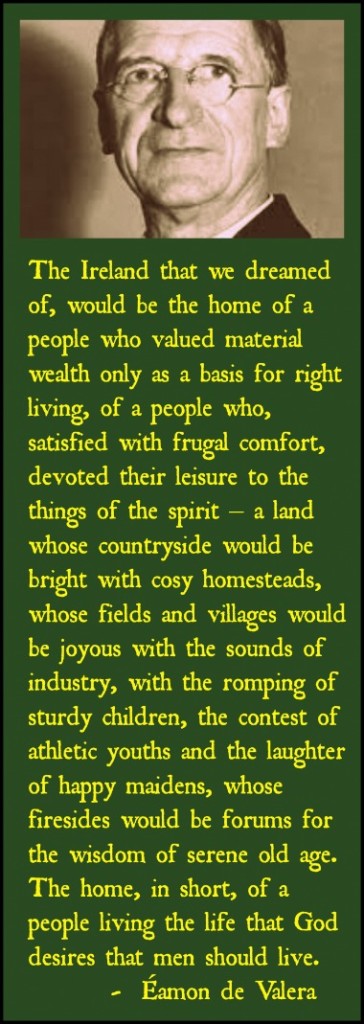

Six years after drafting the above, Éamon de Valera gave a famous speech, outlining the vision of Ireland, which animated him long before the 1916 Rising:

The ideal Ireland that we would have, the Ireland that we dreamed of, would be the home of a people who valued material wealth only as a basis for right living, of a people who, satisfied with frugal comfort, devoted their leisure to the things of the spirit—a land whose countryside would be bright with cosy homesteads, whose fields and villages would be joyous with the sounds of industry, with the romping of sturdy children, the contest of athletic youths and the laughter of happy maidens, whose firesides would be forums for the wisdom of serene old age. The home, in short, of a people living the life that God desires that men should live.

With the tidings that make such an Ireland possible, St. Patrick came to our ancestors fifteen hundred years ago promising happiness here no less than happiness hereafter. It was the pursuit of such an Ireland that later made our country worthy to be called the island of saints and scholars. It was the idea of such an Ireland – happy, vigorous, spiritual – that fired the imagination of our poets; that made successive generations of patriotic men give their lives to win religious and political liberty; and that will urge men in our own and future generations to die, if need be, so that these liberties may be preserved.

What can I say? It is impossible to imagine any politician being elected today on a platform for a life of the spirit “satisfied with frugal comfort!” Yet Catholic Ireland repeatedly re-elected the man: He spent thirty-four years as either prime minister or president of the country.

Thus, for decades, Ireland swam against the tide of English-speaking culture elsewhere. All this started to unravel by the late 1960s. Obviously, increasingly globalised media and the sweeping cultural changes elsewhere in the West played a part.

Personally, however, I do not believe the great transformation in the Catholic Church during the 1960s can be exonerated here.

What would have happened in Ireland, had the Church retained reverence in her liturgy and staunch adherence to devotions like the Sacred Heart, benediction, Corpus Christi processions, holy water in the home, etc.? It is a question well-worth pondering. (Especially as—I increasingly suspect—the old liturgy strengthened the clergy in a manner the new does not.)

At any rate, despite immense cultural and ecclesiastical changes worldwide, Ireland remained, initially, a place apart. How much that is so can be glimpsed from a 1974 survey, which found over ninety percent of Catholics still attended Mass weekly and nearly forty-seven percent went to confession once a month, whereas ninety-seven percent prayed daily. Seventy-five percent put up holy pictures or statues in their homes. Moreover, around a quarter of the population went to Mass more than once a week and a similar proportion confessed once a week or more!

Today, however, all is “changed, changed utterly” in Ireland—to borrow Yeats’ famous refrain regarding 1916. Ireland has largely, if not completely, succumbed to the materialistic values that the 1916 revolutionaries fought to preserve her from. For, as Desmond Ryan writes, Patrick Pearse was concerned that:

The [Irish] people had lost their souls and were being vulgarized, commercialized, anxious only to imitate the material prosperity of England.3

Pearse was hardly alone in this. Much of the Rising’s impetus stemmed from the rebels’ belief that, without it, the soul of Ireland would slowly be extinguished by British governance, British capitalism and British education.

End of two extracts from the introduction.

Once, again, I would emphasise that although the book is very much concerned with Ireland, there are other important themes. Some of these have been featured in other extracts at this weblog and I thought I would list them with links.

On Secularism

Secularism is the Air that we Breathe (here).

On the New Age movement

The Gentle Traditionalist meets the Man with No Name (here).

On the 1960s

The Gentle Traditionalist and the Superiority Complex of the 1960s (here).

On the Key to the Entire book

The following extract probably speaks to the ESSENCE of my book more than anything else:

Famished for Christendom (here).

And we will be featuring further extracts soon.

More details and indeed other extracts can also be found in this archive of posts for The Gentle Traditionalist (here).

Foreword for Monarchy by Roger Buck

1 R. F. Forster, Modern Ireland, 1600-1972 (London: Penguin Books, 1989) 479

2 Tom Inglis, Moral Monopoly, (Dublin: University College Dublin Press, 1998 ) 17, 29

3 Desmond Ryan, Remembering Sion: A Chronicle of Storm and Quiet (London: Arthur Barker, 1934) 161

1‘Zip codes, TV shows and brunch – Ireland is a land of copycats’ http:// www.irishcentral.com/news/irishvoice/Zip-codes-TV-shows-and-brunch—Ireland-is-a- land-of-copycats.html. Accessed July 28th 2015.

Buying Books at Amazon Through These Links Gives Us a Commission. This Supports Our Apostolate. Thank You if You Can Help Us Like This!

Comments

comments are currently closed

2 responses to “English Blood, Irish Heart: A Valentine for Catholic Ireland”

Love this post. I strongly relate. I am only 1/4 Irish but have felt very Irish all my life: perhaps because I am named after my great uncle Patrick; perhaps because I have had a burning desire for liberty since teenage years; perhaps because my Catholic faith ran deep within me, despite my abandonment of it for 25 years. It all goes together and resides in the heart. Holding close the quoted statement by Eamon de Valera. Blessings!

Patricia, it is very good to have your voice here and your testimony to the same mysterious hold that Irishness seems to have. As I say above, my blood may be only 1/8th Irish (possibly more) but I do understand when you express your heart here. My warm thanks to you for this and also for your support elsewhere. May God bless you abundantly!